Can You Fidget Away Your Anxiety?

4:20 minutes

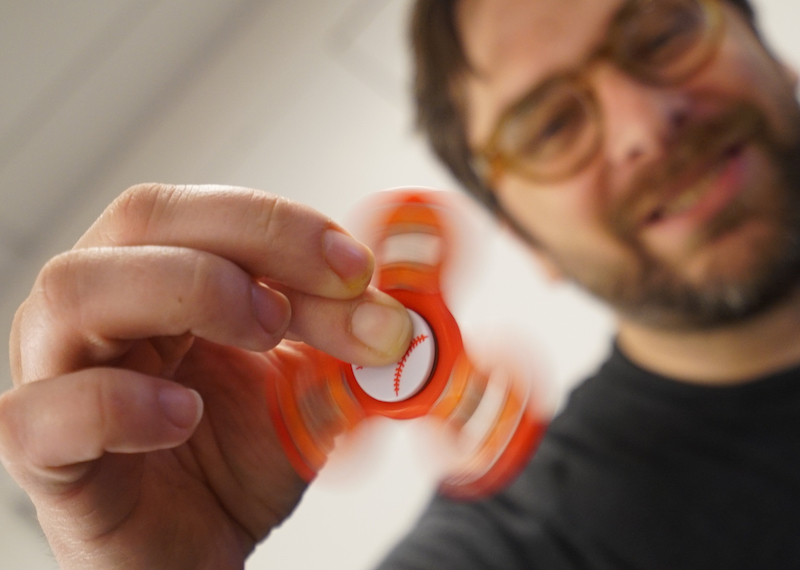

Have you gotten your hands on a fidget spinner yet?

The brightly colored device can be spun, flipped and even tossed in one hand, and it’s been turning up in schools across the country.Manufacturers say the fidget spinners can help relieve stress, but the toys have already been banned as distractions in some classrooms, sending kids back to the Stone Age of clicking pens and squeezing stress balls.

Katherine Isbister, a game- and human-computer-interaction researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, says there’s a reason we fidget: It’s a “kinesthetic, tactile” activity that can help us think.

“There’s research, actually, that moving your hands around can help your brain perform a little better,” she says. “So, it’s something everyone does, and it’s really not necessarily a problem, provided that it doesn’t get distracting, of course.”

Isbister has studied fidget objects for years and recently wrote an article for The Conversation about how the toys can help some people stay focused. She sees a different problem with the new fidget spinners, however: They take too much focus.

“Some fidgets are the kind of thing you can just keep quietly in your own hand,” she says. “So, you think about something like a stress ball, or a worry stone, or there was a recent craze for this putty that all the kids had. And those things you can use without having to look at them.”

Fidget spinners, however, require some concentration to get going — especially the tricks that “kids are really impressed by,” she says. “So, of course, not only does that get the kid looking at the spinner, but it also gets everyone else in the classroom looking at the spinner, which isn’t exactly great for the teacher.”

[Measure the rotational speed of a toy.]

Isbister herself is working on the next generation of devices: “smart fidgets” that can help us learn more about our fidgeting habits. She explains that after one of her students, Mike Karlesky, became interested in why people fidgeted as they worked, “we realized that most computer devices have taken a lot of the nice, fidgetable qualities out of how they’re designed.”

“So, we’re actually trying to make smart fidgets,” she says, “to build back those interesting kinesthetic qualities into objects that you fidget with, but that also can, for example, capture traces of how you’re fidgeting — to help you keep track a little better of when you fidget.”

And, as researchers learn more about the science behind fidgeting, keep an eye out for more fidget toys in classrooms — hopefully, ones that lend more focus than they take.

“I think as people have started to understand better the link between good thinking and body movement,” Isbister says, “it’s become much more sensible and common sense, even among teachers in elementary schools, that kids do need to move around a little bit to think well.”

Katherine Isbister is a professor of Computational Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is also the author of How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design (MIT Press, 2016).

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to play good thing bad thing.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Because every story has a flip side. Now you may have noticed people walking down the street fixated on a little device in their hand. Right? And no, I’m not talking about a smartphone. I’m talking about fidget spinners. Do you have one? I’ll bet you do. You can spin, can flip, or even toss these brightly colored cloverleaf devices. Say that quickly. They’re supposed to help alleviate stress, but they’ve been banned in some classrooms by teachers, because they’ve become a distraction. What happened to stress balls or those repeated pen clicks? Remember? No.

Well, my next guest is here to tell us the good and bad of these fidget widgets. Katherine Isbister is professor of computational media, at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Welcome to Science Friday.

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Oh, thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: So fidgeting is a very specific behavior. So what characterizes fidgeting, for example, from other movements or behaviors?

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Yes. So I guess how we think about fidgeting is it’s moving something around in your hands or sometimes fidgeting with your body when you’re doing something else. So when you’re in a meeting, when you’re talking with someone, when you’re trying to study. So it’s an activity that happens alongside other things you’re doing.

IRA FLATOW: And so it’s a good thing that we all have something to play with while we’re thinking about stuff?

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Yeah, sure. I mean there’s research actually that moving your hands around can actually help your brain perform a little better. So it’s something everyone does and it’s really not necessarily a problem, provided that it doesn’t get distracting of course.

IRA FLATOW: And I guess that’s the downside that people are saying about this fidget spinner– is that it is distracting, especially in a classroom.

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Yeah, well, so some fidgets are the kind of thing you can just keep quietly in your own hand. So you think about something like a stress ball, or a worry stone, or there was a recent craze for this putty that all the kids had. And those things you can use without having to look at them. But the thing about the fidget spinner is that you have to look at it to get it going, to get it spinning. And a lot of the tricks that the kids are really impressed by, have to do with balancing the spinner. So of course, not only does that get the kid looking at the spinner, but it also gets everyone else in the classroom looking at the spinner, which isn’t exactly so great for the teacher.

IRA FLATOW: I’ve played with one of these and I don’t see it– maybe it’s me– I don’t see it as something for fidgeting. It’s more like a toy than something– fidgeting you don’t look at the thing, you just fidget with it.

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Exactly. Exactly. I think that oftentimes fidgets are pleasing to look at, but you don’t have to look at them in order for them to do their work for you. I think mostly, I would say, fidgeting is more of a kinesthetic tactile thing. Something to do with the connection between the hands and the brain, rather than the eyes, the hands, and the brain.

IRA FLATOW: You have studied fidget widgets in the past. What are you interested in finding out about that?

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Yeah, so actually my student, Mike Karlesky, got really interested in why people fidgeted while they worked. And we realized that most computer devices have taken a lot of the nice fidgetable qualities out of how they’re designed. So we’re actually trying to make smart fidgets, to build back those interesting kinesthetic qualities into objects that you fidget with. But that also can, for example, capture traces of how you’re fidgeting, to help you keep track a little better of when you fidget. Maybe think about why and think about how to manage how you do your work every day even better.

IRA FLATOW: You used to get stigmatized for fidgeting. People would say oh, no– look, don’t– stop it– your mother would hit, slap your hand– that sort of thing. But now that’s turned around.

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Yeah, exactly. Well, I think as people have started to understand better the link between good thinking and body movement, it’s become much more sensible and common sense really. Even among teachers in elementary schools, that kids do need to move around a little bit to think well.

IRA FLATOW: Katherine, thank you very much. Always a pleasure to have you.

KATHERINE ISBISTER: Yeah, you’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Happy fidgeting. Have a happy weekend, while you’re fidgeting. Katherine Isbister, professor of computational media, University of California Santa Cruz.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.