Tribal Concerns Grow As Water Levels Drop In The Colorado River Basin

10:09 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Michael Elizabeth Sakas, was originally published on Colorado Public Radio.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Michael Elizabeth Sakas, was originally published on Colorado Public Radio.

Lorenzo Pena pulls off the highway and into a drive-through water distribution center on the Southern Ute Indian Tribe reservation in southwest Colorado. He parks his truck and connects the empty tank it’s hauling to a large hose and thousands of gallons of water quickly rush in.

Pena, who works for the Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s hauled water program, has made this trip countless times to deliver water to tribal members who don’t have clean water piped to their homes from the local utility.

“It’s pretty dry around here,” Pena said. “So if people have wells, they’re real slow or the wells aren’t really producing much water.”

If a family on the reservation doesn’t use well water or lives outside of town, they have to haul water to fill their cistern to flow through their home.

The Colorado River is the lifeblood for the Southern Ute and dozens of federally recognized tribes who have relied on it for drinking water, farming, and supporting hunting and fishing habitats for thousands of years. The river also holds spiritual and cultural significance. Today, 15 percent of Southern Utes living on the reservation in southwest Colorado don’t have running water in their homes at all. That rate is higher for other tribes that rely on the Colorado River, including 40 percent of the Navajo Nation.

Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack piped water services than white households, according to a report from the Water & Tribes Initiative. The data also show Native American households are more likely to lack piped water services than any other racial group. Leaders of tribes who depend on the Colorado River say the century-old agreement on managing a resource vital to 40 million people across the West is a major factor fueling these and other water inequalities.

State water managers and the federal government say they will include tribes in upcoming Colorado River policymaking negotiations for the first time.

Some tribal leaders view those promises as lip service and sent a letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland in November asking for legal changes to ensure tribes are included in the negotiations.

The tribes are a powerful voice to ignore. Collectively, they own rights to about a quarter of the water that flows through the Colorado River — a share that exceeds what some states have and includes legally superior senior water claims. The tribes’ slice of the river is only expected to grow as climate change and demand reduce the amount of water available to states whose newer water rights have less legal authority.

Because of a lack of funding and infrastructure, the tribes aren’t using all of their Colorado River water — but they want to. Like any government in the southwest, tribal nations see water as a cornerstone of growing their communities and local economies while supporting the livelihoods and well-being of their members. Some communities in the West are halting development because they don’t have the water to sustain it.

If tribes were to use the full amount of the Colorado River rights they control, that could mean less water for some states already dealing with first-ever water cuts due to historically low levels in Lakes Powell and Mead.

That uncertainty is one reason some states are hesitant to include tribes in river negotiations, said Becky Mitchell, the director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

In 1922, seven states in the Colorado River basin — Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, California and Nevada — signed an agreement, called the Colorado River Compact, on how to “equitably” divide up the river to speed up development across the West.

The execution of this Congressionally sanctioned deal paved the way for massive federal investment in water infrastructure that has mostly benefited the states. Federally funded dams were built to create Lakes Powell and Mead so the states could manage the river’s flow to help uphold the compact’s rules.

Native Americans weren’t considered U.S. citizens when the Colorado River agreement was signed. Tribes were excluded from this agreement and had no direct say in how the water they relied on for millennia was divided — a racial injustice tribal leaders say continues to hurt their members.

The agreement left unsettled how much water tribes could take from the Colorado River, and many tribes throughout the river’s basin are still fighting to resolve this issue today. The U.S. Supreme Court provided some clarification in the 1960s when it adopted a standard that reservations are entitled to as much land as they could irrigate. Before this, tribal water rights were largely ignored, as Lakes Powell and Mead filled with water meant for the states to use.

The situation has blocked tribal governments from accessing federal funding to build their own reservoirs, pipes and treatment facilities to direct clean water to their citizens.

The Colorado River is drying up from climate change and the growing demand on a river system that was over-allocated from the start. Drought conditions forced states to negotiate a new set of Colorado River rules in 2007. The 30 federally recognized tribes in the basin were also excluded from this process.

Those drought rules are set to expire, so the states need to agree on a new way to best manage the river by the year 2026. The tribes, now recognized as sovereign governments, are calling for equal power in the upcoming policymaking process — the results of which will shape how the river is managed for years.

So far, the tribes only have promises that they’ll be included. That’s not enough for many tribal leaders who want a legally granted seat at the negotiating table.

In the letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a coalition of 20 tribes said that their involvement in ongoing decisions about the Colorado River is necessary due to the effects of the decades-long drought. The letter calls for the U.S. government to ensure that the tribes are included in developing and carrying out the policies and rules that govern how the Colorado River is managed. And tribes want the next framework to “recognize and include support for tribal access to clean water.”

Pena has delivered water on the reservation for a few years. He said he was fortunate to grow up with a well, so his family didn’t have to haul water. Other people in the community can’t afford delivery and have to drive miles with their own trucks and water tanks to get what they need.

If the weather is bad, or a truck breaks down or the supply runs out before a family can make another trip, families might go days without clean water. Without a reliable and easily accessible clean water supply, these households struggle to shower, clean their homes or prepare healthy food.

Lorelei Cloud, a member of the Southern Ute Tribal Council and a leader of the Water and Tribes Initiative, grew up on the reservation in a home without running water. At an October law conference at the University of Colorado Boulder, Cloud shared her family’s experience of filling up water tanks at her uncle’s home with his garden hose. Cloud’s family had to ration their supply to ensure it lasted the whole week.

“A few times, it didn’t last for that week. And we actually got water from the irrigation ditch in front of the house, boiled that and we used that,” Cloud told conference attendees while tearing up.

When she was 12, Cloud moved to a new home that did have running water, but it was contaminated with methane, which can occur naturally or enter a well from nearby oil and gas development.

“It wasn’t just in the water, but it made the whole house smell like methane. And that ended up becoming a normal part of our life,” she said. Cloud’s son still lives in that home and he recently ran out of water. It’s unclear whether the well dried up or the pump stopped working, but Cloud said her son has had to take showers at her home while they figure out the problem.

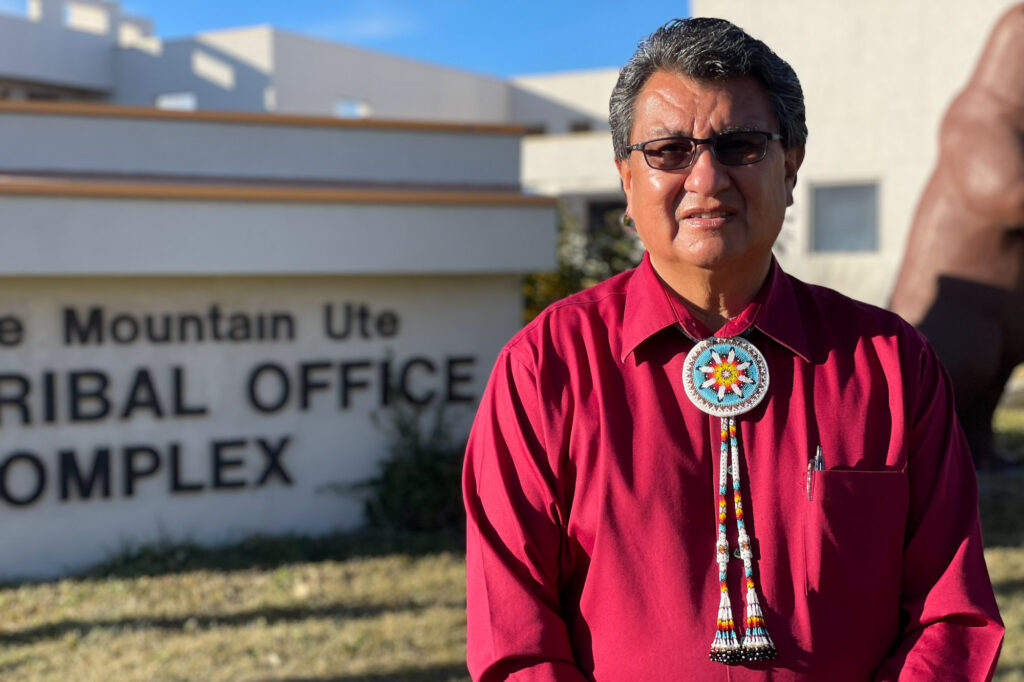

Manuel Heart, Chairman of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe in southwest Colorado, said excluding tribes from helping create and update the river’s regulations is another example of the U.S. government marginalizing native voices.

Heart said the federal government and states need to apply the government-to-government tribal consultation policy to river negotiations since those actions and decisions will have a substantial and direct effect on tribes.

“Everybody is growing, population-wise. And their needs are growing,” Heart said. “You’ve got to include tribes in that too, because they too are part of that equation.”

Heart said these consultations could lead to other solutions to better manage water in the Colorado River. One possibility is where tribes sell leases for farm irrigation water to increase reservoir levels and use the proceeds to help pay for the operation and maintenance of aging water infrastructure. One of the most significant issues on the Ute Mountain Ute reservation is the cast iron and clay pipes installed in the 1950s that are clogged with sediment and tree roots, Heart said.

Homes in the town of Towaoc on the reservation didn’t get indoor plumbing until the 1980s. Heart remembers his family driving 15 miles to Cortez to do laundry and take showers when he was younger.

Desperate to get water to the town, the tribe negotiated with the federal government. The Ute Mountain Utes gave up senior water rights dating back to 1868 for funding to build McPhee Reservoir. It’s filled with 1988 junior water rights, which are susceptible to cuts during drought. Heart feels the deal was wrong.

“We just got backed into a corner, take it or leave it,” Heart said.

It’s difficult to know what might have happened over the last 100 years if the tribes were included in the negotiations of the 1922 compact. Heart believes the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe wouldn’t have been in a position where it needed to give up valuable water rights for access to clean water.

With the worsening decades-long megadrought, the water supply in McPhee Reservoir is dropping. Heart said the tribe is only getting about 10 percent of their share of water, which has cut into farming revenue needed to pay for the operation and maintenance costs of the reservoir itself.

Looking out his office window, Heart reflected on the lack of snow. Much of the reservation is in extreme drought. “It feels like summer here, and we’re in November. If I remember, when I was a child, we already had snow on the ground.”

Heart said one way to make tribal voices official in river negotiations would be to appoint a tribal representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission, which was created through Congress and includes water officials from Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico. Heart said federal legislation is needed to amend that to include a spot for the tribes.

Heart is hopeful that representation in the negotiations will mean that all tribes in the basin will finally have their water rights quantified. Some tribes, like the Navajo Nation and Hopi Tribe, still don’t know just how much water they can use because of the way the U.S. government sets aside water for each individual reservation. Many of these water rights date back to when the reservation was established and pre-date the Colorado River agreement, giving them a valuable legal distinction because they cannot be curtailed during a drought.

According to a policy brief from the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment at CU Boulder, 22 of the 30 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin collectively own the rights to use around 25 percent of the Colorado River’s annual flow. Twelve other tribes still have unresolved claims, which will likely increase the amount of water tribes can use as those rights are settled.

Despite holding legal rights to a quarter of the water in the Colorado River, tribes can’t use their full share due largely to a lack of funding and water infrastructure. As tribes work to develop and use their water rights fully, states are concerned it will mean less water for their use.

“Because tribal water rights tend to be senior, they’re going to slot into the system and kind of bump back a whole bunch of existing water rights that are being used,” said Anne Castle, a senior fellow at the Getches-Wilkinson Center and the former assistant secretary for Water and Science at the U.S. Department of the Interior. “Those water rights will lose priority.”

Castle said determining how much water tribes control is crucial for the tribes and provides certainty for all water users in the system. Including tribes in river-management discussions would also help tribes prioritize spending $3 billion in funding from the bipartisan infrastructure bill earmarked for water projects, she said.

Castle said that the law of the river hasn’t historically dealt with things like access to clean drinking water. Including Tribal representation could change the tenor of the overall discussion and “expand the universe of issues that need to be dealt with,” she said.

“When you bring tribal interests to the table, then those issues are elevated and become a part of the discussion. Because that’s obviously a critical consideration for many of the tribes along the river,” Castle said.

Studies show a higher infection rate in communities with limited access to running water, which disproportionately affects tribal communities, said Bidtah Becker, a member of the Navajo Nation and an associate attorney for the tribe’s utility authority who worked on a clean water report for the Water and Tribes Initiative.

“It just felt like this is the moment to shine a light on this issue,” she said. “It just seemed that the collective response was so different than it had been in the past.”

One of the ways tribes have funded water projects is through money from legal settlements with states and the federal government over their water claims, which can take decades to finalize. It took more than 30 years for the Navajo Nation to settle some of its water rights. Becker said people often ask about the connection between water rights and water development.

“They’re interconnected, because you need funding to develop your water rights. But if you don’t have a fully resolved water right, it can be challenging to get funding [to develop it],” Becker said. The Navajo Nation still has unresolved water rights.

Becker was surprised that the infrastructure bill included funding for tribal water projects — enough, she said, to fund an entire backlog of water projects that has been growing since the 1980s. The money could mean tribes don’t have to wait for settlements to fund infrastructure projects to put their water rights to better use.

The lack of clean water access for tribes is rarely discussed because it’s a “dignity issue,” Becker said. “It’s embarrassing to say, ‘I can’t get up and shower in the morning.’” That’s especially true for younger tribal members who go to school with flushable toilets and spend time with students who smell like soap and shampoo, she said.

“If [this funding is implemented effectively], we could have a whole generation of Indian folks who are not going to have the disadvantages that their parents had. Or even their older brother or sister,” Becker said.

Becker acknowledges that it can be “technically challenging” to figure out how clean drinking water fits into Colorado River negotiations. Still, she said equity needs to be considered in “everything we do.”

She said since the river agreement was signed before many Native Americans had the right to vote, the states and the federal government are still grappling with the concept of, “Who are the tribes?”

“What are tribal people? How do they fit into our system or not? I think they were unresolved then, and I think that’s what we’re still trying to resolve to this day,” Becker said.

Daryl Vigil, a member of the Jicarilla Apache Nation and the tribe’s water administrator, said the tribe was living off government-issued rations on a reservation that wasn’t their traditional homeland when the Colorado River Compact was signed, a decade and a half before the tribe even organized as a formal government and adopted its constitution.

Vigil said a hundred years of Colorado River policy were built before tribes could even get into the mix of the conversation.

He said it was a “call to arms” in 2012 when the Department of the Interior released a study that left out tribes in a calculation of water supplies and demands in the basin. Tribes pushed for an additional study, which resulted in the 2018 Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study Report. It recognizes the large portion of Colorado River Rights the tribes hold and the potential effects on the river system if tribes start to use these rights in full.

Since the tribes are sovereign governments, Vigil said they should be invited to a “sovereign table that doesn’t exist” to discuss how the Colorado River is managed. He said instead, the fallback is that states or the federal government act as a trustee to represent and protect tribal water interests, which “just hasn’t happened historically.”

The tribes have been told they will be included in the upcoming negotiations, which are likely to happen over the next two years. However, Vigil said it’s lip service until the federal government fulfills its promise to engage tribes as equals to the states on Colorado River management decisions.

“Anything that goes on right now in terms of commitments, promises, whatever you want to call it, is kind of meaningless because it’s not backed up by the existing law and policy,” Vigil said. Until new policies are put in place or the law is changed, Vigil continued, there is nothing to ensure the tribes are included.

It’s unclear what tribal participation might look like. Becky Mitchell, the director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, said states should have a “back and forth” discussion instead of dictating terms. Mitchell is involved in the clean water for tribes initiative and said her office has started working with the tribes on Colorado River issues leading up to the next round of formal negotiations. Mitchell urged her counterparts in other states to do the same.

“I think it’s incredibly important when we talk about trust in government, that we have to be open to different ways to do things than we have before,” Mitchell said. “We have to figure out, how do we create a more certain future for everyone in the basin?”

This piece is part of a collaboration that includes the Institute for Nonprofit News (INN), California Health Report, Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism, Circle of Blue, Colorado Public Radio, Columbia Insight, The Counter, High Country News, New Mexico In Depth and SJV Water. The project was made possible by a grant from the Water Foundation with additional support from INN. For earlier stories in the Tapped Out series, click here. The Western Colorado Community Foundation provided additional support to CPR News.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Michael Elizabeth Sakas is a climate/environment reporter for Colorado Public Radio. You can learn more about CPR’s climate coverage by signing up for their newsletter.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. And now it’s time to check in on the State of Science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News–

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio–

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. If you live out west, water has probably been on your mind a lot over the last few years. States have had to deal with drought conditions. And a world where there’s not enough water to go around seems to be getting more real every day. If you’re part of a western tribal nation, the issue of water access is even more dire.

That’s because Indigenous peoples have long been left out of conversations about how to divvy up resources. In the Colorado River basin, leaders from 20 tribal nations are now asking the federal government for a seat at the table. Joining me today to break down the complications of water rights in the west is my guest Michael Elizabeth Sakas, climate and environment reporter for Colorado Public Radio, based in Denver. Welcome to Science Friday.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s start with a little context, if you will. Who are the players that get their water from the Colorado River basin?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: The Colorado River starts in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. And it flows through the southwest until it reaches Mexico. And along the way, seven states and 30 federally recognized tribes use this water for ranching and recreation, and of course, drinking water. And even cities outside of the Colorado River basin, like Denver and Los Angeles, rely on this water, which, in total, supplies around 40 million people. It also provides electricity for the west through the turbines that spin at hydroelectric dams along the river.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so people really are dependent on the river. Tell us what the state of the river is now.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: What’s happening in the basin is quite alarming. The two largest reservoirs in the United States are Lake Powell and Lake Mead. They’re both filled with Colorado River water, and they both hit their lowest levels on record this year. The water levels dropped so low, the federal government declared the first ever shortage on the Colorado River in 2021, which means cuts to some water users next year. The average flow of the Colorado River has dropped about 20% since the 1900s. And roughly half of that decline is due to climate change. And these hotter temps have helped fuel a 20-year megadrought across the west. A megadrought is essentially a drought that can last decades.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: And this rapid decline in the river could soon cause problems between the states that share this water.

IRA FLATOW: Now wasn’t there an agreement almost 100 years ago from managing the water that was created? I mean, what does this agreement say? And is it still relevant?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Yeah, the agreement is called the Colorado River Compact. And it essentially divided up the water in the river. So each state knew how much water it could use to fuel their growth and development. The states in the upper part of the basin get this much, and the states in the lower part of the basin get this much. And the agreement says those upper basin states have to keep a certain amount of water in the river so it can flow to those downstream states.

IRA FLATOW: But of course, this was crafted long before droughts caused by climate change was the reality, right?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Yeah, right. When this compact was signed 100 years ago, the states didn’t consider that the climate could change and that the river would dry up as much as it has. And when the states divided up this water, they didn’t use percentages. They actually used fixed numbers on how much water each state could use. I spoke with Brad Udall, a water and climate scientist with Colorado State University. And he said that’s what might soon cause the issues between the states.

BRAD UDALL: The fatal flaw of the compact as currently written are these fixed numbers in there. You can’t have fixed numbers in a declining system. That’s going to unduly impose pain on a party that’s completely undeserving and never signed up for that.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Because the river has dried up so much, there’s a chance that part of that 100-year-old agreement between the states could be broken soon. Because it might mean the states in the upper part of the Colorado River basin can no longer send down the amount of water to the lower basin states as agreed to in the compact. That could lead to court battles between states and some water users being cut off from the river.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking about broken agreements, let’s talk about the Indigenous tribes from the very beginning. Were they included in this agreement?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: No, when the compact was signed, the 30 tribes in the basin were not included in the agreement. And tribal leaders say the legacy of that racial injustice continues to hurt their members today. Bidtah Becker is a member of the Navajo Nation and an associate attorney for the tribe’s utility.

BIDTAH BECKER: Tribal people living on reservations didn’t even get the right to vote in Arizona until 1948, a whole generation or two after the compact was signed. So even this concept of who are tribes, what are tribal people, how do they fit into our system, I think they were unresolved then. And I think that’s what we’re still trying to resolve to this day.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Since the compact was signed, states have had to renegotiate how to better manage the Colorado River in a drier reality. And the tribes have been excluded from those river negotiations as well.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of the tribes, I know there’s also this additional layer of American Indian treaty rights. What do treaty rights say about how much water from the Colorado River basin should go to tribes?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: It wasn’t until the early 1900s that the US Supreme Court recognized that tribes in the Colorado River basin had reserved water rights. Essentially, that meant that these tribes had the right to use Colorado River water to meet the needs of their reservation. But how much water is that? That wasn’t clarified until the 1960s, when the Supreme Court adopted a standard that said tribes get as much water as they would need to irrigate their land.

By this point, Lakes Powell and Mead are built, and they’re filling with water for the states to use. And the tribes are going to court to figure out how much of that water is theirs. Now, at this point, it’s estimated that the tribes hold rights to use a 1/4 of what flows through the Colorado River. That’s more than what Arizona gets. And this amount is only expected to grow as more tribes figure out how much water is theirs to use.

IRA FLATOW: And what are the tribes then asking for right now, as the water situation gets more dire?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Because the river is drying up, the states have to renegotiate how to manage the river in a new climate. Those new rules have to be adopted by 2026. So the negotiating of those rules have unofficially already started and are expected to officially start soon. And the tribes want to be included in this process, recognized as sovereign governments and as equals to the states. Lorelei Cloud is a member of the Southern Ute Tribal Council and a leader of the Water and Tribes Initiative. Here she is speaking at a recent event at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

LORELEI CLOUD: We’ve been stewards of this water for such a long time. And we need to make sure that we’re always in the conversations of how much water that we are using to make sure that we all can have sustainable water.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Cloud grew up on the southern reservation in Southwest Colorado with no running water. Native American households are more likely to lack piped water services than any other racial group. So a big part of why the tribes want this formal seat at the negotiation table on Colorado River policy is to make changes that can mean clean water for their members.

IRA FLATOW: There really is an interesting new wrinkle now. And by that, I mean that for the first time, the US has a Native American Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland. Did the tribal members you talk to say if this changes anything?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Yeah, I spoke with Manuel Hardt, the chairman of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe in the Four Corners region.

MANUEL HARDT: We have Secretary Haaland, who’s a Native American from the Pueblo tribe. And she understands the region here. She comes from this region. So she knows what we’re feeling and what we’re going through. So that is a plus on our side.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Hardt said he feels an overall shift, that the states and the federal government are listening to tribes more now on the issue of water. The states have said tribes will be included in the upcoming negotiations, but promises aren’t enough for these tribes. They want to see legal change from the federal government to ensure their inclusion.

IRA FLATOW: OK, so let’s play, what if a formal shortage is declared? What’s the plan? I mean, is there one?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: It’s unclear what those states in the upper Colorado River basin will do if they aren’t able to send enough water to the downstream states. And that’s a big problem because Brad Udall, the water and climate scientist, says there’s a chance the Colorado River system could reach that crossroads in the next five years with the way things are going with the hydrology.

BRAD UDALL: That will be a day of reckoning for the upper basin. And frankly, I think you probably never, ever want to get there. You want to cut demands or have an agreement, or somehow, not get into a violation of that, where all of a sudden, all bets are off on how it gets resolved.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: What could happen is the newest water users with water rights that are less senior could be cut off from the river, or all water users are cut back in equal amount so more water can flow downstream. But a formal shortage might never happen. The upper basin states could possibly successfully argue in court that they’re not at fault for the drop in the river, that it’s climate change, not overdevelopment or anything like that.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting argument. I mean, are there any Colorado River management negotiations on the calendar right now? Or are we in a wait and see moment?

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Informal negotiations have already started between states and water commissioners, but formal negotiations don’t have a set start date just yet.

IRA FLATOW: That’s really interesting. Thank you for taking the time to be with us today.

MICHAEL ELIZABETH SAKAS: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Michael Elizabeth Sakas, climate and environment reporter for Colorado Public Radio based in Denver. Michael’s reporting on this was part of a collaboration with the Institute for Nonprofit News on Power, Justice, and Water in the West. And we’ll be talking a lot about water in 2022, so we want to hear from you, our listeners. What are your biggest concerns about water for our warming planet? Are you pessimistic? Is there technology you’re hopeful about? We want to hear about it. Let us know on our SciFri VoxPop app, and you can get that wherever you get your apps.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.