Citizen Scientists Will Capture DNA From 800 Lakes In One Day

8:27 minutes

Taking an accurate census of the organisms in an ecosystem is a challenging task—an observer’s eyes and ears can’t be everywhere. But a new project aims to harness the growing field of environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect species that might escape even the most intrepid ecologists. In the project, volunteers plan to take samples from some 800 lakes around the world on or around May 22, the International Day for Biological Diversity. Those samples will then be sent back to a lab in Zurich, Switzerland, where they’ll be analyzed for the tiny traces of DNA that organisms leave behind in the environment.

Dr. Kristy Deiner, organizer of the effort, hopes that just as lakes collect water from many streams across an area, they’ll also collect those eDNA traces—allowing researchers to paint a picture of the species living across a large area. She talks with SciFri’s John Dankosky about the project, and how this type of citizen science can aid the research community.

Sign up for Science Friday’s Beyond the Classroom newsletter to receive monthly fun, hands-on, all-ages activities for inspiring curiosity and experimentation—anytime, anywhere.

Dr. Kristy Deiner is an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Systems Science at ETH Zürich in Zurich, Switzerland.

SPEAKER: For the rest of this hour, something positive as we head toward Earth Day and a look at the way people around the world are cooperating to improve our understanding of global biodiversity. Taking an accurate census of all the life in an ecosystem is a pretty challenging task, and observers’ eyes and ears can’t be everywhere. But what if researchers could use nature itself to collect their samples? There’s a new project that aims to explore ecosystems via the environmental DNA, or eDNA, left behind in lakes.

Dr. Kristy Deiner is an assistant professor at the Department of Environmental Systems Science at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, and she’s coordinating this effort. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Deiner.

KRISTY DEINER: Thanks so much. I’m glad to be here.

SPEAKER: So tell us about this project. What exactly are you trying to do here?

KRISTY DEINER: We are trying to understand if lakes are acting like a biodiversity sensor in the landscape. DNA is coming off of every species where they live, and what’s special about water is that it’s flowing. And so once water comes from the landscape and ends up in a lake, what we’re testing is whether or not the DNA is sort of getting into this big lake and whether we can sample that, and it tells us all the species that are living in that landscape as well as what’s living in the lake.

If this works, what it does is it gives us a very effective way to sample biodiversity for the least amount of effort. Meaning that what we’ve calculated is there’s about 1.4 million lakes on the surface of Earth, and if we calculate that land around the lake that’s connected to the lake in its lake watershed, this is about 25% of the surface of Earth. And that would give us a really fast way to sample a huge amount of Earth’s biodiversity.

SPEAKER: Interesting. So why don’t we back up for a second, and when we talk about environmental DNA, what exactly do we mean? I mean, where is this DNA coming from?

KRISTY DEINER: Yeah, so that’s actually just being shed all the time from an organism. It can come from just interacting with the surface. We know this when we touch a surface ourself. We use this in criminal investigations, right?

They also are moving around in the environment and leaving maybe hair or pooping, and they can transport what they’re eating through that. So we also get signals of the movement of DNA because species are moving around, and they move around other species in their stomach with them.

SPEAKER: So you’ve got almost like a soup of these DNA samples in this lake. So how do you sort out who’s who in there and what you’ve actually got in this big-old lake soup?

KRISTY DEINER: Yeah, right? So over the last, let’s say, 50 or so years, scientists have been sequencing DNA from different species. And in that process, we’ve actually created databases where we know that that DNA came from a specific individual. And because we have that database, we know what unique sequences belong to certain species.

Now when we go to the lake soup, we find all these DNA sequences, but we have to sort them out. And so we do basically a matching game, like a puzzle. Does this DNA match with this DNA sequence that’s in our database? And if it does at the right amount of similarity, then we can assume that it’s from that species, and we can assign its taxonomic name.

SPEAKER: So how long does DNA stick around? I mean, you used the example earlier of people testing for DNA at crime scenes, and a lot of it has to do with how long that sample DNA might be able to exist in that environment. So is it possible that you’re actually going to be sampling DNA that was introduced into this lake environment years and years ago and the animal that left it behind doesn’t even live around here anymore?

KRISTY DEINER: That’s a great question. The answer is in water, we’ve done quite a lot of research to understand that DNA degrades relatively fast. This was a question we had at the beginning of the work, and what we know from all those scientific studies now is that the DNA degrades, most of it, within a few hours. But it can have a really long tail, and that can go out to almost a month. And because our measurement tools are so sensitive, we can actually detect that DNA that’s been around for even a month.

And when we did the modeling of how fast water actually runs off the landscape– I had no idea about this because I’m not a hydrologist, but I’ve worked with some now. And what we found is that water moves really fast. And for all those global lakes that we’ve looked at, that 1.4 million, we see that it only takes a few hours to a maximum of like five days to go from the farthest point in a river to get to that lake. So we predict that any lake should actually be working this way because the decay of DNA is not that fast.

SPEAKER: That’s really interesting. So I understand you’ve got a big day in this project coming up in May. Tell us what happens then.

KRISTY DEINER: Yeah, so when we thought about this project, we thought, what would be something that we could align this with that would be of interest to gauge whether or not we could get the attention of just ordinary people who’d want to participate in the project? And so we picked International Day of Biodiversity, which is May 22. Prior to that day, everyone who signed up for the project is receiving a little kit, and inside that kit, it’s about a 3-liter bucket. And inside that kit, there’s a little hand pump and a filter cartridge and a little hose and a little tube that they’re going to put the sample in after they filter water.

So they get this kit, and they bring it with them, and they go out to the lake. And the idea is that they sample close to where the rivers are coming in but still in the lake. And they go around the lake to hopefully 5 to 10 locations, and then at each location, they’re going to take that bucket, sample about that 3 liters or maybe a little bit less. And then they’re going to use this hand pump with the filter cartridge attached to it, and they’re going to filter the water through that.

And then they go to the next site and the next site and the next site, and at the end of the day, they will have hopefully sampled around 30 liters of water from that lake. And then they have to transfer this little filter into a tube, and that preserves it, and that can be stable at room temperature for like six months. And what we’re doing is having everyone send back their samples to ETH in Zurich, and we’re processing them there in our eDNA laboratory.

SPEAKER: How many of these buckets are you sending out? I mean, how many volunteers are taking part?

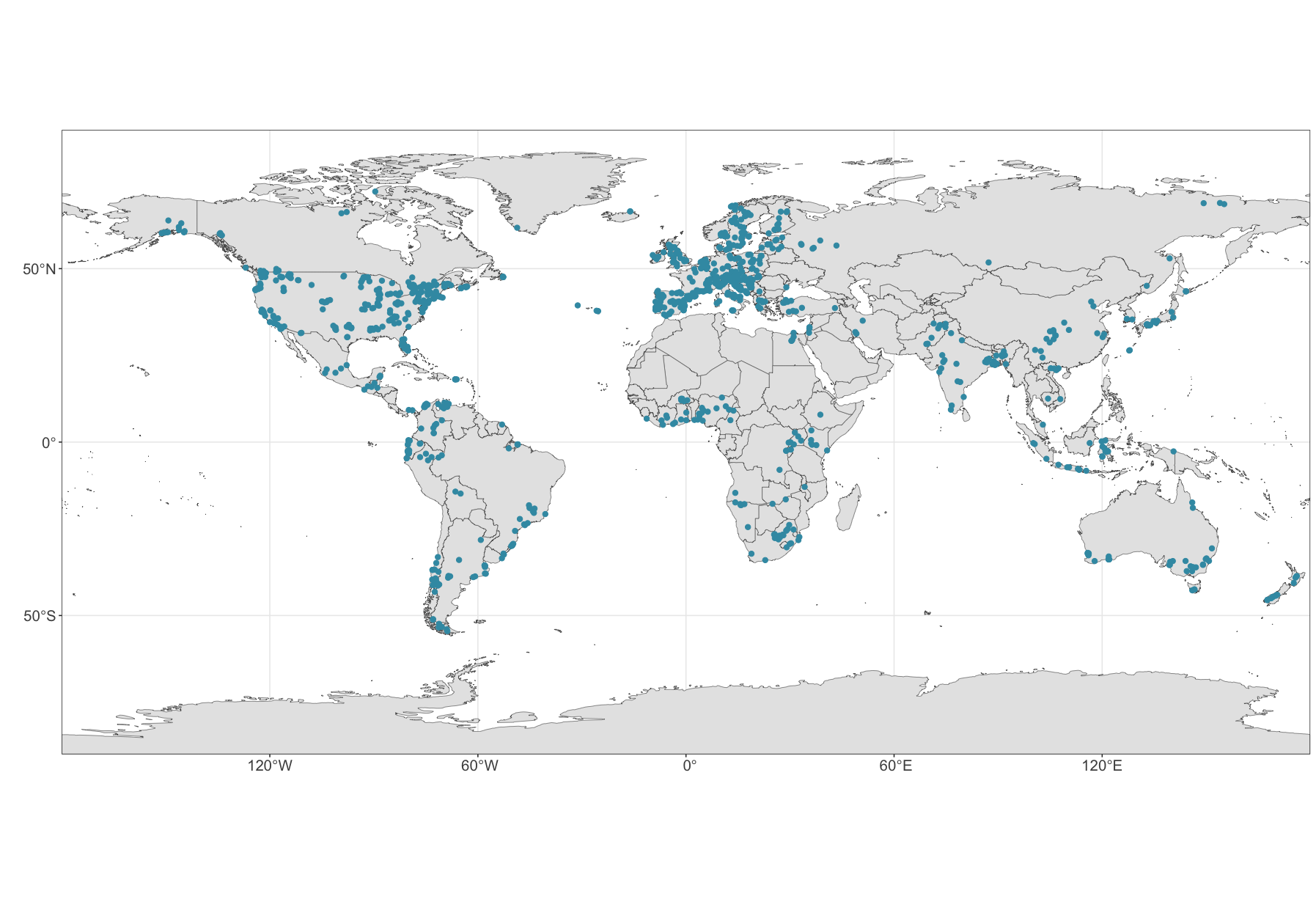

KRISTY DEINER: Yeah, so we have a goal of about 800 that will go out to a little over, I think, 500 different partners all over the world spread across 80 different countries.

SPEAKER: That’s fantastic. I’m sure that a lot of people who are listening right now are saying, I want to sign up. Can I still be a volunteer, or have you closed this out now?

KRISTY DEINER: Yeah, we have closed it out now, unfortunately. But if we’re really successful, the end game here is actually that we can turn this into a biodiversity monitoring system. So if we show this works really well, then it may be something that we can implement locally, and then we can maybe use this International Day of Biodiversity in the future as a means for us to all get out and generate the data that we need to understand what’s happening to our ecosystems.

SPEAKER: It really is an exciting project. I want to thank you for sharing it with us today. Dr. Kristy Deiner is an assistant professor at the Department of Environmental Systems Science at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. Thanks so much, Dr. Deiner. I appreciate it.

KRISTY DEINER: Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Sandy Roberts is Science Friday’s Education Program Manager, where she creates learning resources and experiences to advance STEM equity in all learning environments. Lately, she’s been playing with origami circuits and trying to perfect a gluten-free sourdough recipe.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.