Clearing Up The ‘Art Acne’ On Georgia O’Keeffe’s Paintings

8:58 minutes

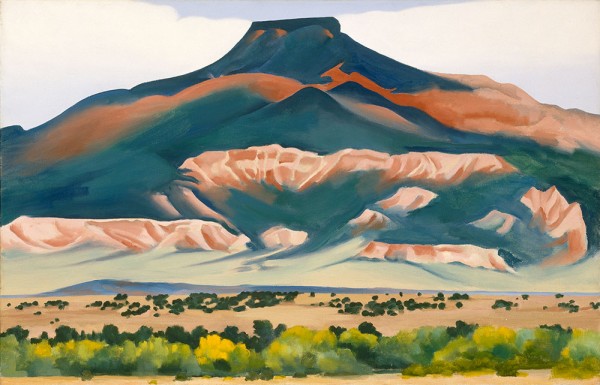

The painter Georgia O’Keeffe is known for her bold paintings of landscapes and flowers. When talking about those famous flowers, she said: “Nobody sees a flower–really–it is so small–we haven’t time–and to see takes time like to have a friend takes time.”

She took her small observations and filled her canvas with bright colors and close-ups, so those flowers couldn’t be missed. Recently, scientists took a closer look at those paintings and noticed smaller details that O’Keeffe did not intend to include. They found “art acne”—small pock marks—on many of her paintings caused by age and reactions of the pigments. Marc Walton, co-director of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts at Northwestern University and Art Institute of Chicago, talks about the chemistry behind the “art acne,” and how these paintings might be conserved in the future.

Check out some research images from the project below:

Marc Walton is a research professor in Materials Science and Engineering and Co-Director of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts at Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago. He’s based in Evanston, Illinois.

IRA FLATOW: The painter, Georgia O’Keeffe, is known for her bold paintings of landscapes and flowers. And when talking about those famous flowers, she said nobody sees a flower, really. It is so small, we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.

She took her small observations and filled the canvases with bright colors and close ups so those flowers could not be missed. But if you take a closer look at those paintings, there is a detail that you might miss which O’Keeffe did not intend. Scientists have found her paintings dotted with pockmarks due to age, art acne as it’s called.

My next guest is here to tell us how those small bubbles appeared and what it means for conserving these pieces. Mark Walton is the co-director for the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts at Northwestern University and Art Institute of Chicago. Welcome to Science Friday.

MARK WALTON: Hi, Ira. How are you doing?

IRA FLATOW: I’m doing fine. I’m quite fascinated by this. You’re calling it art acne. Is this something you can spot by just looking at the painting?

MARK WALTON: I love your quote from Georgia O’Keeffe, because it is the close looking of a painting that actually reveals these things. They are around 500 microns across, a little bit wider than a human hair, and if you look closely enough, you can actually see these protrusions forming. And Georgia O’Keeffe herself saw these and commented upon them when she was– during her lifetime, and it’s been an ongoing problem with these works of art ever since.

IRA FLATOW: So how were you called in about these dimples?

MARK WALTON: So I was called in because the conservator of the O’Keeffe Museum, Dale Kronkright, was doing a survey of his collection and he realized that paintings that she painted between 1920 and 1950 all had this distribution of protrusions across the surface. That’s what we’re calling this art acne, little bumps that are forming on its surface– on their surfaces. And he wanted to understand more about the material aspects of it, how they were forming, what are the underlying mechanisms, and then how can you monitor these things over the long run. For instance, he doesn’t just want to know what they’re going to look like in the next weeks or months, but he wants to be able to see how they’re going to deform, change, how their shape is going to appear in the next decades and hundreds of years.

IRA FLATOW: Well, speaking of hundreds of years, decades, or now, give us an idea of what is happening in the paint that is creating the acne.

MARK WALTON: So this acne is a phenomenon where you produce soaps within the paint film. These soaps are long chain organic complexes that have a carboxylic end-group, which is really a carbon and two oxygen. So it has a really strong negative charge and interacts with anything that has a positive charge. And those things that are in the paint film that interact with are pigments, and most abundant are things like lead white, which is a lead carbonate complex that will react with [INAUDIBLE], a metal carboxylate. These then will transport themselves through that paint film, aggregate, crystallize, exert pressure on the surface of the canvas and form these protrusions.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. And have you come up with a way to remove this acne?

MARK WALTON: Well, we’re not at that point yet. In fact, we are just trying to look at this, monitor them, trying to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms that are causing them to form. And then, maybe 10 years down the line, we’ll be able to come up with some sort of treatment. Pretty much, we want to be able to put the painting in the best possible environment so it doesn’t actually promote the growth of these sort of things, and that would be an environment where it would be appropriate type of relative humidity, light, temperature, oxygen to be able to prevent further growth of these protrusions.

IRA FLATOW: Does it get worse as the paint ages? Is there something happening there?

MARK WALTON: So you know, paintings are extremely delicate surfaces, and they are– when they’re exposed to the environment, they can undergo lots of different changes. It’s a dynamic process. So as that painting goes into a new environment, as it travels, it can actually promote the growth of these things.

And so what we’re trying to do is really try to correlate when they’re occurring, how they’re occurring, what sort of environments that they are going to be more prevalent in. And also, what are the underlying material causes, such as maybe there was an intrinsic vice with the materials that O’Keeffe herself was using when she was painting these works of art. We’re trying to chase this down to really understand what are the root causes of the problem.

IRA FLATOW: Now, George O’Keeffe didn’t go to the paint store or make her own paints, just her own type. There must be a lot of other paintings that have the same soap going on in the paint.

MARK WALTON: In fact, they are– there are many of them. This is something that is a problem on paintings across space and time. In fact, the first painting that this was discovered on was a Rembrandt. It was a colleague of mine at the Mauritshuis Museum in the Hague, in the Netherlands, working on a Rembrandt painting in which he first discovered these things, and that was around the mid ’90s when she first made the discovery that this was a problem in paintings. And since that time, around 40 scientists across the world have been working on it, trying to understand it and unpack what’s going on within the paint films themselves.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

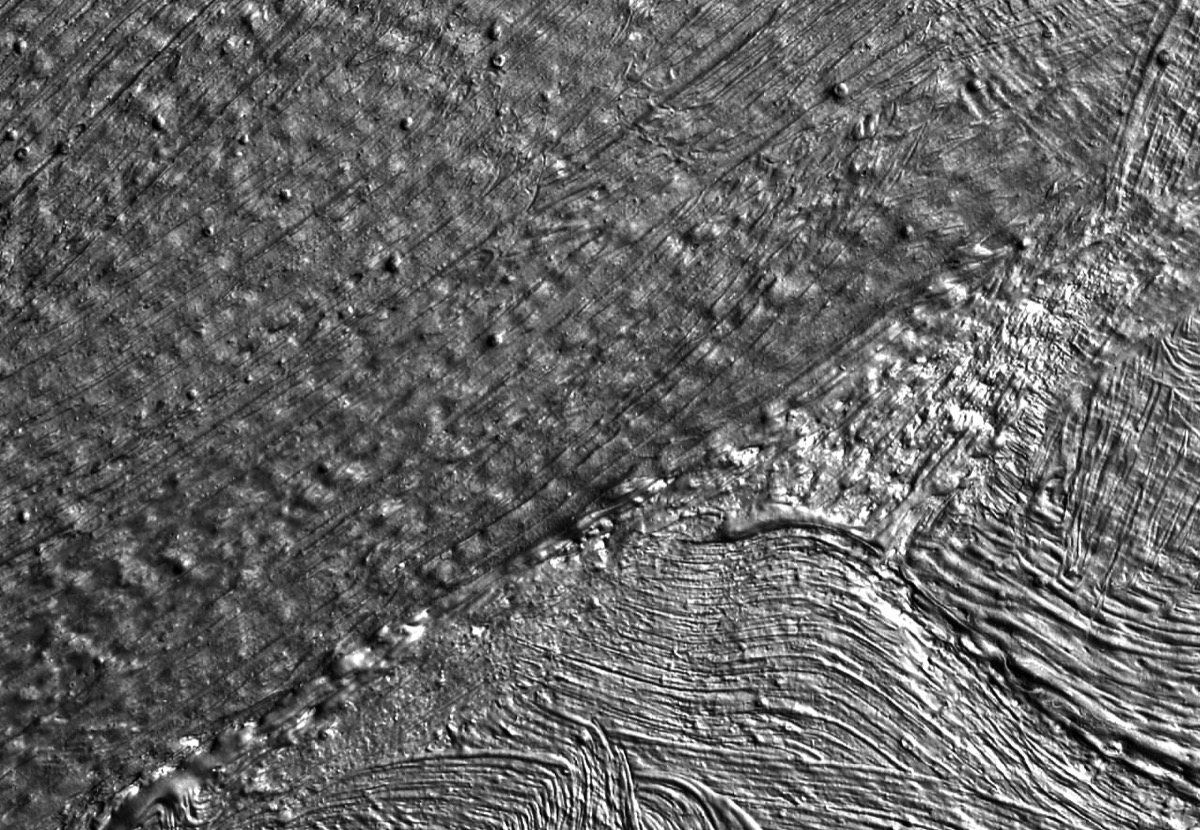

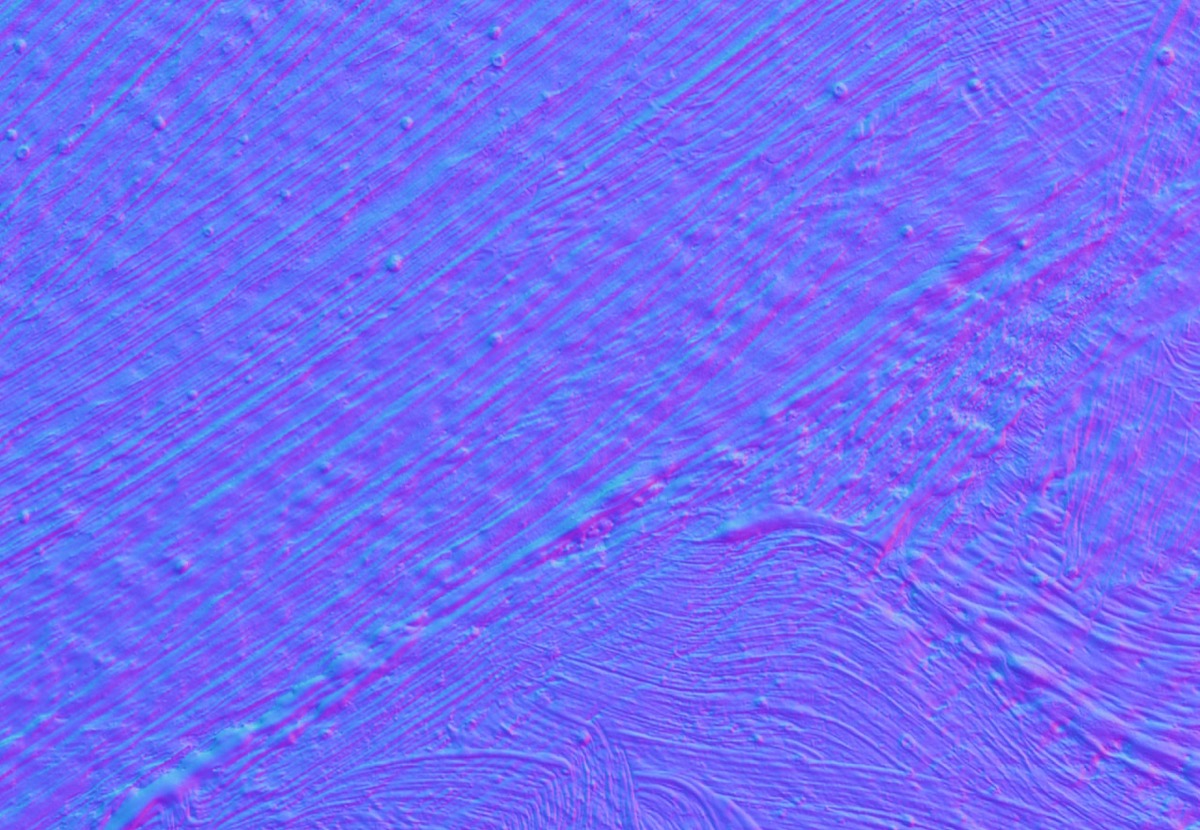

I’m also interested in the process. You made a map of the surface of these paintings. You took photos of the surface. Tell us how you discovered them and how you actually made a three– you could see the 3D of the images.

MARK WALTON: Yeah. This is actually at the core of our research. A lot of people have looked at the molecular mechanisms to be able to produce them. But what we didn’t really understand is how we can correlate all these environmental factors that I previously mentioned to the actual protrusions themselves. So we developed a three dimensional imaging technique to be able to strip away color from the painted surface and really look at the three dimensional structure. So I’ve been working with our Department of Computer Science here at Northwestern with signal processing experts to be able to really understand what that surface topography looks like.

When we first started down this path, we would have to use really very bulky, complex lighting stages, we would have to transport them down to New Mexico, and then we would have to manually do a lot of processing. And what we’ve been able to do is pare all that equipment down to a single device, an iPad or tablet, which has all the components already built in so we can create a three dimensional image of that surface extremely rapidly with just a consumer based device.

IRA FLATOW: OK. And can you make an app that everybody can use so they can discover it on their own paintings, painting restoration people?

MARK WALTON: This is what we’ve done, and we will be releasing this app for the iPad to be able to produce surface shape measurements of works of art. And hopefully we’ll be able to release this to the conservation, to the museum community with the next couple of months. The idea here is to be able to make both equipment, software that’s readily available that helps museums solve problems of restoration in a more effective way.

IRA FLATOW: Other kinds of stuff that use this kind– for example, does stained glass have this kind of problem also?

MARK WALTON: We are finding all kinds of different applications of our iPad device. One of the great strengths of it is that it really takes in the specular reflections off of a surface and is able to use those to be able to determine the 3D shape. So we’ve been using it on stained glass windows as well. We’ve been looking at Tiffany– works by Tiffany, by Lafarge, which are great stained glass makers from the turn of the century, and trying to understand where they got their glass, trying to trace it back to glass making factories by taking a look at the ripples or patterns in the glass that they used.

IRA FLATOW: And there’s really no way to prevent this then from the outset, unless you change your paints or–

MARK WALTON: Well, when we go– yeah, for the paints, it’s very difficult to be able to prevent it. It’s really caused by transport of water through that canvas. What is causing– it produces a hydrolysis reaction. This reaction then promotes further growth and interaction with the inorganic parts of the paint, and it’s part of the inherent vice of the type of materials that arts use anyway. It’s the job of the conservator to be able to make sure that the painting is in the proper conditions, to be able to understand the material composition, to be able to ensure its survivability into the future so it can be enjoyed by many people for years to come.

IRA FLATOW: So art conservatives recognize this now as a real problem.

MARK WALTON: It is one of the big challenges for painting conservatives right now is to really understand these material changes, to be able to understand how soaps interact with the overall structure of the paint, and understand the underlying agents of deterioration. Yeah, it’s a big problem for painting conservators.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you for bringing this to our attention, Mark.

MARK WALTON: It’s a great pleasure. Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Mark Walton is the co-director of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts at Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.