Charles Darwin’s Lesser-Known Eccentric Exploits

29:26 minutes

Before he became famous for his theory of evolution, Charles Darwin spent years observing barnacle species from around the world, playing music to earthworms, and feeding bits of raw meat to insectivorous plants in an attempt to stimulate them. In his new book, Darwin’s Backyard, biologist James Costa talks about how these and other lesser-known experiments brought Darwin closer to his big theory of evolution.

[Recreate Darwin’s experiments in your backyard.]

Costa joins Ira to talk about what these experiments reveal about how Darwin interpreted the world. Plus, biologist Dean Pentcheff of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County discusses how Darwin’s work on barnacles influences what we know about them today. Plus, neuropsychologist Peter Snyder joins Ira to talk about how he dug into Darwin’s handwritten archives and discovered a psychology experiment that challenged the idea of how people express and recognize emotions in the faces of other people.

James Costa is the author of “Darwin’s Backyard: How Small Experiments Led to a Big Theory” (W. W. Norton & Company, 2017). He’s also the director of the Highlands Biological Station and a professor of biology at Western Carolina University. He’s based in Cullowhee, North Carolina.

Dean Pentcheff is Project Lead at the Diversity Initiative for the Southern California Ocean and a research scientist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles in Los Angeles, California.

Peter Snyder is Chief Research Officer for the Lifespan Hospital System and a professor of Neurology and Surgery at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

It’s safe to say that Charles Darwin is a household name. He’s arguably one of the first scientists that you learn about. And of course, his theory of evolution is the basis for our understanding all about all the organisms on this planet, how everything is connected. All big ideas here.

But what’s less known are his do-it-yourself home experiments. Did you know about those? Well, my next guest calls him the MacGyver of experimentation. From the Beagle to his home, called Down House, he performed studies on everything, from earthworms to snails. He even used a severed duck foot in an experiment. I think we’ll get into that in a little bit.

He dabbled outside of biology into the realm of psychology, but even though his experiments touched on different subjects, he used them to gather evidence to support his theory of evolution. So what do these experiments reveal about Darwin as a scientist? We’re going to take a Darwinian deep dive with my next guest, James Costa, Professor of Biology in Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina. He’s also author of the new book Darwin’s Backyard: How Small Experiments Led to a Big Bang Theory. A big theory, not a big bang theory.

And his book includes step-by-step instructions for you to recreate. You want to recreate these experiments? You can read an excerpt of that book on our website at sciencefriday.com/darwin. Darwin’s Backyard How Small Experiments Led to a Big Theory. James Costa, welcome to Science Friday.

JAMES COSTA: Great to be here, Ira. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And if you have a question for his experiments and about Charles Darwin, our number is 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK. Sorry to butcher the title of your book, James.

JAMES COSTA: No worries.

IRA FLATOW: Welcome to the club. In your book, you write that Darwin’s experiments instruct as well as entertain, novel, amusing, at times hilarious, yes, but they also shine a spotlight on science as a process. Darwin was a prototypical MacGyver figure. Tell us about that. Why do you say that?

JAMES COSTA: Yeah. Yeah, you know, his experiments are– to me, they represent just pure, unadorned scientific inquiry. You know, just someone who is curious about what’s around him, is observing things closely, coming up with on the fly experiments, some of them maybe slightly on the wacky side, but trying to figure out what’s happening in the natural world.

And the very simplicity of those experiments makes them, I think, just eminently accessible for us today. They can be used to actually illustrate science at its most essential, really, in anyone’s home, back yard, school yard, et cetera.

IRA FLATOW: He does have critics. Some of his critics called him a superficial dabbler. Give us an idea of what Darwin’s experimentation style was like.

JAMES COSTA: Well, this was a time when, of course, experimentation in the life sciences, especially, wasn’t formalized, and so his curiosity was expansive. As you mentioned, he’s interested in orchids and snails and little plots of plants and earthworms and so on. And so at any one time, he might have a dozen different little projects going on, all literally in his backyard in the nearby meadows, woodlands. And they seemed very small in scale, and they would be addressing odd questions.

And so it was maybe easy for some to sort of laugh at them. And he, in fact, he had a self-deprecating sense of humor. He sort of poked fun at himself. He called them his fool’s experiments. But he was convinced that there was an interesting and serious point to be learned by them.

IRA FLATOW: You know, that’s interesting that you bring that up, because one of the things I learned about Darwin is that he sort of would be like a fun guy to hang out with.

JAMES COSTA: Absolutely, yeah. He’s well-known– the literature, reminiscences and such about Darwin, are clear. He had a real sense of humor from early on. He was a jokester. He would play little practical jokes on his friends and family, involve them in his various experiments. I think, by all accounts, he was a fun guy.

IRA FLATOW: He used his own toenails in an experiment?

JAMES COSTA: In at least one, yeah. He came upon some sundews, these little diminutive carnivorous plants, while he was searching for orchids one day. And he was a bit bored and thought, well, let me take a look at these, and was interested in their ability to eat– they are carnivorous plants. But he had never really looked closely at them.

And so he came up with just an on the fly little experiment to see, initially, what might they be interested in sort of, quote, unquote, feeding upon? And he fed them some of his hair and some of his toenails. And that was the sort of maybe inauspicious beginning to what became really interesting series of studies that culminated in a book. But in that initial experiment, they sort of metaphorically spit out the toenails. The sundews were not interested.

IRA FLATOW: When Darwin was on his famous trip on the Beagle, in his journal he uses the word observe over and over. But he only mentions the word experiment four times. Was he conducting experiments while on the Beagle?

JAMES COSTA: He was, without, maybe, consciously kind of thinking of them as experiments. In my book, I talk about how you see elements of Darwin’s penchant for these on the fly, quick and dirty curious experiments, even while he was on the Beagle voyage, like the one where he was throwing iguanas away from the shore to try to demonstrate that they really do swim back to the same spot. It was sort of conjectural whether they were truly marine lizard relatives. And there’s no other species like it, this marine iguana. And so he tried to test whether they would actually return repeatedly to the shore and were able to swim.

IRA FLATOW: And I know there are a lot of– I’m not going to call them wacky things– but they’re sort of wacky things, interesting stories and experiments in the book. And I know that you write about he collaborated with his fellow family members. And one of the intensive studies he talks about– or you talk about– he conducted with his family was on earthworms. They played music for earthworms? What were they trying to figure out? Whether they like Mozart or the Beatles? I mean, what–

JAMES COSTA: Well, probably some Chopin. You know, his wife Emma was an accomplished pianist, and actually she studied under Frederic Chopin at one time. So she might have been playing some Chopin. And his son Francis played bassoon. His little grandson Bernard played penny whistle.

The interest there– and this came pretty late, this was in the late 1870s– he’s interested in their sensibilities, their sense perceptions. And can they detect these sounds? And he maybe had a hunch that it was the vibrations that they were paying attention to. But he realized the absurdity of it, that here they are, all playing musical instruments to these earthworms. He had them in flower pots that he called wormeries. And he would put pots of his wormeries up on the piano and Emma would play, his wife Emma.

Then he would remove it several feet away from the piano and she would play. And then he would observe their reactions to the music.

IRA FLATOW: I know one of your favorite experiments of his involved a dead duck foot, trying to figure out the dispersal of snails. Describe that for us.

JAMES COSTA: Yeah. The duck foot experiment. He probably used more than one severed duck foot. And I’m sort of expecting they probably ate the ducks, and he just saved the legs. He was interested in dispersal in a very global sense, you know, how do species become distributed as we see them? And he thought that the powers of movement of species on their own, or by being carried by other organisms, that underlies a whole lot of dispersal.

And so when it comes to fresh water ponds, lakes, and such, when you have aquatic organisms like snails that can’t live very long outside the water, he’s wondering, well, how do they get from pond to pond and lake to lake? And so he devises an experiment, figuring that waterfowl must be responsible.

So he uses these severed legs, and he dangles them in what he calls a snailerie, which has an aquarium full of snails, and he wants to see if the snails will climb on board, and he’s watching them closely. And when they do climb on board on the duck’s foot, he pulls it out and he puts it on his mantel. He wants to see, well, how long can these snails survive outside of water?

And so he documents this repeatedly, and he’s trying to determine, well, if these snails can live, hanging on for dear life on these duck’s feet for hours, let’s say 20 hours, 24 hours, well, how far could a duck fly in that time? Well, conceivably they could be carrying these little snails hundreds and hundreds of miles.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. We don’t have a whole lot to get into this next question. But you talk about Darwin having a big blunder and the Glen Roy study about how shorelines were formed. And my question about that is, do you think this experiment influenced him later on to hold back on publishing his evolution theory? You mention that in your book.

JAMES COSTA: Yeah, I’ve wondered about that. Darwin was really gung ho and thought of himself as an up and coming young geologist when he returned from his voyage around the world on HMS Beagle. Geology certainly was a really hot, fascinating, exciting science at the time, and he saw himself as a geologist. And he was very gung ho and immediately threw himself into some of the interesting outstanding geological questions of the day.

And one of them had to do with these curious parallel lines that one could see on the landscape of Glen Roy in Scotland kind of etched in the hillsides. And he threw himself in with abandon. And he very quickly published, and all too soon came to grief, came to realize that he had really missed the boat. The science of glaciology was only just being born at that time in France or Switzerland. Charpentier, Louis Agassiz here in the US were developing the glacial theory.

And Darwin’s idea was that these lines were essentially fossil marine beaches. And he wasn’t too far off. They are beaches, but actually freshwater.

IRA FLATOW: From glaciers. And Yeah.

JAMES COSTA: Exactly. From glaciers damming this valley. So he really regarded that as maybe his greatest blunder, and he probably realized he was way too rash in jumping in. And I suspect that did play a role in his later caution. You know, he was determined to painstakingly collect evidence, especially in areas that he knew would prove to be rather controversial with his colleagues.

IRA FLATOW: Talking with James Costa, author of Darwin’s Backyard: How Small Experiments Led to a Big Theory. We’re going to take a break, talk more about Darwin’s do-it-yourself experiments. If you want to do it yourself, you ca n go to our website at sciencefriday.com/darwin, where you can read an excerpt of the book. And we have instructions there how to recreate this experiment. sciencefriday.com/darwin.

We’ll be right back after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour, in case you’re just joining us, about Charles Darwin’s a lesser known experiments. My guest is James Costa, Professor of Biology in Western Carolina University. He’s also author of a new book, Darwin’s Backyard: How Small Experiments Led to a Big Theory.

I want to bring on another guest to talk about another creature that Darwin meticulously studied for years. I’m not talking about the famous finches. I’m talking about the barnacle. Dean Pentcheff is a research scientist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. Welcome to Science Friday.

DEAN PENTCHEFF: Well, thank you very much, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You know, we know that Darwin was interested in barnacles. But why are you interested in barnacles? Give us your elevator speech about why we should care about barnacles.

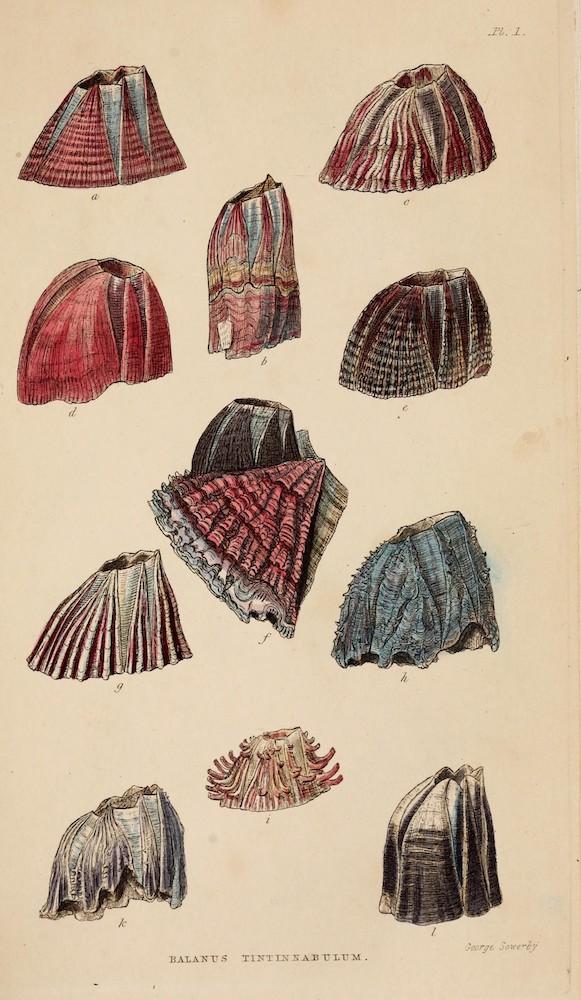

DEAN PENTCHEFF: Where do I begin? Barnacles are spectacularly weird animals, actually. So most people think of barnacles as the little white dots that plague their boats. But barnacles are organisms most closely related to crabs and shrimps and lobsters. And they look like a mollusk. They look like a little seashell with that white outer shell. But actually, inside there is effectively a little shrimp glued to the rock by its head, and using its feet to gather food from the seawater.

So these are organisms that, certainly at the time of Darwin, were reasonably well understood to be crustacea. They were known to be related to the crabs and shrimps and lobsters. But boy, are they strange, are they bizarre in the way they metamorphose and turn from a swimming larva into this shelled creature on the shore.

IRA FLATOW: So did he discover what they truly were?

DEAN PENTCHEFF: Not really. He was lucky enough to come into the field when there had already been a bit of work, really good work, done on barnacles. And for decades, centuries, there had been debate about are they mollusks? Are they something else? Because you know, they’re quite peculiar.

Shortly before he really dug into the barnacles, John Thompson, another researcher, had made the key connection by looking at the larvae of the barnacles and realizing, oh, these things that are floating around that look like crustacean larvae, these are barnacle larvae. Oh, OK. They’re crustacea.

So he had that in place already. But he just really dove in and really systematically studied all the barnacles he could get a hold of from collaborators, researchers, to really try to understand how they were all put together and what made them what they are.

IRA FLATOW: Did they help him shape his theory of evolution at all?

DEAN PENTCHEFF: I think there’s good evidence that they did. The barnacle work that he did was the big project that he was working on just at the time that, essentially, his bluff got called and the letter from Wallace arrived, and it became clear, and he was leaned on by his friends to publish his theory of natural selection.

The focus of his work at that time really was barnacles. In the work, you can sort of see him struggling with the same kinds of fundamental ideas that he was trying to work out in Origin of Species. What are the origins of these different structures? Why is it that particles are similar to each other, different from each other? Those are the kinds of questions that are answered in Origin of Species. But the substrate that was causing him to really chew on those questions at that time was barnacles.

IRA FLATOW: Jim Costa, you agree?

JAMES COSTA: Yes, I would. I think it’s fair to say he sees in barnacles bizarre adaptations. They have very strange sex lives and a superabundance of variation in all of their parts. I think he sees them as sort of evolution in action. He’s especially interested at that phase, I think, in the evolution of separate sexes.

His idea is that evolutionarily, all groups of organisms start having both sexes kind of contained within the same individuals, but that over time they become separated into individual males and females. And he thinks he sees this dynamic process unfolding in the world of barnacles because of their very bizarre sex lives, often with these very minute males that sort of adhere to the outside of the females. Very strange.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Let me ask this of both of you. Do you think that Darwin could have existed today in the way we do science now?

DEAN PENTCHEFF: Oh, he was an extraordinarily thorough scientist. And by the time of Origin of Species, he was already, as James has said, he was already a very well-respected scientist for all the work that he had done to then.

Science at that time, it worked at a different pace. There weren’t the kinds of journal publications that we are used to today. There wasn’t email. People wrote voluminous letters to each other. That’s how things got exchanged, that’s how ideas got exchanged. So he worked at a slower but much more thorough pace than I think we’re used to today. The kind of work he did, these four volumes on barnacles, would be pretty unusual for a single researcher to do today. Does it happen? Yes, absolutely. But we’ve shifted to a much higher feedback rate mode of doing science.

IRA FLATOW: Jim, you agree?

JAMES COSTA: I would agree. You know, Dean makes a really good point. Some historians would regard Darwin as the last of the great so-called country house scientists. So these were scientists that really were fairly well-off. They had the luxury of time and resources to really– those that were interested in the sciences– to truly delve very deeply into the subject.

And that’s an interesting way to think about Darwin. You know, he’s also literally conducting his experiments and such at home. This is in the late 19th century, the cusp of a transition to the professionalization of science, where it really is beginning to be done more under controlled conditions in well-designed laboratories, and we’re formalizing statistical analyzes and experimental design. So I think I would agree with Dean. He really had the luxury of delving very, very, very deeply without the kinds of pressures that scientists experience today.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Dean, I want to thank you for taking time to be with us today.

DEAN PENTCHEFF: Well, thank you for letting the Natural History Museum have a part in this. We really appreciate it.

IRA FLATOW: We were happy to have you. Dean Pentcheff is a research scientist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles.

You’re probably getting a sense that Charles Darwin’s interest reach beyond biology. He was interested in sea creatures and birds and finches. But he was also trying to understand people. My next guest was able to go into Darwin’s original archives, and he found a little known psychology experiment conducted by Darwin.

Peter Snyder is a Professor of Neurology and Surgery at Brown University. Welcome to Science Friday.

PETER SNYDER: Thank you, Ira. Thanks for having me. And hi, Jim.

JAMES COSTA: Hey, Peter.

IRA FLATOW: Peter, you actually found Darwin’s notes where he was disagreeing with a theory put out by the famous neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne? What was Darwin’s take on that theory?

PETER SNYDER: I did. I was spending about a month and a half at Cambridge University’s Library. I had the luxury and pleasure and honor to be able to really dive into the collection. And I was very interested in his work in the late 1960s– I’m sorry, 1860s and early 1870s– when he turned his attention, after publishing Descent of Man, to look at the human condition, and to better understand how we fit in to the grander evolutionary theory that he became so famous for.

And he was interested, at the time, in the expression of emotion. He believed that the emotion expression in humans is not substantially different across races and cultures, across the planet, and that it fits into the evolutionary line with other primates, that this function is conserved.

And at that time, Duchenne, the French neurologist, believed that humans were unique in the animal world, and that we had myriads of different facial muscle groups, each muscle group specific to conveying a different emotion. And Darwin just didn’t believe it. He had a copy of Duchenne’s folio because of photographs where Duchenne stimulated muscle groups in an actor that he paid to make the muscles contract piece by piece in the face, and to create emotions, some of which, in some of these images, look normal and appropriate as human emotions, and some, frankly, just don’t look real to the naked eye.

And Darwin had this portfolio, and he simply didn’t believe that there were 60 different emotions that were unique to humans. He really believed that there were a smaller set of just a few cardinal emotions. And he set about to try to figure out what those were.

IRA FLATOW: Did he find out what they were?

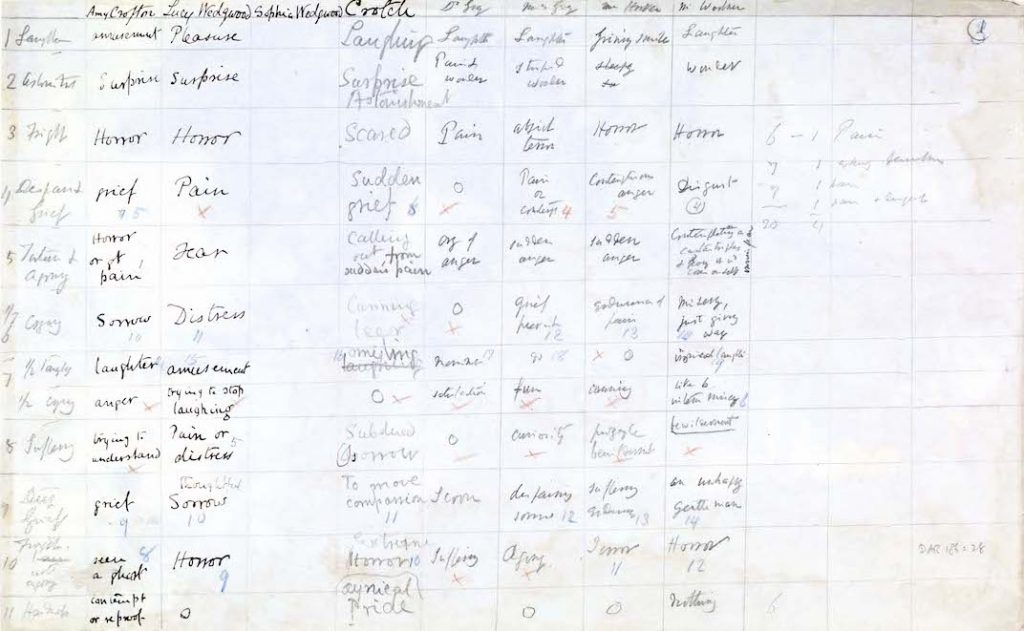

PETER SNYDER: Well, he did a really unique thing for his time. He actually did run a single blind psychological experiment in his home with 24 family members and guests that came to Down House, one after the other.

And what he did was he took a subset of Duchenne’s images, and he showed them to each person one by one. And he made sure that he was not asking leading questions. He simply asked, please look at this image and tell me what emotion you see.

And either he or his wife, Emma, wrote down on a table that covers three pages what the responses were for each respondent. And you had the respondent’s name on the y-axis and the date that they visited. And then you had a column for each of the images that were shown, and then what the responses were. And then in pencil mark off to the side, you see Darwin tabulated the results.

And the ones where there were the greatest agreement across the respondents, these 24 visitors or family members, the images where there was the most agreement, those were the ones that were turned into woodcut prints that went into one of his great books, The Expression of Emotion in Animals and Man.

IRA FLATOW: And Jim, Darwin was also testing his ideas in babies, was he not?

JAMES COSTA: He was. And this fabulous experiment that Peter so nicely described kind of was an extension, I think, of this broader interest, not only in understanding sort of universal aspects of the human experience, but also ultimately relating humans to other animals.

So that book that Peter mentioned, the expression of the emotions, the full title refers to in man and animals. And he’s ultimately looking at, really, the similar sorts of what you might call facial expressions, emotional expressions in other animals. And that involved looking at infants as well, looking at babies, trying to get a sense of infant expressions as the most essential, basic expression of certain emotions. He had a notebook.

IRA FLATOW: It looks like he was very intuitive thinking, that he would act on an intuitive idea.

PETER SNYDER: He certainly was. In addition to babies, he was also studying emotion at the same time in psychiatric patients. He had a long correspondence with a very famous psychiatrist and the rector of one of the largest lunatic asylums in Britain at the time, James Chrichton-Browne.

And he believed, Darwin believed, that by studying emotional expression in psychiatric patients, you had this opportunity to have an unbridled, unfiltered look into raw human emotion in individuals who were, for psychiatric reasons, not covering or acting or paying attention to social graces. It was just the raw human emotion.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking about Darwin. Could he be accused of today– if he were a researcher today– of overstepping his boundary of expertise by going into human research, as opposed to the animals and things he studied on islands?

JAMES COSTA: Well, Peter, would you like to–

PETER SNYDER: Sure, yeah. You know, I think, actually, he should be celebrated for this. You know, we’ve spent so many decades of time as individual researchers in our own domains, in our own silos, working on our own projects. And the new trend in science across the biological sciences can be characterized by multi-disciplinary team research. And some of the most important insights in biology are coming from crossing disciplines.

And Darwin, so long ago, had the tenacity to do this. And he wasn’t afraid to push new ground. He wasn’t afraid to really push himself. And he was a remarkable individual for that reason.

IRA FLATOW: Well, why do you think we don’t remember him for most of these things? I mean, has evolution so crowded out all these other achievements?

JAMES COSTA: Well, we remember him for the outcome, for the incendiary book On the Origin of Species. But those that take the time to read that book, they see the painstaking efforts that have gone into building an evidentiary case, subject after subject, a book that he called one long argument and yet has many different subjects, hybridism, domestication, geographical distribution, fossils.

So we remember the sum total, which is really the total, the book in its entirety, in some very important, I think, philosophical and scientific ways, is greater than the sum of its parts. So I think that it’s seldom read, maybe too seldom read in detail, or people would be, I think, more aware of the way he went about making a case for his arguments.

IRA FLATOW: Peter, you agree?

PETER SNYDER: Oh, I do agree. I also think that there is an issue with the sheer volume of the work that he produced. He wrote 22 books. He published many, many monographs. His letters to his peers and to colleagues and to people he admired covers 80,000 pages of documents. The collections that he amassed of specimens, both when he was on the Beagle and afterwards, are just immense. So it’s very hard to really wrap one’s head around the totality of what he accomplished in his career.

And probably, just really honing in on Origin of Species, and perhaps maybe Descent of Man as a second important work of his, is an easier way to really wrap your head around what Darwin accomplished.

JAMES COSTA: True. And might point out, too, that specialists would be, perhaps, more interested in some of the more narrowly focused books that came after these, books on carnivorous plants, for example, climbing plants, earthworms and such.

IRA FLATOW: You can see how that naturally comes out of reading your book, Jim, and it’s a great book. The book, James Costa’s book, is called Darwin’s Backyard: How Small Experiments Led to a Big Theory. Quite a delightful read. I learned so much about Darwin from that. I want to thank you for writing it and being a guest with us today.

JAMES COSTA: Oh, great pleasure. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And Peter Snyder, Professor of Neurology and Surgery at Brown University. Thank you, too, for sharing what you know about Charles Darwin.

PETER SNYDER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Sushmita Pathak was Science Friday’s fall 2017 radio intern. She recently graduated from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism and majored in electronics and communication engineering in college. She sometimes misses poring over circuit diagrams.