Bringing California’s Groundwater Into Balance

3:41 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Kerry Klein originally appeared on KVPR.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Kerry Klein originally appeared on KVPR.

Dennis Hutson’s rows of alfalfa, melons, okra and black-eyed peas are an oasis of green in the dry terrain of Allensworth, an unincorporated community in rural Tulare County. Hutson, currently cultivating on 60 acres, has a vision for many more fields bustling with jobs. “This community will forever be impoverished and viewed by the county as a hamlet,” he says, “unless something happens that can create an economic base. That’s what I’m trying to do.”

While he scours his field for slender pods of ripe okra, three workers, community members he calls “helpers,” mind the irrigation station: 500-gallon water tanks and gurgling ponds at the head of each row, all fed by a 720-foot-deep groundwater well.

Just like for any grower, managing water is a daily task for Hutson and his helpers. That’s why he’s concerned about what could happen under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, the state’s overhaul of groundwater regulations. Among other goals, the law sets out to eliminate the estimated 1.8 million acre-feet in annual deficit the state racks up each year by pumping more water out of underground aquifers than it can replenish.

Hutson worries small farmers may not have the resources to adapt to the potentially strict water allocations and cutbacks that might be coming. Their livelihoods and identities may be at stake. “You grow things a certain way, and then all of a sudden you don’t have access to as much water as you would like in order to grow what you grow,” he says, “and now you’re kind of out of sorts.”

The Public Policy Institute of California has warned that in even in the best of circumstances, half a million acres of ag land in the Valley could be fallowed as SGMA rolls out. In the race for which land goes first—and who gets a voice in that decision—Hutson is wary of being pitted against bigger ag. “People will be fighting over water,” he says. “We may not be physically fighting, but we’re fighting over water. And it’s going to get worse.”

Chong Ge Xiong shares Hutson’s concerns. A Hmong farmer and former refugee on 40 acres in West Fresno, he supplies farmers’ markets and Asian grocery stores with bok choy, Daikon radish, sugar snap peas and other specialty crops. “As small farmers, we can’t really say what we grow,” he says through an interpreter. “We grow kind of everything.”

But this land lined with green leafy vegetables and tall stalks of sticky rice doesn’t actually belong to Xiong. It’s a lease. On one of the plots he owns, a well ran dry three years ago and he hasn’t been able to afford a new one. Today, Xiong uses those 20 dusty acres as a parking lot for his delivery vehicles. Leasing is a temporary solution, Xiong says, and he worries about more water setbacks. Unlike bigger outfits, he doesn’t have a team of accountants or lawyers to keep on top of finances and the state’s ever-changing water policies. “In one sense, you are in a different class in terms of agricultural practice,” he says.

SGMA is supposed to be creating groundwater solutions that work for everyone. But Xiong, Hutson and many others worry small farmers in particular aren’t being engaged in the decision-making process. “Often times it is the big farmers who has their representation and their voices heard,” says Dao Lor of the Fresno-based non-profit Asian Business Institute and Resource Center, which represents business owners like Xiong. “And there’s a saying: If you’re not on the table, you’re probably on the menu.”

Fears about SGMA leadership are not entirely unfounded. The 300-odd local agencies writing up groundwater plans, called groundwater sustainability agencies, or GSAs, appoint boards of directors, and a scientific article currently under review by researchers at the UC Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior paints a stark picture of who sits on those boards: “At a very high level, we’ve basically seen that there is no representation of small farmers on most of these boards,” says Jessica Rudnick, one of the study’s coauthors.

Some boards do reserve seats specifically for agricultural interests. In some cases, Rudnick says, “that ag representative’s seat might be fairly widely encompassing all different types of agriculture in the region, and so some of those actors have the potential to represent small farmer needs.” Those seats are often reserved for regional irrigation districts, however, which tend to serve larger ag interests. Otherwise, GSA board members most commonly represent cities and counties.

Yet small farmers represent more than 80 percent of California’s agricultural producers, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which defines them as producers bringing in less than $250,000 in annual income. Many of those growers are minorities. In the San Joaquin Valley, one-sixth of producers are Hispanic, and nearly one in 10 are Asian. “In the old country, ag is what we’re known for,” says Blong Xiong, executive director of the Asian Business Institute and Resource Center and the first Hmong American to serve on the Fresno City Council. Not related to Chong Ge Xiong, he worries that without more representation, small farmers could be the first to be hit by water cutbacks. “For our community, ag is survival,” he says.

Strategies for how to reduce groundwater reliance will vary with each GSA, but could include water allocations by acreage or income level, or water markets in which those with the means could buy out water from others. Small farmer advocates rumor that Madera County GSAs are considering water markets that would favor almonds and other cash crops over row crops, which tend to be grown in smaller operations. A representative of those GSAs could not recall that proposal specifically, though she did say it was possible board members were considering it.

Ruth Dahlquist-Willard argues that more small farmers need to be taking part in such decisions, though as a small farms advisor with the University of California Cooperative Extension, she acknowledges those growers can be harder to reach. They tend to have fewer resources than bigger outfits to leave the fields and go to meetings. Many don’t speak English, and those who lease land from far-off owners may not see policy mailings. “There’s not the social network either, what we might call social capital, where you have other chances to hang out with the people that are making the decisions,” she says. Even five years after SGMA was passed, many small farmers have still never heard of the law.

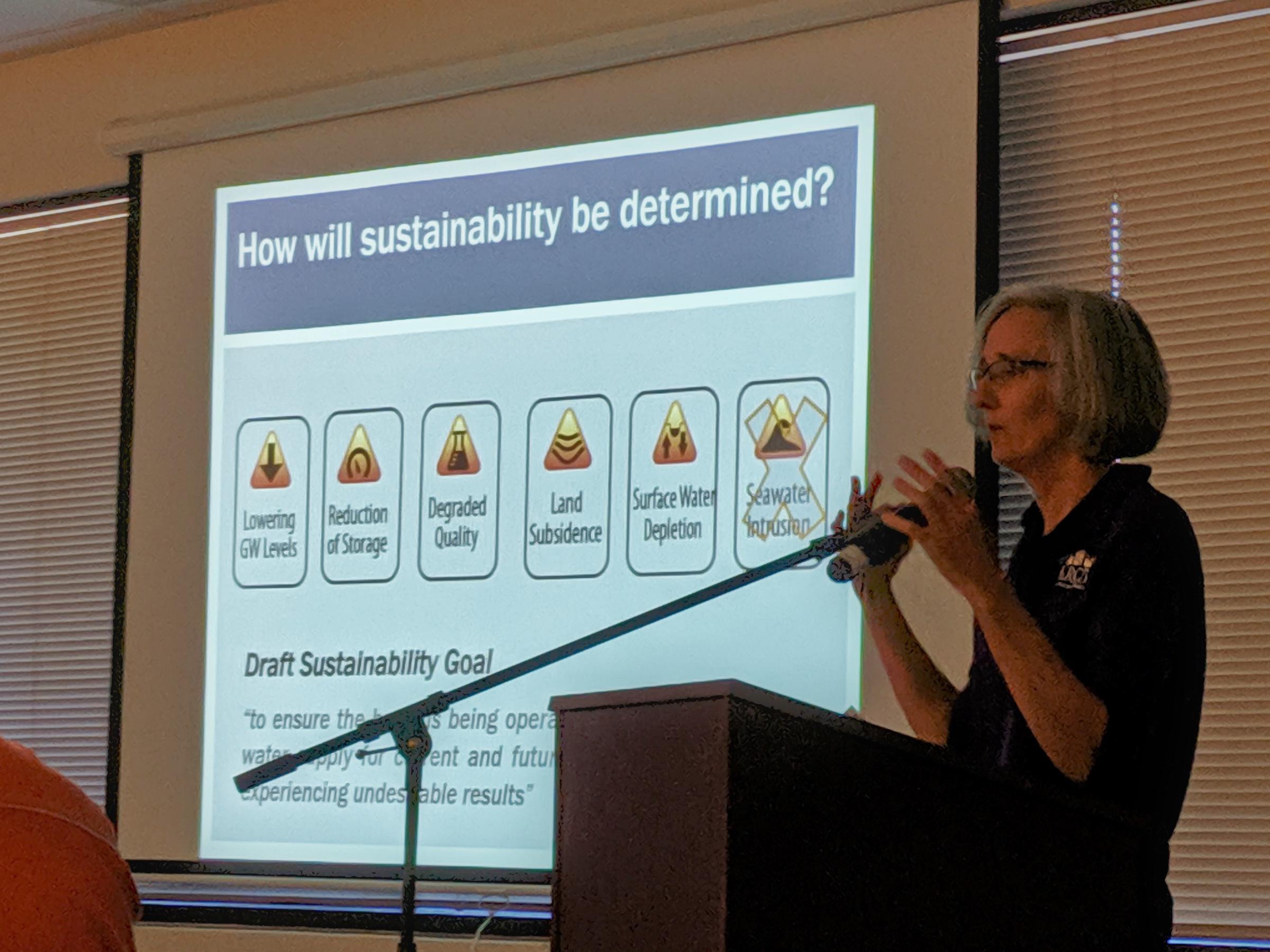

But that’s no reason not to engage, Dahlquist-Willard argues. With their Groundwater Sustainability Plans due to the state at the end of January, most GSAs in the Valley have drafted their plans and posted them to the web for public comment. “Right now is the time when farmers and anyone else who is interested can actually provide input on the plans that are going to be implemented next year,” she says.

In September, Dahlquist-Willard organized a meeting for small farmers and GSA representatives to come together in Fresno. Dennis Hutson attended; Chong Ge Xiong came out to a similar meeting for Asian business owners. “The goal was to connect the farmers with people who are putting the plans together that are going to affect how groundwater is going to be managed in the San Joaquin Valley,” she says.

Around 100 people showed up, including Gary Serrato, former executive officer of the North Kings GSA and former executive director of the Fresno Irrigation District. Among GSAs statewide, he agrees representation can be a problem. “Are there larger farmers who’re on boards as opposed to the smaller farmer? I’d say that’d probably be a fair assessment,” he says. In his Fresno County GSA, he points out that many board members are small farmers on the side, though it’s not anyone’s main job.

As for whether small farmers have more to fear from SGMA than do larger interests, Serrato says it depends on which GSA they belong to, and how much surface water can be pulled in to augment dwindling access to groundwater. For instance, the Valley’s East Side has more access to surface water than the West Side; there, bigger farmers may have an edge. “They’re the ones who’ll be able to afford to go out and buy surface water at a higher cost and bring it in,” Serrato says. “Whereas with the smaller farmers, especially crop growers, they’re better off to be on the East Side because they’re not going to be able to afford to bring that water supply in.”

Serrato says his GSA is doing its best to engage smaller farmers, and he does have a reputation for making an effort. He has reached out to advocacy groups representing small and minority farmers, and has sent thousands of mailings to landowners.

But his is just one GSA. Nearly three hundred others are grappling with the same challenges, many with less success.

Update January 2020: Since this story has been published, Madera County GSAs have received a grant from the Bureau of Reclamation to engage with disadvantaged communities and other stakeholders to develop equitable water markets.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Kerry Klein is a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California.

IRA FLATOW: And now it’s time to check in on the State of Science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO.

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio News.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. California’s Central Valley is one of the nation’s prime agricultural areas. You’ve got strawberries, leafy greens, almonds, grapes. It’s all grown there, and it all relies on water. And if you’ve seen the recent Amazon series Goliath or the classic film Chinatown, you know just how volatile water and water rights can be in the Golden State, which is why a California state law called the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act has some farmers, among others, concerned.

The law recently went into effect. And it aims to eventually bring into balance the water that goes into the state’s groundwater supplies and the water that comes out of them. Joining me now to talk about the law called SGMA is Kerry Klein, reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno. Welcome back to Science Friday.

KERRY KLEIN: Hi there, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: So give me a thumbnail, the overall point behind this bill.

KERRY KLEIN: Well, you summarized it pretty well, actually, but essentially for decades, California groundwater has been almost entirely unregulated. And in many places, the amount we use is completely unmeasured. And so the goal is to finally kind of bring some accountability to that and then bring this use into sustainability, so that we’re as close to in balance as possible, or in balance as possible, in inflow and outflow of water out of these underground aquifers.

IRA FLATOW: And so how is that planned to happen?

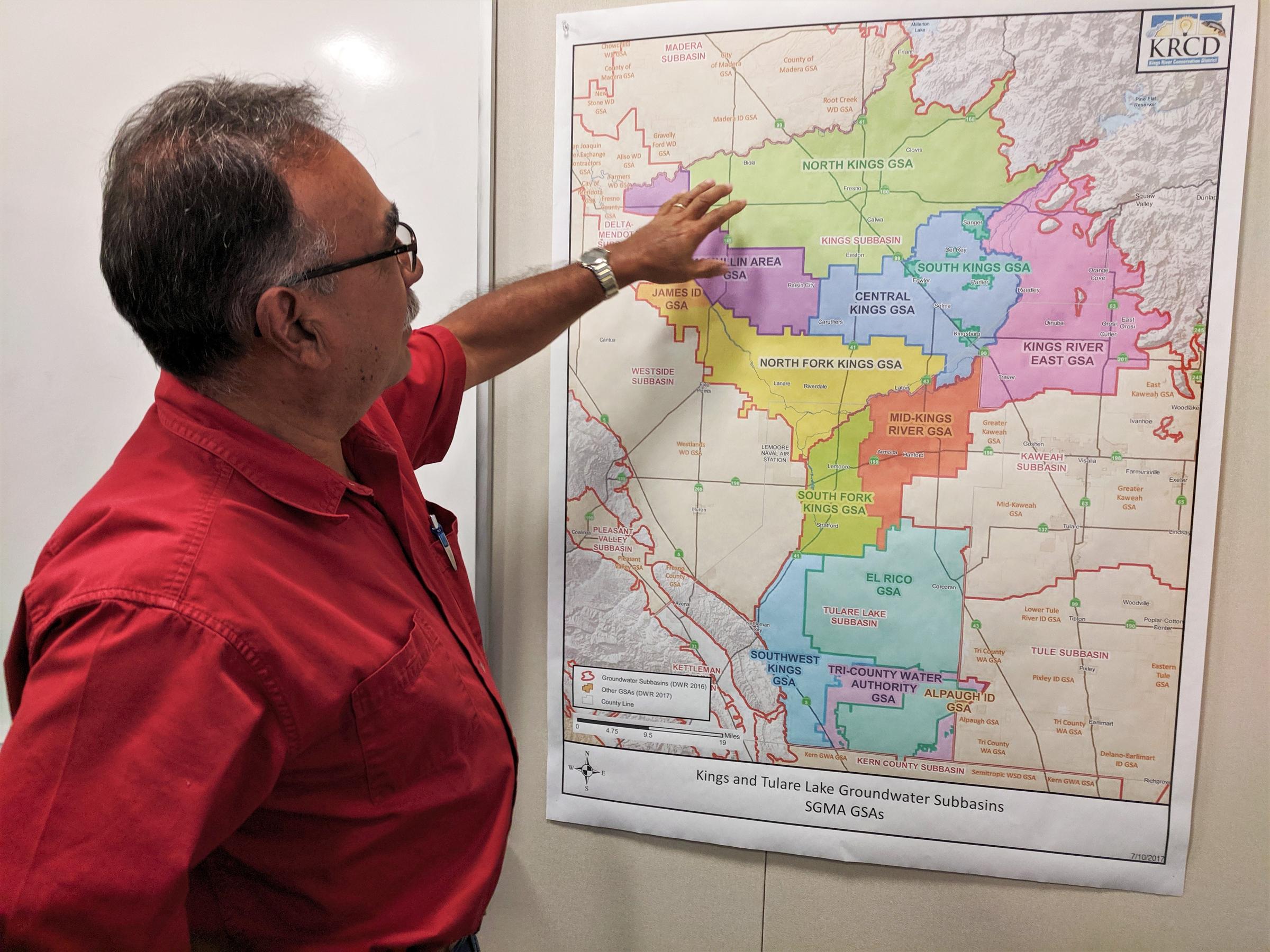

KERRY KLEIN: So it’ll take a period of a couple of decades. And it’s relatively complicated, but the state, rather than deciding on high to do– we will do such and such five steps, the state has decided to allow for kind of local control. So it divided the entire state into basins and then subbasins.

And ultimately, there are close to 300 local water agencies that got established. Most of them are run by agricultural companies, like irrigation districts. And they all get to create their own plans for how they’ll come into sustainability. And then they’ll coordinate kind of regionally to make sure they’re meeting the requirements of the law.

IRA FLATOW: So what’s the problem with the farmers? They’re upset about this?

KERRY KLEIN: Well, a lot of people are upset, the farmers, especially, because agriculture is by far the greatest water user by volume, anyway. And this will really– I mean, by all accounts, this is going to be huge for the agricultural community. And so there is one big organization that came out with an estimate that as many as– well, as many as a half a million acres could go fallow.

And that’s just in kind of one region in the San Joaquin Valley. That’s about 1/10, 10% of agricultural land that’s huge. And that’s kind of a conservative estimate, even. And so folks, yeah, they’re really concerned that their acreage will be in there and that they’ll have to do really draconian measures to reduce their water usage.

IRA FLATOW: Or would they go to sell their property?

KERRY KLEIN: Yes, and many have. There aren’t really tabulations of how many are already, but I’ve certainly met a couple of farmers who have sold their land, who are thinking about it, and even those who have been longtime family farmers for generations. But really, I mean, the worry cross cuts kind of all size farms as well, especially there are a lot of small farmers, many of whom are minorities, many of whom leased their land. So there could be impacts all around.

IRA FLATOW: All right, so we’ll have to wait and see how this shakes out, right, Kerry?

KERRY KLEIN: Yeah, absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Kerry Klein, a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California, thank you for taking the time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.