CAR-T Cell Therapies Show Promise For Autoimmune Diseases

11:56 minutes

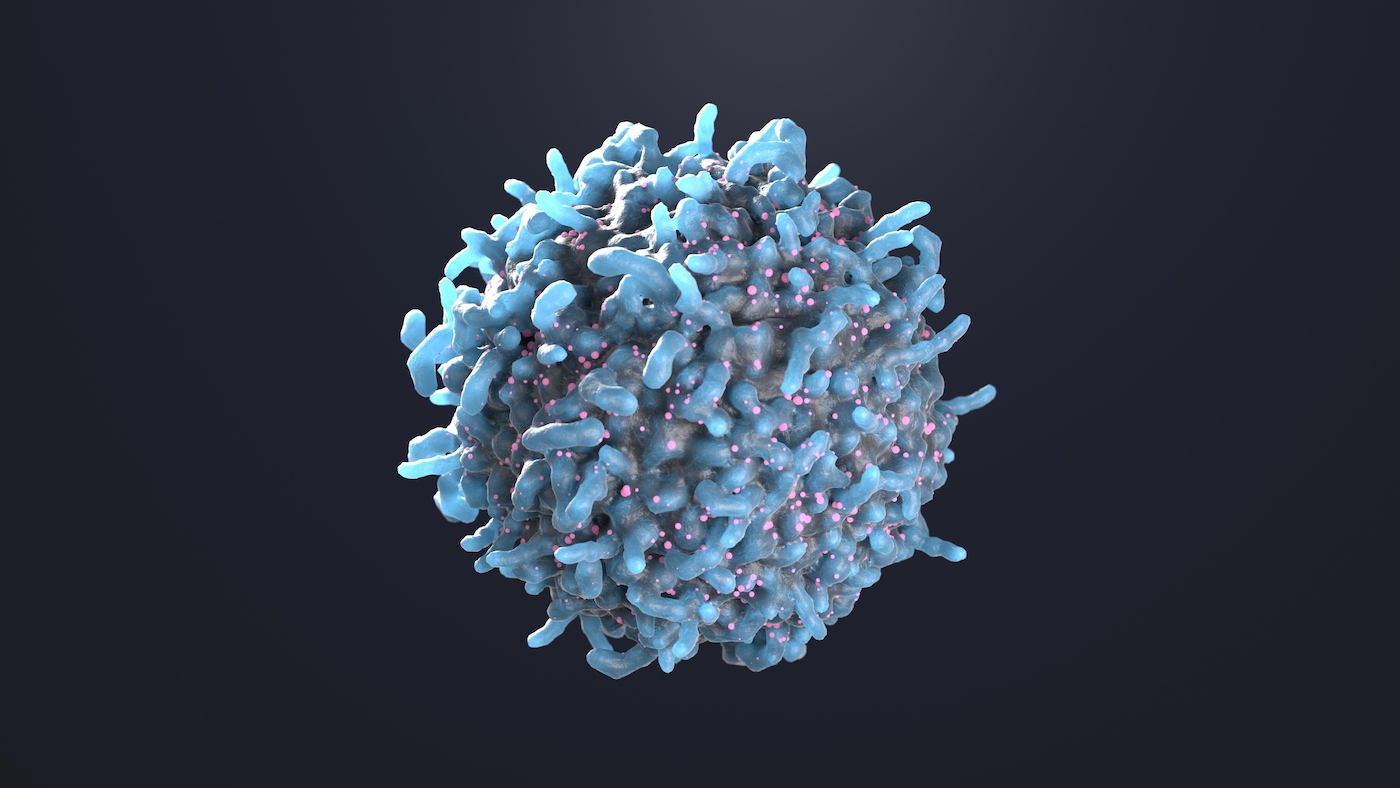

For decades, immunologists have explored CAR-T cell therapy as an effective tool to fight blood cancer. Increasingly, CAR-T cells are being explored as a potential silver bullet for treating autoimmune diseases, like lupus—which currently have no cure.

Thus far, CAR-T cell therapy has largely used CRISPR-modified immune cells from a person to treat that person’s own diseases. But new research from China has made a huge step forward for this treatment: Researchers were successful in using donated CAR-T cells from one person to treat another person’s systemic sclerosis, an autoimmune condition that causes atypical growth of connective tissues.

If donor CAR-T cell therapy does indeed work, as posited in this paper, it could mean the therapy is more scalable than it would be otherwise. Joining Ira to talk about this study and its potential impact is Daniel Baker, PhD student in the immunology lab of Dr. Carl June at the University of Pennsylvania.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Daniel Baker is a PhD student in Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, we’re going to revisit a conversation with the late Oliver Sacks about music and the brain. Plus, we’ve got a new largest prime number for all you math nerds out there.

But first, CAR T-cell therapy has been a very promising treatment for cancer. It uses the body’s own immune system to target bad cells. And there’s news from many different studies that CAR T-cells could be used effectively now to fight autoimmune diseases, too. This is a big deal because there’s no cure for many autoimmune diseases, like lupus and celiac.

A recent study out of China shows even more exciting possibilities for CAR T-cell therapy, a success from using donated cells from someone else. Wow. Can this therapy be scaled up for the millions who could benefit? Joining me is Daniel Baker, Immunology PhD student in the lab of Dr. Carl June, one of the pioneers of CAR T-cell therapy at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Welcome to Science Friday.

DANIEL BAKER: Thanks, Ira. It’s great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: All right, let’s do the ABCs. Daniel. Give us a brief reminder of how CAR T-cell therapy works.

DANIEL BAKER: Sure. So one of the wonderful things is CAR T-cells, though they can be very complicated from a manufacturing and a scalability standpoint, theoretically are very simple. Really, what we’re trying to do is we are building a synthetic receptor that’s never existed before in nature by combining the antibody domain of a B-cell with the T-cell activation domains. Essentially, the outside of that receptor lets you see your bad cell, and the inside of that receptor activates a T-cell. And so just like you said, when a CAR actually sees whatever you’re telling it to target, it activates your T-cell and lets you get rid of whatever that bad cell is.

IRA FLATOW: Wow Wow. So it could potentially be used in all kinds of diseases.

DANIEL BAKER: That’s right. While CAR T-cells have shown exceptional potential in blood cancers, one of the things the field has been percolating for a number of years is, could this same strategy, using a cell-based platform, be useful beyond cancer.

IRA FLATOW: And so now we’re seeing promising results treating autoimmune diseases. Tell us how that works. What diseases are we talking about?

DANIEL BAKER: Yeah. So diseases like systemic lupus, erythematosus, lupus nephritis, myasthenia gravis. There’s actually a whole host of diseases that we do think are B-cell mediated. But where we’re starting to see early indications of CAR T-cells actually working is in these really refractory cases where patients have been on courses of treatments, some of them for decades. And the question is, could something that is a little bit more potent than an immunosuppressive, a small molecule, or even a biologic, like a cell therapy, could that be efficacious in those contexts.

But like you’ve likely alluded to, Ira, and your listeners know, something that’s really interesting is there’s a whole host of autoimmune diseases that potentially could be targeted using the same strategy, going after bad B-cells. Right now, the field is starting in these very serious diseases where there is no alternatives. But the likelihood that this could expand elsewhere is really promising depending on the safety and efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Let’s get into some of that research because as I mentioned, there was a recent study out of China that successfully used donor CAR T-cells to treat autoimmune conditions. What was your response to reading this paper?

DANIEL BAKER: We think it’s really remarkable because something that we think about a lot in the field that is kind of troubling for us is, CAR T-cells are extremely powerful. And it’s really a new paradigm in medicine using a patient’s own cells to target disease. But one of the difficulties that we have to face as a community is if CAR T-cells started working in a whole bunch of blood cancers and a whole bunch of solid tumors and in an autoimmune disease, one of the problems we face as a field is we do not have enough capacity to treat all the patients who could potentially use this therapy.

And so one way that the cancer field has started to think about, how do we circumvent this limitation is could instead of using a patient’s own T-cells. And every single time we needed to treat a patient with CAR T-cell therapy, we would have to take T-cells from a patient and modify them in a laboratory, grow them up and send them back to the patient. What if we could just take T-cells from a healthy donor, make a giant batch of those T-cells and then infuse those into multiple patients.

And so I think the most exciting part of the study from China was, in three patients, they took donor cells from a healthy donor. They made CAR T-cells, CD19 CAR T-cells, that they modified so that it wouldn’t have graft versus host disease. And they asked the question of, if we give these to autoimmune disease patients, do we see them in graft persist and have any functional benefit.

And so really, the implications potentially is if we can get donor cells to work in an autoimmune disease setting, the likelihood that this therapy could scale out would be really remarkable.

IRA FLATOW: And did they see it work in those three patients?

DANIEL BAKER: Exactly what was so promising about this is they saw in all three patients the CAR T-cells in graft. So they looked in the blood weeks and months later, and they saw CAR T-cells there. Then the most important question is, are the CAR T-cells actually working. They said, are there B-cells? The B-cells went away for a period of time. And then they came back, the same thing that we’re seeing in other autoimmune disease contexts with autologous CAR T-cells.

And they saw improvements in all disease contexts. So the author showed that these patients showed remission for all three different diseases, or all three different patients, rather. And that’s really, really exciting. Like I mentioned, it’s still early. Six months is not a lot of time. Autoimmune disease is complicated. But it’s really promising that there’s any effects being seen using donor CAR T-cells in order to treat autoimmune disease.

IRA FLATOW: So this is really, I mean, three patients. This is really early stage. Right?

DANIEL BAKER: Yeah. You’re absolutely right.

IRA FLATOW: How do you scale this up to see if it would work?

DANIEL BAKER: Yeah, there are over 40 clinical trials that have been registered now exploring CAR T-cells in autoimmune disease. So I think very quickly, we’re going to start getting answers to what actually is the efficacy rate of CAR T-cells and what does the safety look like. So I think very quickly we will get a sense on autologous CAR T-cells because I think that’s where a lot of people are focusing. And hopefully, in the next coming years, we’ll get a sense of whether or not allogeneic, or maybe even in-vivo CAR T-cells could potentially be a therapeutic avenue for a subset of patients.

IRA FLATOW: You mentioned safety. Of course, we’re always concerned about safety first. Are there any safety drawbacks to this treatment.

DANIEL BAKER: Yeah, I think the safety concerns are the things that need to be emphasized. One of the things that we were really worried about is CAR T-cells, in cancers, have a whole profile of safety concerns that we have to be worried about, this hyperinflammatory response because your CAR T-cells are working, they’re seeing tumor, and they’re expanding.

And so when CAR T-cells first went into autoimmune disease patients, I think this is something that the field is really concerned about. Now, I think we still need to be mindful. There’s just been a smattering of case reports and case studies that have been published. So we need phase 1 phase 2 clinical trials to actually see what the safety and efficacy looks like.

But speaking broadly, these CAR T-cells in autoimmune disease look much safer than what we see in cancer. So most patients have less than grade 3 cytokine release syndrome. I know that there’s been one report of a neurotoxicity, but again, that is a much smaller safety profile than what we have seen in cancer. And so really, what is particularly exciting for us is it looks like a lot of the safety concerns are maybe a little less pronounced in an autoimmune disease setting. And that’s something that we thought might be the case.

In cancer, you have millions, billions of cells that are rapidly proliferating that you’re trying to get rid of. In autoimmune disease, you don’t have this huge target burden. And so your CAR T-cells don’t need to kill as many cells. And we thought that potentially might be the case that you wouldn’t see as strong safety effects. And that’s being borne out. And time will tell how long that is true. But we’ll see.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Any tests planned here for the US?

DANIEL BAKER: Yeah. I think there’s a number of clinical trials that people are trying to get going in the United States, I think, trying to expand this to multiple different countries. A lot of the pioneering work has been done in Germany. And as you’ve mentioned, there’s a lot of work being done in China. But I think expanding it to the United States is something that we’re really excited about doing.

IRA FLATOW: So what could this mean, then, for the future of medicine if we’re able to scale donor CAR T-cell treatments?

DANIEL BAKER: Well, at the risk of being hyperbolic, I really do think cell therapy could change everything. I think it could change medicine as a whole. It’s easy to think of CAR T-cells, and I think lots of us think of CAR-T cells as kind of an iterative next step. It’s a living drug. But I think what we have done for the first time is we have taken the fundamental unit of life, a cell, and used it to treat disease. And so the implications for cancer and for autoimmune disease now seem clear. I think that CAR T-cells and autoimmune disease definitely has a future.

But like you’ve mentioned, the host of promise for other diseases is really exciting. There’s some pioneering work that’s being done by Jon Epstein’s group here at Penn, showing that you could use CAR T-cells to go after scar tissue in the heart after a heart attack. And at least in mice, we see really, really strong and promising effects. The same thing is true with chronic diseases and senescent cells. I think really there’s a whole host of diseases that potentially could be actionable using a cell-based platform.

Using cells, we often talk about cellular therapy as a new pillar in oncology. But I think, really, what we are facing in this decade is that cellular therapy is going to be a new pillar of modern medicine. And what exactly that looks like is going to be fun to explore in the next coming years.

IRA FLATOW: Are we talking about cures here instead of treatments because I’m wondering if you think, as a young researcher in medicine, about a dilemma. We have had researchers on this show who talk about CAR T-cell therapies as being so promising they could cure diseases. And the dilemma being, is it in the interest of drug companies to cure diseases when their stockholders expect them to maximize profits, which means a cure, not a cure. But let’s have them taking drugs forever.

DANIEL BAKER: Yeah. I understand the economic implications for some of these companies, but at the end of the day, we’re trying to– I mean, they’re trying to capture value, too. And I do think that these will be cures, at least in a subset of patients. It’s clear from cancer that’s the case. Whether that will be true in autoimmune disease, only time will tell, obviously. But I do think that cellular therapy has the potential because it is a living drug, is something that could be curative in a whole host of disease settings. And I think that ultimately that could change medicine. And whether that will have implications economically, it surely will. And I think we are pretty dynamic as a society, and I think we’ll respond appropriately to the promise of a new era in medicine.

IRA FLATOW: Daniel, I thank you for taking time. This has been tremendously uplifting, I think, at a time when we need something like that.

DANIEL BAKER: Thanks, Ira. It’s been great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Daniel Baker, Immunology PhD student in the lab of Dr. Carl June, one of the pioneers of CAR T-cell therapy that’s at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.