One Step Closer To Curing Cancer

9:21 minutes

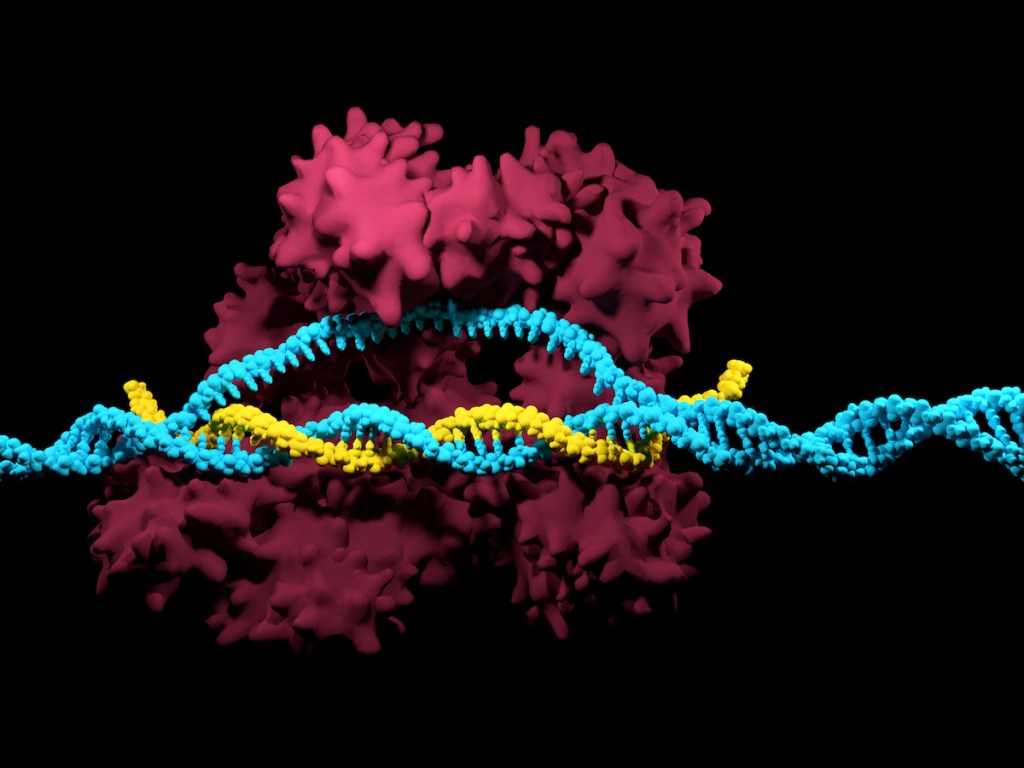

Two cancer patients treated with gene therapy a decade ago are still in remission. Thousands of patients have undergone this type of immunotherapy, called CAR-T Cell therapy, since then. But these are the first patients that doctors say have been cured by the treatment. The findings were recently published in the academic journal Nature.

Ira talks to Dr. Carl June, co-author of the study, and director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Carl June is a professor, Immunotherapy and the director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Two cancer patients treated with gene therapy a decade ago are still in remission. Thousands of patients have undergone this type of immunotherapy, called CAR-T cell therapy, but these are the first patients that doctors say have been cured by the treatment. The findings were recently published in the journal Nature. Joining me now is Dr. Carl June, co-author of the study and director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Dr. June, welcome to Science Friday.

CARL JUNE: Hi, Ira. Thank you very much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Now, you’ve said that two patients in the study were cured of their leukemia. And I know most doctors are wary of using the word “cure” in the same sentence as cancer. What makes you so confident about this?

CARL JUNE: First of all, we were very reticent to use that word and have not in previous reports of our therapies. But these were the first two treated a decade ago now. And they both had sustained remission with no further treatment. So we know from the natural history of leukemia, when patients are cured with other therapies, that if it doesn’t recur within a few years, the patient usually will never have that tumor come back. This doesn’t give people immortality, but what it means is that they have aged now for 10 years with no further leukemia.

IRA FLATOW: That’s amazing. I know these patients underwent something called CAR-T cell therapy. And this involves taking cells from the patients, and do what with them?

CARL JUNE: Yeah, so as you mentioned at the top of the show, it’s a form of gene therapy. And more precisely, cell and gene therapy. So the patients actually are involved in manufacturing the CAR-T cells. So they donate blood cells, the T lymphocytes, from a blood donation. And then in our laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania, they were grown for about 10 days and genetically modified so that they became killer cells for leukemia, called CAR-T cells.

And then after the manufacturing process, the cells were infused into the patient just like a blood transfusion. And then that’s it. It’s a one-time therapy.

IRA FLATOW: And what do the cells do once they get into the patient?

CARL JUNE: Well, unlike other drugs, which– like if you take aspirin or whatever, they get metabolized, and you take them recursively, over and over again. These cells actually begin to divide in the patient. So we’re able to measure them in the patient, and they expanded exponentially in the patients so that one CAR-T cell became 1,000 in the patient. And inversely, at the same time, their tumors, which were in these two patients between 3 and 7 pounds of tumor at the time we treated them, the tumor became undetectable as the CAR-T cells divided and killed the tumor cells.

IRA FLATOW: And so the patients still have their CAR-T cells 10 years later?

CARL JUNE: Yeah, that was a major surprise. You’re exactly right. Both patients continue to have CAR-T cells on patrol. We could remove them. The patients kindly donated more blood samples. And we could find the CAR-T cells in their blood and then, in the laboratory, exposed those CAR-T cells to leukemia again. And the CAR-T cells promptly killed the leukemia cells. So they stay on patrol in a form of immune surveillance.

IRA FLATOW: You used the word amazing. Are you still amazed by this?

CARL JUNE: Well, yes. So first of all, I’ve never said the word “cure” before, because we didn’t have that data. And now, at least in these first two patients, we have very mature follow-up data. And then, secondly, we were– in the actual trial, we infused these cells, and the informed consent document– we thought, based on our mouse studies, that the cells would only persist a few weeks in the patient and that they would go away. And so it was a major surprise that these cells can literally take foothold and survive for a decade in the patients.

IRA FLATOW: Do you know why that happens?

CARL JUNE: Well, we have some really good hints. And it was a major surprise because the body wasn’t able to reject these gene-modified cells that had, for instance, now some mouse proteins in them. The antibody that’s in these T cells– which is where the word chimeric comes from, the Greek fusion of two different species of animals– in this case, the CAR-T cells are a fusion between a B cell and a T cell in our immune system. And because part of that came from a mouse, we thought the human immune system would, within a few weeks, reject those cells and they would disappear. But we found out that there’s a process called immune tolerance and that the body was educated and was unable to reject these cells that now are chimeric and have a mouse protein in them.

IRA FLATOW: Now, why do so many other patients not have such success that you’ve had with these two patients?

CARL JUNE: Well, so these were the first two patients. And what we found– and now there’s hundreds of groups doing this. Back in 2010, it was only a handful of academic centers. But now, with thousands of patients treated, we know that with these kinds of CAR-T cells, the response rate depends on the cancer.

So if it’s acute leukemia, 80% or 90% of the patients go into long-term remissions. In the patients that we just described, they had chronic leukemia, and there the success rate is about 30%. And it just so happened the first two patients we treated are long-term– these long-term responders.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any way to tweak what you’re doing and maybe get more of the chronic cases?

CARL JUNE: Well, that’s the $64,000 question. We have data now, and there are several centers that, if we combine this therapy with a small molecule compound called ibrutinib, we can now get in chronic leukemia like this an 80% or 90% remission rate. So that’s on the horizon, which is like all kind of– most cancer therapy. It’s combinations of different therapies are required to get long-term care. So we think that’s going to be the pathway for that form of chronic leukemia.

IRA FLATOW: Now what about solid cancers, which make up the vast majority of cancer cases? Do you think that there’s some hope for this kind of technology?

CARL JUNE: Yeah, well, that’s clearly the major issue. 90% of all cancer in the US– and across the world, really– is solid cancer. And about 600,000 patients a year, I mean, in the US, die alone. And we have this conundrum where there’s very promising data in a lot of mouse experiments in solid tumors, with various cell and gene therapies, but it’s been disappointing so far on clinical trials. And this is where we need more research. So I’m hopeful that we’re going to solve that problem over the next decade, the field will. There’s now so much research in progress that hopefully will build on these initial steps in blood cancer.

IRA FLATOW: You know, when people hear this, people who are suffering from leukemia hear this, they’re going to want to say, hey, how do I get in on that?

CARL JUNE: Well, fortunately, you know, this therapy is now FDA approved. That happened in August of 2017, initially for pediatric and young adult leukemia. There’s many different trials now open across the world, but particularly here in the US for all kinds of blood cancer. And in some cases, they’re FDA approved. And others, they’re still research trials.

Like all early technologies, it takes some time to go into community hospital centers. So mostly, the initial research is at major cancer centers. And this is active all across the country now.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I know you’ve been developing cancer immunotherapy, what, for 25 years? How much of a milestone do you think these recent findings are?

CARL JUNE: Well, I think it’s great news for the field, because it says that these cells can be safe and do what we wanted them to be, you know, serial killer cells in the patient to kill cancer. So that’s now proven in these initial patients. Whenever you have, and talk about, things like gene therapy, the big worry always is, is it going to turn the cell into some kind of Frankenstein-like cell, you know, that would be uncontrolled and so on? And what these two patients teach us is the cells behave exactly as we had hoped. They stay as leukemia killer cells, have not caused any side effects in these patients to term.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we wish you good luck to you and your patients. It’s wonderful that we have some really good news to talk about sometimes.

CARL JUNE: Yeah, so much. And I want to really thank our initial patients who volunteered for this and for the large team of scientists and clinicians at the University of Pennsylvania that made this possible.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Carl June, co-author of the study and director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.