Closing Out The Cephalo-Party

23:47 minutes

The eight-day squid-and-kin appreciation extravaganza of Cephalopod Week is nearly over, but there’s still plenty to learn and love about these tentacled “aliens” of the deep.

After a rare video sighting of a giant squid—the first in North American waters—last week, NOAA zoologist Mike Vecchione talks about his role identifying the squid from a mere 25 seconds of video, and why ocean exploration is the best way to learn about the behavior and ecology of deep-sea cephalopods.

Then, Marine Biological Laboratory scientist Carrie Albertin gives Ira a tour of the complex genomes of octopuses, and how understanding cephalopod genetics could lead to greater insights into human health.

Finally, SciFri digital producer Lauren Young wraps up Cephalopod Week for 2019. See how you got down and squiddy with it below!

Vampire squid. Chambered nautilus. Mourning cuttlefish. We asked you to call in with the best cephalopods in the sea, and you definitely delivered! Listen below to these ceph-heads vouch for their favorites.

Beth P., Vermont

My favorite cephalopod is the nautilus. I live in Vermont and I give tours at the State House, and on the floor of the State House lobby in the black marble is a fabulous fossil of a chambered nautilus. On tours we call him the “permanent resident of the State House.”

Justin, Syracuse, New York

My favorite cephalopod is the cuttlefish, just because I like to cuddle.

Chase W. Jr., Pennsylvania

My favorite cephalopod is the Vampire squid scientifically named Vampyroteuthis infernalis. The reasons I like it is because it has a very cool name and it’s different from most other cephalopods by having webbed arms/tentacles, thorns on their arms, and they shoot viscous fluid instead of ink and they have some bioluminescent parts on their head.

Leigh M., Lee Summit, Missouri

My favorite cephalopod is any octopus because of how smart and unique they are.

Tom B.

Here is my favorite cephalopod. It’s name is Hawaiian bobtail squid. This guy is just about over one inches in length and it lives in Hawaii in coastal shallow waters…. Hawaiian bobtail squid acquires a bacteria known as Vibrio fischeri, this is a bioluminescent bacteria. During nighttime it becomes bioluminescent, and it starts to shine under the squid, which illuminates the squid’s shadow created by the moonlight. So this makes bobtail squid invisible to predators, and I think this is an awesome relationship between this little tiny squid and the bacteria, Vibrio fischeri. (See squid biologist Sarah McAnulty catching bobtail squid for her research in Hawaii on an Atlas Obscura trip!)

David T.

My favorite cephalopod has to be the Mourning cuttlefish, or the two-faced cuttlefish. They’re so awesome because during mating season, while the big males are fighting with each other, the smaller males can’t compete with the large males so they will disguise themselves as females, swim past the fighting males, and then sit next to the females. So when the females look at them they see that their male, but when the males look back, they’ll see that this disguised cuttlefish looks still like a female.

Transcripts and audio were shortened for length.

You showed off your top-notch fashion, asked scientists your curiosities, played ocean-themed games, and met up with your fellow cephalo-pals.

Cephalopod night was a blast with @scifri! #CephalopodWeek pic.twitter.com/0sWV2To5Ll

— Bridget Garraway (@bridgetgarraway) June 27, 2019

IT WAS NOT JUST FOR CHILDREN!! Thanks @scifri !! And I dressed for the occasion, obviously ? ? pic.twitter.com/MUFLJJpbkF

— Hannah Wirtshafter ? (@AheadOfTheNerve) June 25, 2019

The cephalopodophiles are out in force at @scifri @atlasobscura Ceph Movie night. @pilesofsquid is skyping in and dropping great ? insights. pic.twitter.com/xmxeKhJzwZ

— Erin Chapman (@elcwt) June 22, 2019

Yesterday was Cephalopod Movie Night with @scifri and @atlasobscura and we had silhouette artist Nina Nightingale there cutting out people’s silhouettes and adding tentacles in 90 seconds or less! So, here is me as Grandmother Cthulhu. pic.twitter.com/FmCrZ8jhxM

— Leyla I. Royale (@leylairoyale) June 28, 2019

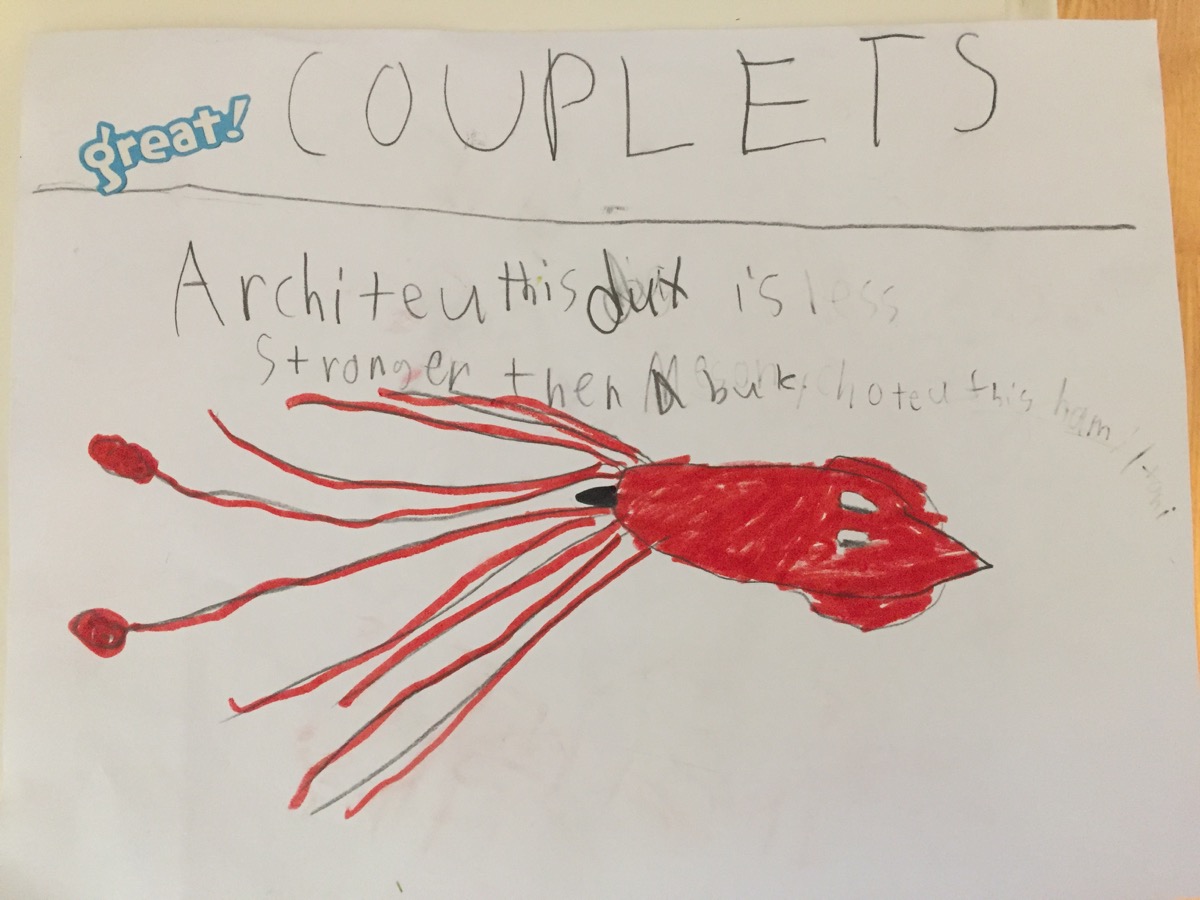

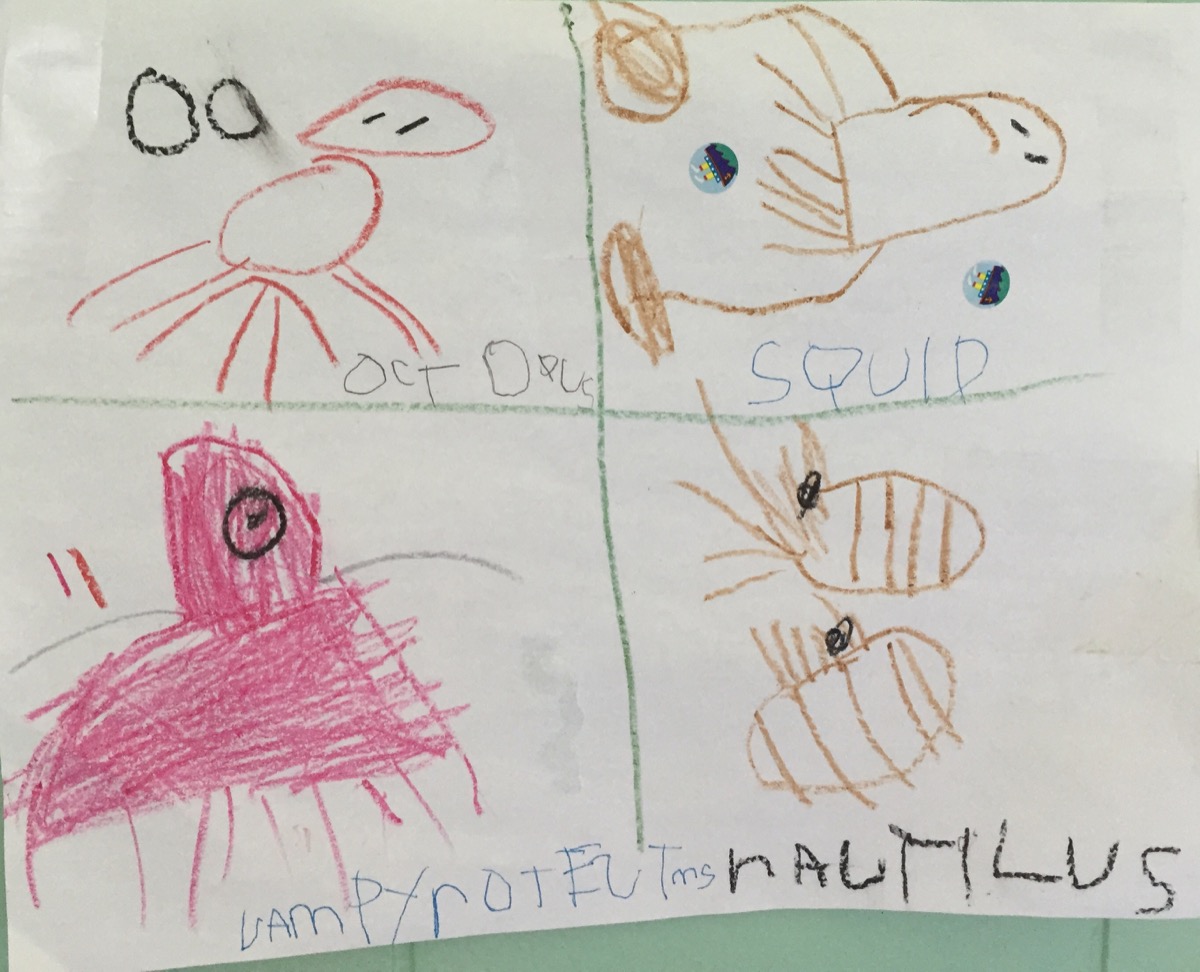

You got really creative for this year’s Cephalopod Week, from origami to poetry to illustrations.

“Octopus, Octopus,” recited by 6-year-old Gwendy G., Denver, Colorado.

Octopus, octopus

Just like a jelly

Octopus, octopus

Its big fat belly

Octopus, octopus

It moves like jelly

Octopus, octopus

Low ho hellie

Happy little octopus wishing all a great Throwback Thursday of Cephalopod Week. An octagon based origami model. Foil paper.#CephalopodWeek #STEM #STEAM#ThrowbackThursday #SquidSquad#origami #BritishOrigami @scifri @BritishOrigami pic.twitter.com/jz3I9Ni8bR

— Kristopher Schwinn (@KitSchwinn) June 27, 2019

And another cephalo-fan artwork for #CephalopodWeek pic.twitter.com/JaBFbRenua

— Olivia V. Ambrogio (@Squidfan) June 25, 2019

Another for #cephalopodweek, the nautilus! A perpetual favorite — quite literally, as they’ve been around for a bajillion years. I believe that’s the technical term. pic.twitter.com/7RY3Hx7bZt

— Skylaar Amann | Illustrator (@SkylaarA) June 23, 2019

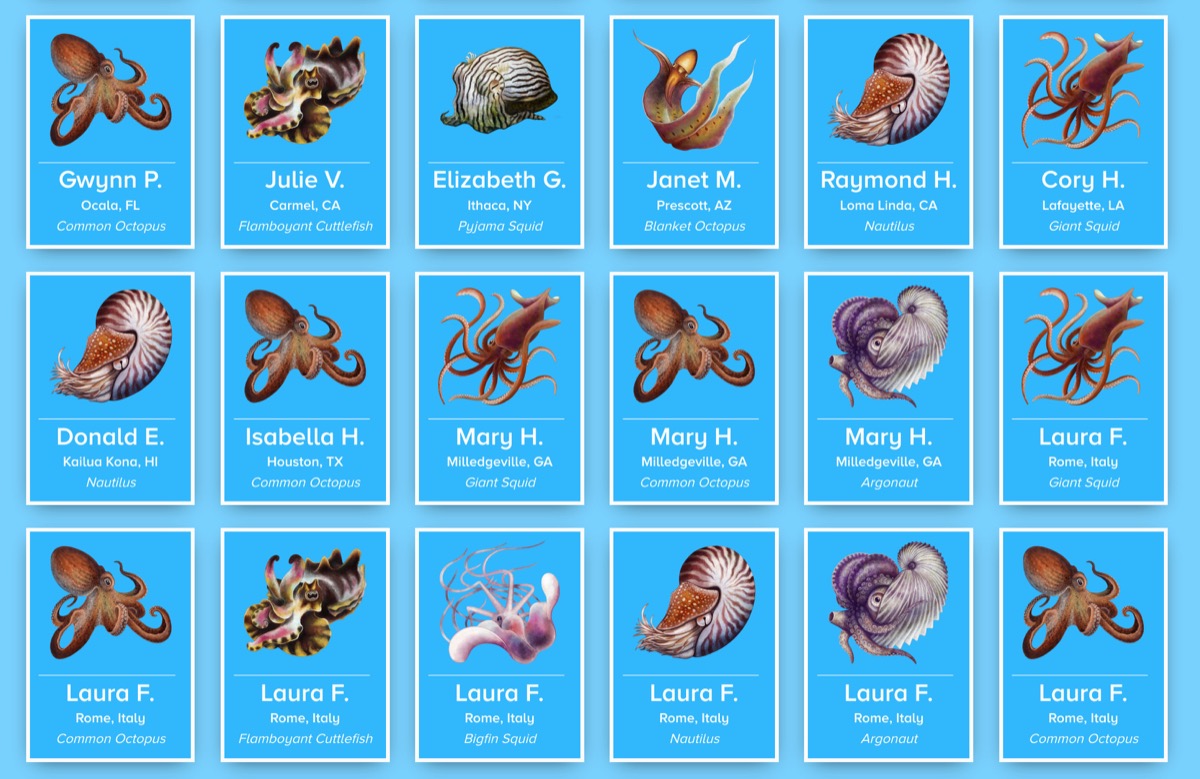

From the many majestic common octopuses to the dozens of dazzling flamboyant cuttlefish, the illustrated cephalopods you sponsored in our Sea of Support made it shine brighter than a glowing bobtail squid. You made our Sea of Support feel like an ocean of cephalo-love. Thank you!

Till next year, cephalopod champions! Thanks for joining in on all the fun!

With every donation of $8 (for every day of Cephalopod Week), you can sponsor a different illustrated cephalopod. The cephalopod badge along with your first name and city will be a part of our Sea of Supporters!

Michael Vecchione is a zoologist in the NOAA Systematics Lab at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Carrie Albertin is a cephalopod researcher and a Hibbitt Early Career Fellow at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

IRA FLATOW: Bobtail squid on the brain? Mimic octopus on your mind? If you feel like you’re knee deep in Nautiluses, then chances are you’ve been playing along with Cephalopod Week for the last eight days, like our listener Gwendi.

GWENDI: Octopus, octopus, just like a jelly. Octopus, octopus, it’s big, fat belly.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, we’ve been celebrating our suckered friends here at SciFri with live events, haiku, and lots and lots of ceph science. In fact, just as we are kicking off the cephalobration last week, The New York Times reported on a stunning finding, a new video of a giant squid for the first time in North American waters and only the third ever video taken of the elusive creature. Here to talk about the squid sighting is Dr. Mike Vecchione, a zoologist for NOAA’s Systematics Lab at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. He helped the research team identify the giant squid. Welcome to Science Friday.

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Good afternoon, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Good afternoon to you. So what’s the story with this squid sighting? How did these researchers find it?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Well, first of all, the credit goes to the people out on the ship. And one of them was Edie Widder. She has developed a tool to use in the deep sea that she refers to as a Medusa.

And it’s a kind of low-light camera that’s in a housing that’s very quiet. It uses red light instead of white light and uses a lure that looks like a jellyfish that’s lighting up with bioluminescence. So this is a new kind of technology that she invented. And it’s the same thing that she used in Japan when she got the first-ever video of a giant squid.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so she developed a new kind of lure with lots of lights on it. If sightings these animals on video is so rare, how do we know anything about them?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Well, we’ve known about them for a long time. Because for one thing, we used to kill a lot of sperm whales. And sperm whales eat giant squids. And so when they were being butchered, the stomachs were opened up. And we found giant squids in the stomachs of sperm whales.

Also, sometimes we find them floating dead at the surface. And sometimes they wash ashore on to beaches. And now as we’ve fished out the commercial fisheries closer to shore, and commercial fisheries have moved out into deeper and deeper water, they’ve caught more and more giant squids, as well. So we’re learning about them from the dead specimens that are caught by commercial boats and also the ones that are washed up on the shore.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I’m Ira Flatow talking with Dr. Michael Vecchione, a zoologist at the Smithsonian. So how excited are scientists like you about seeing a very rare sighting of a live giant squid?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Well, I’m excited about it. Because like I said, all the information we had previous to these videos was from dead specimens. So we knew about their anatomy, and some idea of where they lived, and stuff like that. But we have no idea how they make a living down where they actually are found.

IRA FLATOW: Do you find that the giant squid– it certainly has the public’s attention because of the movies. And they have seen stories about them. Is it your favorite? Or do you have a different favorite?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Well, my favorite is any weird squid from the deep sea. I do a lot of deep sea biology. And we know so little about the deep sea, which is the largest living space on our planet, that we find strange things very regularly. And every time we come across something new, it’s exciting.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. What is your favorite find in the ocean so far?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Well, usually it’s the most recent one that I’ve come across. So just as an example, I think it was last year that NOAA was exploring with an ROV, Remotely Operated Vehicle, or a robot submarine. And they came across a squid that, when we saw it on the screen, nobody even knew what kind of animal it was, much less what species of squid it was. It wound up being called a twisted squid.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: So that was the most recent one. But a couple of other examples include the Casper octopus, which made a big splash in the news a few years ago, and the Bigfin squid or a long-arm squid, which was discovered in the last decade.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Tell me, if you could fulfill a dream, what would be the perfect video clip that you would like to see?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: [LAUGHING]

I’m not sure I can answer that. We keep finding things that are totally unexpected. And every time we find unexpected things, it just blows me away. So I’m not sure I can tell you what the perfect one would be, because we haven’t seen it yet.

IRA FLATOW: So wait a minute. So do you think there is another squid out there waiting to be discovered that we haven’t seen yet?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: I absolutely know it. In fact, using the same device that Edie developed when she was first working on it and she set it out for one of its first deployments, as soon as she turned it on, she got videos of a big squid. It was 2 meters long. And I couldn’t figure out what it was.

And I sent it around to my friends who work on this kind of thing. And none of us could figure out what it was. And I would love to get more video of that and maybe a specimen or more information that would let us figure out what kind of squid that was.

IRA FLATOW: You sound like you have discovered these Sasquatch of squid here.

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: [LAUGHING]

None of them have very big feet.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHING]

But we don’t usually think that there are these undiscovered things. But yeah, it seems like there are. And that’s what makes this exciting and wonderful, isn’t it?

DR. MIKE VECCHIONE: Yeah, in the deep sea, there are a lot of undiscovered things.

IRA FLATOW: All right, thank you very much, Dr. Vecchione, for taking time to be with us today– Mike Vecchione, a zoologist for NOAA’s Systematic Lab at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. He helped the research that identified the giant squid.

We’re going to take a break. And we’re going to deep dive back into cephalopod genetics and why some researchers want to help cephalopods become the next lab rats for human disease. That’s really an interesting development. And we’ll talk about it.

As we wrap up Cephalopod Week– our number 844-724-8255, if you’d like to tell us– 844-724-8255. We’ll be right back after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We came, we saw, we cephed. And now we’re putting Cephalopod Week 2019 to bed. And you know one thing we love to see every year is how much you love cephalopods. Here’s a voicemail from 8-year-old Chase telling us about his favorites favorite cephalopod.

CHASE: My favorite cephalopod is the vampire squid, scientifically named Vampyroteuthis infernalis. The reasons I like is because it has a very cool name. And it’s different from most other cephalopods by having webbed arms/tentacles and thorns on their arms. And they shoot viscous fluid instead of ink. And they have some bioluminescent parts on their head.

IRA FLATOW: That was great. My next guest is also a big fan. She’s looking at the genomes of these alien-like creatures. She started there with the California two-spotted octopus in 2015 and is continuing to look for patterns in the genes of cephalopods that might explain both their weirdness and their success in surviving their ocean habitats. Dr. Cari Albertin, a cephalopod researcher at the Marine Biological Lab in Woods Hole, welcome to Science Friday.

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Thanks so much, Ira, happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Starting with that first octopus genome back in 2015, what are we finding out about cephalopods from their DNA?

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Well, we’ve uncovered all sorts of things that we didn’t expect to find. So a genome contains all of the information you need to make an animal. And before, we’d been looking for genes that we knew to look for, genes that are available in other animal genomes.

And by sequencing the genome of an octopus, we could find out not only what genes they had that were in common with flies, and mice, and us, but also what genes they have that are completely unique to them. And so that’s uncovering a whole realms of new biology that we didn’t even know to look for before we sequenced it.

IRA FLATOW: We know how smart they are, especially the octopuses. Is there anything in their genes that explains their intelligence or their really complex nervous system?

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Yeah, we went in expecting to find a whole bunch of different kinds of genes in there. And one of the really surprising things we found when we looked in the genome of Octopus bimaculoides is they had a family of genes– these are called protocadherins. And these are genes that help cells stick together.

And up until then, they’d only been found in animals like us with a backbone. And they are important in wiring big, complicated nervous systems like our nervous systems. And so we were really surprised to find them in the octopus genome. Because they’re not available in the normal model organisms that people study, like fruit flies or nematodes, that don’t have backbones. And so this was a complete and utter surprise.

IRA FLATOW: Mm. So they even make the octopus a good area for research, then, to learn about that.

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: Mm. Come on. Fill us in on what else exciting discoveries you have made about it.

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Well, so one of the things that we found were that cephalopods have these really, really large genomes. They’re about the same size as our genome. And so this is a lot bigger than the genomes of fruit flies or nematodes.

So our genome is about 3.2 billion base pairs. And octopus genome is about 2.7 billion. And that’s kind of a hard number to understand. So to put it in perspective, that’s about 1,000 times the number of letters that are in War and Peace, all contained in each and every cell in these animals.

And so they have these big, complicated genomes. But many of the genes that they have in there are shared across different animals. So they’re surprisingly similar to us.

In addition, like I mentioned earlier, they have whole suites of genes that are unique to cephalopods. Some of these genes create the iridescence you see in their skin. And in the last couple of years, we’ve had some more cephalopods genomes come out, including the genome of the Hawaiian bobtail squid.

And we see that squid sometimes have different sets of genes than even octopuses. So in some squids, they have a family of genes, for example, that are on the sucker ring teeth just on the tentacles. So octopuses don’t have tentacles. They have eight arms.

Squid have eight arms plus two tentacles. And these tentacles have specialized ring teeth. And they have this plastic-y kind of feeling to them. And they’re made by a completely novel protein family.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And what about them being smart? Do they have a lot of nervous system genes in them?

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Absolutely. They have similar numbers to the numbers that we have in terms of neuronal genes that are important in axon function. And so, yeah, they are just surprisingly normal from an animal standpoint. And yet, they have all of these fantastic otherworldly abilities.

IRA FLATOW: And I understand that cephalopods can edit their own RNA. Tell me about that, please.

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Yeah, this was another thing that’s been coming out over the last few years. A lot of this work has been done by Josh Rosenthal here at the Marine Biological Laboratory and his collaborator, Eli Eisenberg. And they’re finding that cephalopods are able to edit their mRNA.

So when you turn a gene on, it makes an mRNA copy. And this mRNA copy is then translated into a protein. And that’s how the gene actually goes and functions.

And it turns out that cephalopods are able to go in and change the sequence of their mRNA, potentially changing the sequence of the protein, creating a whole bunch of different proteins from just a single gene. And a lot of animals can edit their RNA. We edit our RNA. But cephalopods are doing it orders of magnitude more than other animals.

So this is really exciting. This is opening up a whole set of questions that are available only in this species. Why are they doing this? How are they doing this? And so we’re getting to some really cool areas of biology in these animals.

IRA FLATOW: Cool is the right word. Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Bill. Hi, welcome to Science Friday.

BILL: Thank you for taking my call. I appreciate it.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

BILL: OK, my question was, in the recent Scientific American, there was an article about cuttlefish having the same type of sleep pattern or a similar sleep pattern to mammals and humans, including perhaps rapid eye movement and maybe dreaming. And given, according this article, that we diverged as a species, as a genus almost 500 million years ago, might that be something in both the genomes that is still tied together?

IRA FLATOW: Hm. Do cephalopods dream, do you think?

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: There’s some really exciting research being done on their behavior. This is outside of the realm of my experience, but I’ve definitely seen them flickering around while they’re sleeping.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let me let me move over to a question you might be able to answer.

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: I was just going to say, the exciting thing is that the complicated nervous systems that we have in animals like us that have backbones and then in cephalopods are thought to be the result of completely separate evolutionary trajectories. So this might be an indication of what you need to have when you have a big brain.

IRA FLATOW: One question– one final one for you. One thing that researchers– and you touched on this before, and I want to delve into this a little bit more– is using cephalopods like lab rats for research that might help us. Why is that such a good idea?

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Well, in part, as I’ve been saying, they have this really cool biology. And we can’t study the rapid camouflage changes in a mouse, because they don’t do it. And so traditionally– 50, 100 years ago– people were studying animals based on their special traits. They have a unique thing that they can do. And so people will go study them.

But in the last 30 or so years, we’ve had this revolution in the ability to have what are called model organisms or lab rats, where you can go in, and you can keep them in the lab. And you can create mutants. You can study their biology at a molecular level.

And this has only been available in a very few number of animals– so like I mentioned, fruit flies, or nematodes, or mice. And in the last couple of decades, the last decade or so, we’ve had this opening up of sequencing technology, so we can sequence genomes, and then also the ability to go in and edit genes. And so this would be, for example, CRISPR. And so now that we can sequence genomes and we can edit the genomes, we can go in and ask at a molecular level, what’s going on in the biology of these really cool animals?

IRA FLATOW: Well, we wish you great luck in doing this. And we’re very– well, it’s Cephalopod Week. It’s wrapping up. You’ve wrapped it up very well for us. We have certainly a lot of stuff to look forward to next year’s Cephalopod Week. Thank you very much, Dr. Alberin.

DR. CAROLINE ALBERIN: Thanks so much.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. She does a great job– Dr. Cari Albertin is cephalopod researcher at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. And now as we close the book on Cephalopod Week 2019, it’s time to bring back the ringleader of it all, the chair of our cephalopod party, the sage of suckers, Lauren Young, SciFri digital producer.

LAUREN YOUNG: Hey, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: It’s been a whole week, an exciting week.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, that title tickled my heart a little bit. That’s really great. Yeah, we’ve been getting down and squiddy with it for eight straight days. We’ve been watching lots of videos, m and reading articles, going to events, learning so much about these amazing invertebrates. It’s been a lot of fun.

IRA FLATOW: All right, so tell me, what was your favorite ceph discovery this week?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, I’ve actually been really amazed by how long cephalopods have been on Earth. So one of them that I’ve learned this week is about the ancient ammonite. So it’s unfortunately an extinct cephalopod related to today’s squid and octopus. But you actually might already know what it looks like.

It’s that super common spiral fossil that sort of looks like a snail shell. That’s a shell of an ammonite. And you can find those fossils all around the world. And during the age of the dinosaurs, these are the cephalopods that ruled the seas for about 300 million years, actually.

So they were abundant. And they had tons of shapes. Their shells had tons of shapes. Some were as large as car tires, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Car tires, wow.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, they were huge.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a big shell.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, that’s a pretty big shell that they had to carry. So what’s interesting is that those shells that they left behind– researchers can find out a lot about what ancient ecosystems in the ocean were like. So Kathleen Ritterbush and Nick Hebdon at the University of Utah, they take those shells. They 3D scan them.

And they run simulations of how the ammonite used to swim. So then they can zoom out on the larger picture using that data to figure out what oceans were like back in the day of the dinosaurs.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. How can these fossils tell us about the ocean today?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, so it’s really interesting. Kathleen said something to me. She said that we’re moving into cephalopods world–

IRA FLATOW: I like that.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, right? That would be a really cool world to live in. And so scientists– there was a study a couple years back where scientists noticed there was a boom in cephalopods populations. And it’s been growing since the 1950s in the ocean.

So it just so happens that Kathleen is studying a past ocean that’s filled with cephalopods, including the ammonites. So she can use that information that she’s collecting on the ammonites to piece that together. And you can learn more about her work and play around with some of the 3D scans that she does on our website at sciencefriday.com/cuddlefish.

IRA FLATOW: And this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios talking about wrapping up our Cephalopod Week. OK, so how do we know how the ammonites went extinct?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, so they were unfortunately wiped out alongside with the dinosaurs– so during that big mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. But something Kathleen mentioned that she really wants to know is why certain cephalopods had snuck through that mass extinction. So we know the chambered nautilus species of the chambered nautilus were around during that time. Somehow, they made it through. But the ammonites didn’t. So that’s one of the big research questions they want to look into.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. I know we’ve learned all sorts of great ceph facts at SciFri this week. But our listeners have been contributing, also, right?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, they’ve been playing along. So we asked everyone for their favorite cephalopod in the sea. And you all definitely delivered.

So earlier, you heard Chase gave a really great case for the vampire squid. I was also really amazed by David. His best cephalopod nomination was the morning cuttlefish.

DAVID: My favorite cephalopod has to be the morning cuttlefish or the two-faced cuttlefish. And the reason they’re so awesome is because, during mating season, while the big males are fighting with each other, the smaller males can’t compete with the large males. So they will disguise themselves as females, swim past the fighting males, and then sit next to the females so that when the females look at look at them they see that they’re male. But when the males look back, they’ll see that this disguised cuttlefish looks still like a female.

LAUREN YOUNG: So you could listen to more people geeking out over their favorite cephalopods at sciencefriday.com/cuttlefish. There is so many fun ones on there. So you’ve got to listen.

IRA FLATOW: And speaking of fun, we were having a lot of fun on social media, right?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yes, so much fun. A lot of you joined in in really creative ways this year. So someone on Twitter had been sharing a bunch of their origami cephalopods throughout the week. We also had kids send us their cephalopod drawings. You heard earlier someone reciting a poem, Octopus, Octopus, which was really great.

Our friend Sarah McAnulty, squid sage and biologist– who we love very much and has been on the show– she celebrated Cephalopod Week out in Hawaii, Ira. I’m so jealous. And she was out catching bobtail squid on a trip with Atlas Obscura. So they showed a bunch of videos and photos, which you can see some of these examples on our site, too, on sciencefriday.com/cuttlefish.

IRA FLATOW: Well, our listeners don’t want to stop. We actually have some calls coming in. Let’s go to Jim in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Hi, Jim.

JIM: Hey. When I was in fourth grade, we had to do a report. And I was into fossils and that kind of stuff. So my report was on the evolution of cephalopods, which totally freaked out my fourth grade teacher. But my favorite cephalopod is an ammonite.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yes. I’m converting everyone onto the team ammonite. It’s great. I know some other staff members might be a little upset.

IRA FLATOW: What made you– why was ammonite your favorite one?

LAUREN YOUNG: I was just amazed by the legacy, I think, that they left behind. They just, again, opened up this big window for paleontologists to look back in time and understand things like mass extinctions and ocean ecosystems of the past. So I find that fascinating.

IRA FLATOW: Jim, when you did your report, you found it very exciting– those, in particular, the ammonite.

BILL: Well, I also like the argonauts, the paper nautiluses.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yes, that’s my other favorite ones, too.

IRA FLATOW: All right, we’re in great agreement. So is the cephaloparty completely done? Are we done for the year, cleaning up the streamers, sweeping up the confetti?

LAUREN YOUNG: Right. We’re partying up to the very, very last minute for Cephalopod Week this year. So if you’re in the Philadelphia area, come on out of your shells, everybody. Because we have one Cephalopod Movie Night of the Week. That’s tonight. There are just a few tickets left. So make sure you get them at sciencefriday.com/cuttlefish. It’s all right there.

IRA FLATOW: You’re going to give us that URL again?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, sciencefriday.com/cuttlefish.

IRA FLATOW: You got any favorite cephalopods facts last minute?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, last minute– I could fill the very last second with cephalopod fun. So something else I learned, too– we did a Reddit AMA with a few cephalopod researchers. And Louise Allcock, who is actually an evolutionary cephalopod researcher– she mentioned that cephalopod ink can be preserved for 160 million years in fossils.

So researchers found a cephalopod fossil still with ink in it. And it turns out, that ink is still common to modern cuttlefish.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That’s a great way to end it. Thank you, Lauren.

LAUREN YOUNG: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Lauren Young, our SciFri digital producer and our ink-credible cephalopod party planner. And if you have a cephalo-fomo, you can check out everything from this year’s Ceph Week on our website at sciencefriday.com/cuttlefish.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.