ChatGPT And Beyond: What’s Behind The AI Boom?

31:59 minutes

Listen to this story and more on Science Friday’s podcast.

The past few months have seen a flurry of new, easy-to-use tools driven by artificial intelligence. It’s getting harder to tell what’s been created by a human: Programs like ChatGPT can construct believable written text, apps like Lensa can generate stylized avatars, while other developments can make pretty believable audio and video deep fakes.

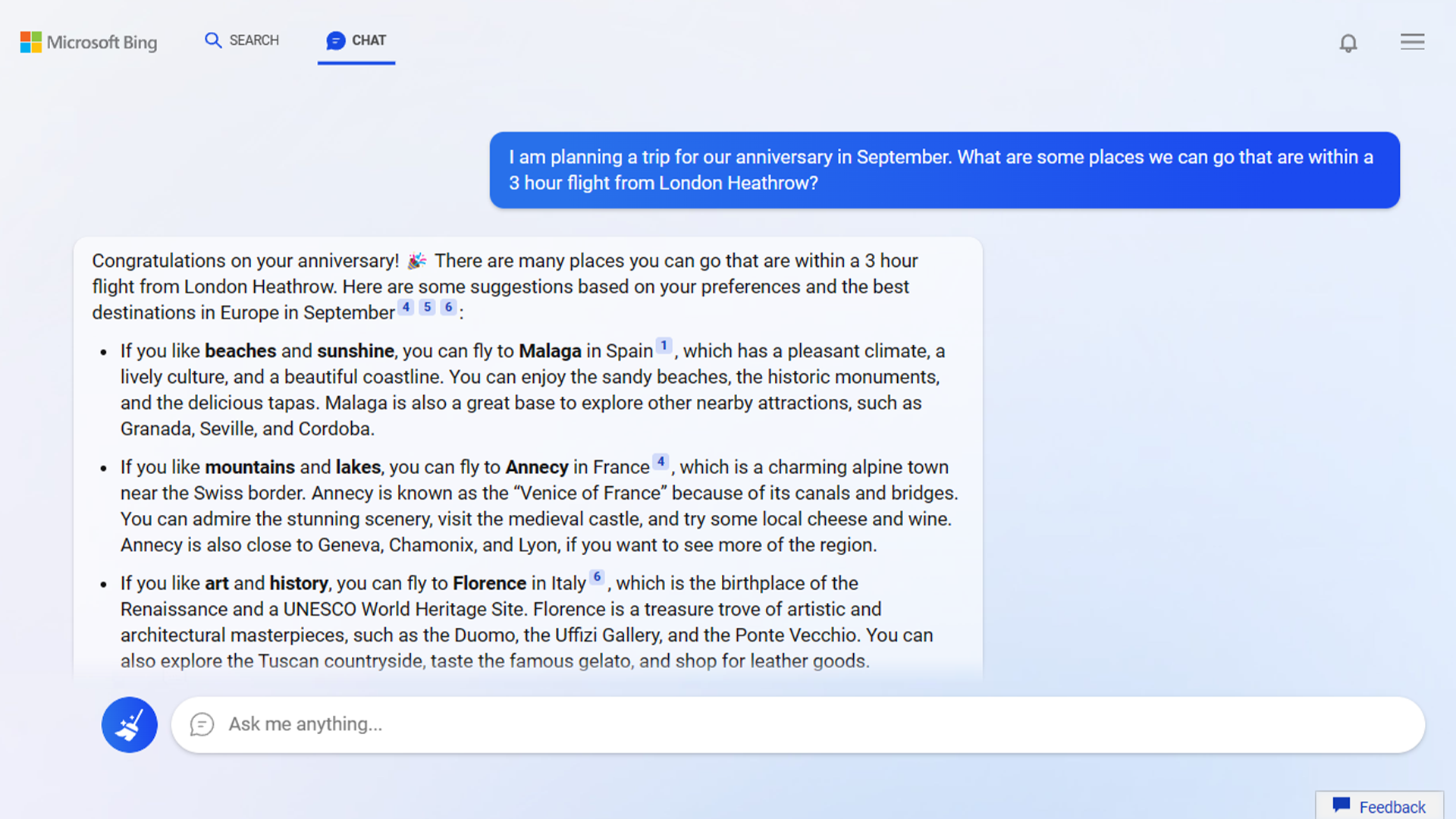

Just this week, Google unveiled a new AI-driven chatbot called Bard, and Microsoft announced plans to incorporate ChatGPT within their search engine Bing. What is this new generation of AI good at, and where does it fall short?

Ira talks about the state of generative AI and takes listener calls with Dr. Melanie Mitchell, professor at the Santa Fe Institute and author of the book, Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans. They are joined by Dr. Rumman Chowdhury, founder and CEO of Parity Consulting and responsible AI fellow at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The past few years, it’s been harder and harder to keep the squirrels from my prize tomato plants. It’s been, well, nuts. So this year, I’m giving up. I’ll set dishes of nuts right under the tomatoes and build a ladder to make it easier for the squirrels to reach them.

Wait a minute. That wasn’t me. I didn’t say that. That was actually an AI-generated version of me, and we did it by feeding audio samples of me into a program called Descript.

It’s the first time I’ve heard this, so this is just as surprising to me as it is to you, but it’s not quite perfect yet as you can hear, I hope. I think I still have a job. Well, we’ll see for now, at least.

Well, even so, it’s getting harder to tell what’s human and what’s not. There is a growing number of programs popping up where you can create deep fakes of audio and video to make people appear to say things that they actually have not said, like ChatGPT. Maybe you’ve tried that out if you have patience enough to wait on line to get in. Or others like Lensa, and then there’s Stable Diffusion that create images.

And just this week, we saw Google unveil their new AI-driven chatbot called Bard. Wonder if Shakespeare is spinning on this. And Microsoft announced that they will be using ChatGPT within their search engine, Bing.

Now, let me ask you. Have you used ChatGPT, maybe to write a paper or a work assignment? Are you worried about the ethical implications of this new technology?

That’s what we’re going to be talking about. What direction would you like to see AI apps go? You make the call, only if you make the call. Our number is 844-724-8255, 844-SIDETALK, or you could tweet us @SciFri.

Let me introduce my guest. Joining me to talk about the current state of what is called– what is called generative AI, Dr. Melanie Mitchell, professor at Santa Fe Institute, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, author of the book Artificial Intelligence– A Guide for Thinking Humans, and Rumman Chowdhury, founder and CEO of Parity Consulting and the Responsible AI Fellow at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard in Cambridge. Welcome, both of you, to Science Friday.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Thank you for having us.

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re Welcome. Dr. Mitchell, let’s start off. Let’s talk– start with what seems like a basic question that’s actually kind of difficult to answer. What is artificial intelligence? What does it mean for a machine or an algorithm, Dr. Mitchell, to have intelligence?

MELANIE MITCHELL: Yeah, that is a difficult question to answer because everybody has their own definition. So AI is really getting machines to do things that we believe requires intelligence in some form. So back in the early days of AI, playing chess was an example of something that people thought really required very high level general intelligence. And yet we were able to get computers to play chess without really using anything like human intelligence.

And now it’s gone even further. We’re able to get machines to produce language, and images, and other media in a way that looks very human-like. So whatever seems to require intelligence at the time, that’s what we call AI, is getting it in machines.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, so I would imagine, if you asked three different people, they would say three different things of what they think intelligence AI is.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Yeah, exactly. There’s many different definitions.

IRA FLATOW: Can you explain– briefly, I hope– how ChatGPT or similar chat programs work? It seems– almost seems like a bit of magic. You ask it to write a term paper, and it spits one out.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Yeah, so this is a– ChatGPT is a kind of what’s called language model, which is a program that’s learned from vast amounts of human-generated language. And the way it’s trained is it’s asked to– it’s given a text, like a sentence, and it’s asked to predict a missing word. And it’s doing that over and over again for huge amounts of data that it’s been trained on from websites to digital books, to all of Wikipedia, and so on.

And then now you can give it a prompt, like write an essay on the causes of the American Civil War, and it will then predict, in some sense, what words should go next over and over again, and will generate something that sounds very, very human-like.

IRA FLATOW: Listening to that little AI voice at the top of me, it doesn’t quite get the pacing or the intonation right. It’s amazing how it got my voice, I think, correctly. But there are lots of others that can do that, right? We just don’t have the Public Radio budget to pay for a better one.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Well, I think, also, we might need more data from your audio clips. So if it had enough data, it probably could imitate you pretty well.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Chowdhury, how have publicly available tools like ChatGPT, which generates convincing language– and then you have Lensa, convincing images and even programs that can create a fake voice. How have they changed our understanding of what AI is capable of?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: That’s a great question. So first of all, the big shift from, I would say, traditional artificial intelligence to generative AI is that the type of content that is being created by these models doesn’t exist anywhere on the internet, right? It’s not spitting back something that you see, like a search engine. It is actually creating this.

So when we think about these generative AI models, what I think about, as somebody who works in machine learning ethics and AI ethics, is what are the kinds of harms and stereotypes that exist in society that these machines can pick up on? So as Melanie said, these models are simply reflecting the data that’s being put into them. So all of these AI models are not any source of truth, but they’re actually reflecting what people have put into them.

IRA FLATOW: Melanie, are you surprised about how well this works?

MELANIE MITCHELL: Yeah, I’ve been very surprised. You know, I never thought that we could get human-like language generated with a machine that is so, in some sense, unintelligent. But it just goes to show how powerful huge amounts of data can be, and using a very, very large, complicated neural network program to make statistical models of that language, that is amazingly powerful.

IRA FLATOW: Now, one of the big concerns about these AI chat bots is how prone they are to making up facts– and other programs that create such realistic people– to convince you of the facts, facts which may not be really true. For example, this week when Google unveiled its new chatbot, Bard, it claimed that the Webb telescope was the first to take a picture of an exoplanet when, of course, we have lots of pictures of them. How big a concern is this, Dr. Chowdhury?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: It’s actually a fairly large concern. There have been issues of misinformation, fake news, and fake media for quite some years now. Really, the pivot that ChatGPT, and Bard, and a lot of the more readily available models do is now anybody can make it very easily. So we do have to be concerned about the type of media and how convincing it is.

I’ll also add that it doesn’t take a high level of sophistication to convince somebody of misinformation. You may remember the Nancy Pelosi video. Plenty of people still believe it’s true. It is not a high quality deepfake, so the change has not necessarily been in how good the quality is, but how easy it is to make it and get it out there.

IRA FLATOW: That is really interesting. Our number, 844-724-8255. Let’s go to the phones. Wynton in New Orleans, welcome to Science. Friday

WYNTON: How are you doing? Thank you for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: You’re Welcome. Go ahead.

WYNTON: Yeah, so I am an entertainment attorney. I work in intellectual property law, and I work with arts and entertainment professionals every day with copyright infringement and trademark infringement. And one of the biggest issues and worries I have surrounding AI-generated creative art is, A, the ethical implications, but also the potential impact it could have, A, on intellectual property law and, B, on the art and entertainment community as a whole, as the Copyright Office has already come out and ruled that AI-generated creative works are ineligible for copyright protection.

And then we’ve seen– especially with some of my clients, we’ve seen them trying to figure out how to bring copyright– copyright and trademark infringement suits because they’ve seen AI-generated creative works that are eerily close to their work or have spit out their trademarked image within an image that was created. And I’m following really closely the class action lawsuit that was recently filed last month against Midjourney, Stability AI, and DeviantArt for copyright infringement after the Midjourney CEO admitted in Forbes magazine that, yes, it was being trained on hundreds of millions of artists’ work. And they did not reach out to them for any kind of compensation, or give them credit, or any of the traditional things you would do.

IRA FLATOW: All right, let me get a comment from my guests. Yeah, that seems like something that has not been dealt with, Melanie and Rumman. What do you say? Who wants to tackle that one?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: Yeah, so that’s actually something I’m– yeah, I can tackle it. It’s something we’ve been thinking about quite a bit, and excellent and completely spot on question about there’s going to be a lot of evolution in IP law and understanding intellectual property. The things I worry about– one of them has been mentioned, which is, how do we understand the origin and appropriately give people credit for the work that they’ve done?

And maybe I’m less concerned about the big name artists out there and more concerned with the small guy, right? The people who are trying to sell their artwork on Etsy or places on the internet, and now it’s been scraped by this model that treats the entire world like its test bed, and their art is being reproduced for free. And as accurately mentioned, there’s a lawsuit by Getty Images because it actually spits back images that still have the Getty copyright on them.

So I’m curious to see how intellectual property law evolves, but also on a more existential way of thinking about things, what does this mean for the future of creativity? So what does it mean when a famous celebrity can– maybe licenses themselves to be used, and an AI can just continue to generate Taylor Swift songs every day until the end of time. How can a real human being compete with that?

How can we introduce new and novel creativity? Because actually what this AI is going to do is continue to make very Taylor Swifty Taylor Swift songs. It is not going to be new, or different, or fresh. It’s just going to be a rehash of what we know.

So I actually– yes, the lawsuits matter. Yes, the IP matters because people should be compensated for their work. I also am concerned about the future of creativity in general.

IRA FLATOW: Wynton, I hope you got some satisfaction from that answer.

WYNTON: Yeah, I think it was spot on because it really goes back to the root of intellectual property, and even goes back to the founding fathers and why they found it so essential to include it in Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 to protect innovation and scientific progress in the country.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, thanks for the call. A lot of people don’t realize that the copyright law, or the ideas of copyright, are right there in the Constitution. They realized how important it was. President Biden mentioned in his State of the Union speech about trying to reign in Silicon Valley, but this would seem to be more than just involving Silicon Valley, Dr. Chowdhury. It involves everybody who’s participating.

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: It does. Absolutely. And, actually, prior to my current role, I was the director of machine learning ethics at Twitter, so I am fully aware of what’s going on in Silicon Valley. I mean, the other thing that these technologies are introducing is a real shift in– and a seismic shift in the market that is Silicon Valley. It is really interesting to see these actors like Stable Diffusion and OpenAI, not the big giants, where this is not coming out of Google– Google came second or third, right?

So it’s interesting to see that it’s not these big behemoths that are coming out with the state-of-the-art models, and actually it is these smaller startups. We also have others in the playing field– Anthropic, DeepMind, and they may be closely related or affiliated with these companies, but, again, they’re not Google proper. It’s not Microsoft proper. It’s not Amazon. So I think we’re also seeing a seismic shift as it relates to the tech layoffs and the declining tech revenues.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, just to reflect on what you just said, all these big companies, though, started with small companies or individuals. So this is basically reinventing the wheel. Let’s go to the phones, and go to Tim in– Tim in, is it Elmhurst, Illinois? Hi, Tim.

TIM: Hi, thank you for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, go ahead.

TIM: I have a question that I’ve asked a lot of people in the computer field, and I have yet to get a satisfactory or comforting answer. I just have to wonder, what is to prevent AI– what, if anything, is to prevent AI from developing to the point of self-awareness and self-control, possibly leading to a dystopian scenario like The Matrix, or The Terminator, or something like that?

IRA FLATOW: The singularity, as it–

TIM: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, Melanie, what do you say to that?

MELANIE MITCHELL: Well, there’s a lot to say to that that we don’t really have a good definition of what self-awareness is. We have it, but we don’t know exactly what causes it. It certainly has to do with having a body and interacting with the world– is something that these AI systems don’t do yet. ChatGPT generates language, but it doesn’t have any body or any way to interact with the world, and make things happen in the world, and get feedback to its body.

So I don’t think there’s a very strong chance that AI is going to become self-aware in any sense, at least not until we understand what that means better. And the kinds of dystopian things that we see in science fiction movies– we’re just quite far away from that right now, but I think the technology has a lot more sort of near-term dangers, the kinds of things we were just talking about having to do with human creativity, and copyright infringement, and the misuse of these kinds of AIs by humans. So the dystopia will come from humans. It won’t come from the AIs themselves.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Rumman, do you agree with that?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: Oh, absolutely, and she’s spot on to point to the people. So at the end of the day, it’s people who make these technologies, but you are correct that generative AI and ChatGPT is one step on the road towards artificial general intelligence as these companies want to build it. So that is the goal of these companies.

But, again, human beings are investing in these technologies, building these technologies, and it wouldn’t create its own sentience. And, again, this Melanie pointed out, we’re not even– we don’t even know how to measure well what human intelligence is, so how would we even calibrate a bar?

IRA FLATOW: Somebody says– Kara on Twitter writes, I use ChatGPT to write custom bedtime stories for my four-year-old. That’s kind of cool. Roberto from Chicago is concerned we’re losing human connection if we depend too much on AI.

And let me ask sort of a similar question to you, Dr. Mitchell. I want to talk about something that AI is not very good at, and that’s common sense, right? And you found that out firsthand when you asked AI about yourself, and it said that you had died.

MELANIE MITCHELL: That’s right. Early on, I asked a version of ChatGPT to write a biography of me, and it wrote a very good biography of me, except for the very last line, which said that I had passed away in November, 2022, which was kind of alarming. And one of the things that I figured out happened– it was basing that on somebody of the same name who had actually died, and it didn’t have the common sense to figure out that we were not the same person.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, yeah. Is that because it just didn’t do enough homework?

MELANIE MITCHELL: Well, it did– I don’t know exactly why, but it hadn’t looked at our two– the information we both had on the web. And any human would look at it and say, oh, yeah, these are totally two different people, but it hadn’t done that.

IRA FLATOW: That’s very interesting. Let’s go to the phones to Denver. Hi. Welcome to Science Friday.

DENVER: Hi. I was wondering what the impacts of AI is going to be on religion and– in more– a little more specifically, on the development of theology. And then also, what are the ethical and moral implications of chat– of AI-generated sermons?

IRA FLATOW: That’s a very interesting question. Dr. Chowdhury, you want to tackle that?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: I will do my best. Interestingly– well, interestingly, though, the Vatican and Pope Francis have actually been quite involved in AI ethics. So there are actually Vatican principles on the use of AI ethically.

I don’t think I can speak to whether or not sermons being generated by ChatGPT– I imagine it can, and you could probably try to do it today. I do think the thing that’s interesting is– and kind of related to the previous question– how people want to deify or anthropomorphize artificial intelligence. So the question is really astute in that we try to make these things human, and they’re not. They’re programs. They’re computer programs that run online.

So I think the interesting part, as it relates to theology, is human beings need or desire to have some sort of a higher creature or being that is maybe omniscient and omnipotent. And what that does for us and our direction in life– and maybe, again, I’m getting a little philosophical, but it is a fascinating question. I did have Rabbi Mark in Marco Island on to talk about it. Are you still there?

MARK: Sure am.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us what’s on your mind.

MARK: Well, ironically, anecdotally I had occasion recently to ponder– so when ChatGPT came out fairly recently– what the ability of the artificial intelligence program is to synthesize the abstractions of how people of faith extrapolate core values and ethics out of their own scriptural faith, and to apply it to contemporary issues of important national and international concern. So I asked ChatGPT, what does the Torah have to say about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? And it very scrupulously reported the Torah, or five books of Moses, is regarded as sacred by the Jewish people. The war in Ukraine is an invasion by Russia of Ukraine.

And then much as the Torah was written in the Bronze Age, it has nothing to say about the war in Ukraine. I posted this on a professional chat group for other rabbis with the observation, the wry punch line, that’s why they call it artificial intelligence. And many of my fellow sermon writers said, I think our jobs are safe.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you for sharing that.

MARK: Most assuredly. Congratulations on your program, and every compliment to your guest.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Thank you. Melanie, Rumman, any comment on the rabbi’s remarks?

MELANIE MITCHELL: Yeah, I think it’s interesting that it kind of refused to make the connection between the Torah and this current-day war. And that may be a result of it being– the ChatGPT being programmed by OpenAI to be very careful in trying to make such connections because there’s kind of a tradeoff between it being sort of truthful and not insulting, or not profane, or not harmful to humans, and it being able to generate interesting, good text. And so there you see something that it’s being extremely careful about. And I think some of that is– already is part of the guardrails that the company has put on it.

IRA FLATOW: Michelle writes a long Twitter note, but I’m going to just summarize the last part where it says, the issue is less about the AI and more about human gullibility, and the incorrect bias towards perhaps granting greater default legitimacy to something generated by a computer. Turn the lens on us more than AI. Melanie, what do you think of that idea?

MELANIE MITCHELL: Well, certainly humans have been anthropomorphizing computers ever since they existed. And, interestingly, the very first chatbot– it might be ChatGPT’s great great great grandparent– was in the 1960s, a program called ELIZA, a very, very simple chatbot that pretended to be a psychotherapist. Much, much stupider, if you will, than ChatGPT, and yet people thought that it really understood them and had very human-like qualities. So this notion of us being gullible in some sense or being more prone to believe that something that’s talking to us understands us, that’s something that’s very inherent, I think, in human nature.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think we might have a spy versus spy– I’m talking about one of our tweets that came in about, could AI correct political misinformation in real time? Could AI monitor stuff and try to decipher what is real from what is false? Could that be something useful it could do?

MELANIE MITCHELL: I–

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: I can take that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, go ahead.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Go ahead.

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: Sure, and short answer is yes. I think I don’t want to spend too much time either waxing overly poetic about it or saying it’s all bad. I do think that these are the kinds of things that we need to think about how this technology can be used intelligently. I do think that a machine– a machine learning model or AI model is able to encapsulate a lot of information, can actually provide helpful directional guidance towards things, right?

So imagine it as like an automated Snopes. Snopes is still human beings. If you’re unfamiliar with Snopes, it’s a website where you can debunk common myths that you’ll see online or maybe you hear in urban legends. And those are human beings, and human beings can be fallible, as well. I think things like this could be useful for something like that.

And actually related, we are already seeing– in the AI and machine learning world, we’ll call it adversarial testing, right? So for every good guy, there’s a bad guy, and then there’s another good guy.

So ChatGPT comes out. Students start plagiarizing exams. Now the OpenAI folks actually have a model to tell you if text is coming from ChatGPT. So the short answer is absolutely, and these are the things it could be used for very widely.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Could I add a little bit to that?

IRA FLATOW: Sure, sure.

MELANIE MITCHELL: So, yeah, I think that’s absolutely right, but it turns out that social media sites have been trying to get AI systems to monitor posts for hate speech and misinformation for a long time. And it turns out to be very difficult because it’s such an open-ended problem, and it’s very subtle, and it really requires a much deeper sense of understanding than these systems have. So I think it’s a harder problem than people think to just apply these systems–

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: Correct.

MELANIE MITCHELL: –to figure out if somebody is posting toxic speech or political misinformation.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any regulation–

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: Right.

IRA FLATOW: –that could help that?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: There is actually some regulation on the books. So there’s the Platform Accountability Transparency Act that’s just been introduced. There is nothing on the books quite yet. So when we’re talking about toxicity or misinformation, a lot of that sometimes, as Melanie has correctly said, can be very subjective. These are the debates going on in Congress literally right now, right?

IRA FLATOW: Right.

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: People having different perceptions of who should or shouldn’t be allowed to say what online, how they should say it, et cetera. And Melanie is totally correct. Where I do think models have been successfully used is giving directional information. Otherwise, you can’t parse out every piece of information online with human beings to see if it’s incorrect or correct. But, yeah, it’s– so the short answer is there is nothing clear. This is the kind of legislation that’s being tackled right now all over the world, not just in the US, and TBD.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones to Stefan, I think, in Kansas City. Hi. Welcome to Science Friday.

STEFAN: Hi, yeah, my question was about the race to zero, which is something as a– in a freelance contract artist’s world is something that really stinks because you’ll have a client who just says, hey, I can outsource your art to– out of the country or out of your market, price you out, and it hurts my prices. And this should, in theory, cut those clients out so I won’t have to worry about those clients who want something for nothing anyway. So I’m a little hopeful in that way. I don’t know what you guys think about that.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re saying this is a positive thing. You’re not fearful of AI because it eliminates the people that are not going to pay anything anyhow.

STEFAN: Right, and it can’t create large bodies of work with consistent styles anyway, so it can’t create a 32-page children’s book with authentic art style on every page. Yet, anyhow. And then leadership, even at my day job as a graphic designer, they can use the tools to give me a better first base.

So I don’t have to actually have three or four different rounds of, how’s this? How’s this? How’s this? I can get straight to something more like what they want, and that could save me weeks.

IRA FLATOW: All right, that’s something positive. Thank you, Stefan. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios talking about AI, ChatGPT. There was a little bit of optimism there from a few of our callers. Let’s talk about some of the major flaws that generate AI tools. We’ve been talking about those.

How about, what is GPT– what is ChatGPT or any of these actually good at? What’s their positives? Melanie, let me start with you.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Well, they’re very good at generating articulate fluent grammatical language. And this is something that could be very valuable, you know? I mean, people who are, say, not native English speakers– of course, ChatGPT is all English right now, but there will be other languages, as well– or people who want to generate something fairly generic, like an email, or a text, or something, or a short document, that’s all– it’s going to be an incredibly useful tool for that kind of thing.

It also can generate short answers to questions. This is what Microsoft and Google are basing their new search engine strategies on, that we can then ask the search engine a question, and instead of giving us a whole bunch of links to look through, it actually generates a short, concise answer. The problem, of course, is you can’t always trust it to be correct or truthful, or to contain the right information. But it has the potential to be extremely useful and help people in their daily work.

IRA FLATOW: Let me see if I can get a few more questions in before we have to go. Mike in New York. Hi, welcome.

MIKE: Hi, I’m an artist in Brooklyn, and I– this is more of a comment, but I’ve been thinking about the fact that so much of this technology is just based on the overall human kind of dump that we’ve done over the last X amount of years onto the internet. Maybe there’s an opportunity for some sort of UBI, some sort of give back to the population that has basically built this database.

IRA FLATOW: You mean people like you?

MIKE: Yeah, people like me, and so many people. People like you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you for that. So how would you see this happening, Mike? What would you see going on?

MIKE: I mean, it would be a big structural change to make that happen, but it just seems like, if all of this technology is really being based on all of our collective input into the world, there’s got to be a way for it to come back. I’m not– I make drawings and paintings for a living, so I’m not an economist, but that’s my thought.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask. Thanks for that call. Rumman, Melanie, what do you think? Is there a way to give back here, Melanie?

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: So–

MELANIE MITCHELL: I–

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: So–

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

MELANIE MITCHELL: Go ahead, Rumman. Go ahead, Rumman.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead, Rumman. Go ahead.

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY: OK. All right, they’re like, we’ll throw the hard question of UBI– no, and, interestingly, what was just said is something I’ve heard as well. How can we ensure that people are compensated for what they’re contributing to it?

So there are new– there’s actually a new model that looks into some of the image generation AI and actually can point at the images that were possibly used to train it. So that could be one way. I think the difficulty here is identifying exactly which images led to the output or what text led to the output, because, again, it’s not a search engine. It’s not directly spitting back something it’s crawling from the internet. It’s actually generating this from a wide range of things.

So I think the first problem to tackle would be, how do you– how do you do attribution? And then the second is, how should someone be rewarded? I mean, another thing is we could just take money out of this altogether and say, this should be a publicly available product, then, because if it is built on the labor of the world, then it should be available to the world. I think the thing that people are having issue with is not the existence of it necessarily, but the commercialization of it.

IRA FLATOW: You’ve gotten back to the driver of society. It’s all about the money and people making a profit off of these. These were not written just because somebody– or they’re not being produced just because somebody feels good about them. They’re there to make money, right? So let’s end on that.

I want to thank my guests, Dr. Melanie Mitchell, professor at the Santa Fe Institute, of course, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, author of the book Artificial Intelligence– A Guide for Thinking Humans; Dr. Rumman Chowdhury, founder and CEO of Parity Consulting, and she’s a responsible AI fellow at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard in Cambridge. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.