Are There Jobs In Ambitious Climate Action?

17:28 minutes

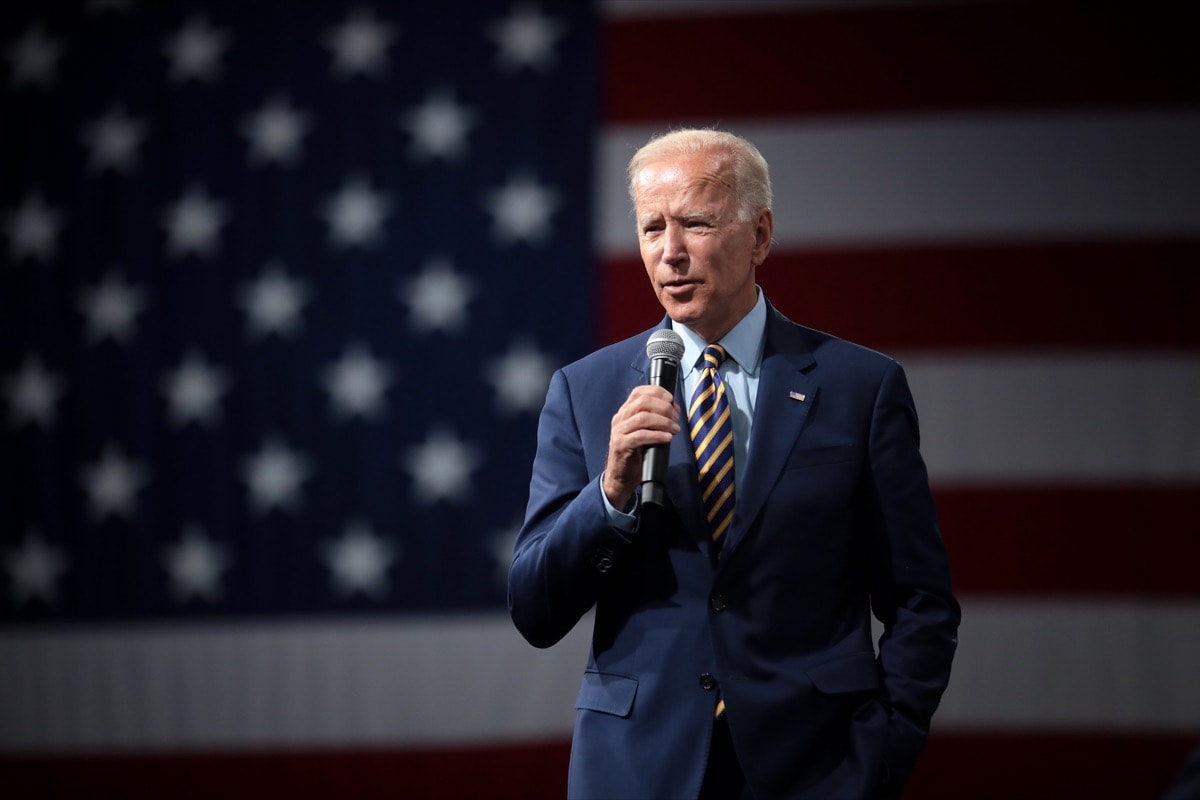

Last month, Vice President Joe Biden unveiled his plan for climate change—a sweeping $2 trillion dollar platform that aims to tighten standards for clean energy, decarbonize the electrical grid by 2035, and reach carbon neutrality for the whole country by 2050. Biden’s plan, like the Green New Deal, purports to create millions of jobs at a time when people are reeling financially from the pandemic—proposing employment opportunities including retrofitting buildings, converting electrical grids and vehicles, and otherwise transforming the country into an energy efficient, emissions-free economy.

But are the foundations of this plan on solid scientific ground? Yes, say Ira’s guests, political scientist Leah Stokes and energy systems engineer Sally Benson. Stokes and Benson run through Biden’s proposals, explaining what’s ambitious, what’s pragmatic, and what people might show up to vote for.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Leah Stokes is an associate professor of Political Science and the host of the A Matter of Degrees podcast at the University of California-Santa Barbara in Santa Barbara, California.

Sally Benson is a professor of Energy Resources Engineering and Co-Director of the Precourt Institute for Energy in the Stanford University School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences in Stanford, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

While the Democratic delegates have yet to formally vote, it seems clear that Vise President Joe Biden will contend for the presidency this fall. And earlier this month, Biden made it clear that he means to make climate change a meaningful part of his platform. This is what he said. A two trillion dollar plan that banks on millions of jobs to be found in green infrastructure, clean energy, and resilience against disaster, a zero emissions electrical grid by 2035, and a net neutral economy in its entirety by 2050. Even climate candidate Jay Inslee, whose sole campaign issue was combating climate change, is singing Biden’s praises.

JAY INSLEE: He has listened to people. He has listened to experts. He’s listened to all kinds of different parts of the country, from labor to the environmental community, to racial equity communities. And he has brought them together. And his plan is, frankly, much more ambitious and elegant and comprehensive than it might have been a year and a half ago.

IRA FLATOW: But the “if” marks a momentous set of tasks to accomplish. And if your vision of climate action involves eliminating fossil fuels entirely, there is nothing in this plan for you. Here to breakdown Biden’s plan from the pragmatic to the ambitious are my guests, Dr. Leah Stokes, assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Dr. Sally Benson, professor of energy resources engineering and co-director of the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford University’s School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Science. Welcome to the program.

LEAH STOKES: Thanks so much for having us on.

SALLY BENSON: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Leah, let me give begin with you. I keep seeing people calling this plan surprisingly ambitious. Should we be surprised after everything we’ve seen in the last few years? The rise of the Green New Deal, all these marches for climate change, the shift toward finally talking about climate in the Democratic debate. So, is this something that should logically have happened?

LEAH STOKES: Well, it’s clear that, as Governor Jay Inslee said, that Joe Biden has been listening. Since the Democratic primary ended, the campaign has been talking with lots of environmental activist groups, labor, scientists, and trying to figure out what could they commit to on climate change. And it’s hard to overstate just how bold the plan that they came up with a few weeks ago is. I mean, targeting 100% clean electricity by 2035 is what I was hoping the Biden campaign would do, but when they actually did it, I just felt thrilled. This is a really bold and exciting target. So it’s great to see the Biden campaign stepping up.

IRA FLATOW: Sally Benson, this plan is extremely ambitious when it comes to the electrical grid. Carbon free by 2035? How much of our carbon footprint does that take care of immediately?

SALLY BENSON: So that takes care of about 30% of our footprint. It’s incredibly important to decarbonize the electricity system, because that opens the door to decarbonizing residential and commercial heating. It opens the door to decarbonizing our transportation sector, particularly light duty transport. So this is really important. But if you think about 2035, on one hand, it sounds like a long time from now, but in infrastructure years, 2035 is really just a blink in the eye.

IRA FLATOW: What would it take to accomplish that goal by 2035?

SALLY BENSON: Yeah, well, one of the things that I really like about the plan is it doesn’t prescribe exactly how we do this. So it opens up the door, of course, for lots more renewable power generation. And in the United States, that’s largely going to be wind and solar. But it also keeps open the door for nuclear power, which today is the single largest source of carbon-free power. It’s valuable because we control when it’s on, unlike the wind and the sun, happens when that happens.

And it also opens the door to using technologies like carbon capture and storage, where coal plants or natural gas plants that are producing electricity can be equipped with additional equipment that will allow it to dramatically reduce emissions by about 90% or so. So literally, every single fossil fuel generating unit in the United States needs to either be converted to some other power source, like renewable generation, or we need to think about equipping it with the technology to capture and store that carbon.

IRA FLATOW: Do we have that technology yet? I mean, we keep talking about it. I know it’s being used in limited phases, in limited places, but is it ripe enough to actually capture enough carbon?

SALLY BENSON: Yeah. So carbon capture and storage is a technology that really got it started in 1996 by the Norwegians, in particular. And today, there are 19 projects around the world that are capturing and storing about 34 million tons of CO2. That’s not very much.

However, what we’re seeing around the world is the rapid interest in scale-up. The United Kingdom, Norway, we’re starting to see this in China, Australia. So it’s beginning to be used much more widely. And I guess most relevant for this particular conversation is the electricity sector putting carbon capture on electricity production. There are two plants– one in Canada and one in the United States– that are operating. And those have been up and running for about five years. Those are going fine. It’s still early days, but I think certainly the technologies available and ready to scale.

IRA FLATOW: Leah, that leads me to this. There’s nothing in here about banning fracking or transitioning away from fossil fuels entirely, things other Democratic candidates did say they wanted. Why not? Is it just too politically hot for Joe Biden to say that, since he needs Pennsylvania and some of these are fuel states?

LEAH STOKES: The fact is that a president can’t really on day one ban fracking. There were other candidates, like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, who made that campaign pledge. But it would be very difficult to implement in practice. So my thinking is that you take a lot of heat, potentially, from people who support fracking, while not necessarily even being able to deliver the goods.

I think it’s a bit unfair, though, to say that the plan does not target reducing fossil fuels or even eliminating them altogether. When you have a 2050 target for net zero across the economy, that means that we will be using no fossil fuels that emit carbon into the atmosphere. So that either means we aren’t using any fossil fuels, or we’re sequestering that carbon underground, as Dr. Benson was talking about. So I do think that this plan is about getting off of fossil fuels, even if that isn’t the explicit thing that’s named throughout the document. Because you’re right, Joe Biden has to become president before any of these climate actions can happen. And there is a lot of natural gas development in Pennsylvania. And that is potentially an important state for the Democrats to win.

IRA FLATOW: There’s also an agricultural component to this plan, biodiesel, which we’ve seen before. But also, data-driven farming, other things. Sally, how useful could this be?

SALLY BENSON: Yeah. I think we often focus our attention on the energy sector when we think about emissions that cause global warming. But in reality, the agricultural sector is a very, very significant contributor, in part due to the ongoing farming practices. But in particular, when we convert new lands into agricultural practices. So certainly, finding out a way to farm while significantly reducing emissions from the process of farming itself is going to be important.

And to the extent that we can provide fuels for transportation, for airplanes, for example, that we can provide fuels for heavy duty trucking, that will be incredibly important for decarbonizing. What we often call, too, as the hard to abate sectors, which would be things like planes and ships and heavy duty trucking.

IRA FLATOW: Leah, what about this infrastructure component? I know people who were talking about the Green New Deal were saying, if you’re going to have a Green New Deal, you have to really rip up and change the infrastructure, also, in many different ways– energy efficiency, green infrastructure. Would this really make a difference in this plan?

LEAH STOKES: Yeah. The fact is that climate change requires an enormous amount of things to get done. We’ve got to remove fossil gas from homes, renovate them so that they’re more energy efficient. We’ve got to change our cars so that they’re electric vehicles. Or figure out ways to fuel them with liquid fuels that are not fossil fuel-based. So there’s a lot of work to be done.

The good news is that that means there’s a lot of jobs. The reality is that these are going to be jobs that will take place in every corner of this country. Take, for example, removing fossil gas from homes. Right now, if you’re cooking a meal or you’re heating your home, you’re probably burning natural gas or what’s called methane. And that’s a fossil fuel. And if we really want to reach this decarbonized economy, what we have to do is remove that fossil fuel from every building across this country. And that means that little companies could spring up in every state, city, county, all across the country, and that they could help people remove this fossil gas from their homes. And that could be a program that the government sponsors.

And so, when we look at the economic crisis that we are in right now, what we can also be seeing is an opportunity to be building our economy back. And that’s really what the Joe Biden campaign is emphasizing, that this is a job creation campaign. And that we can get a lot done on the climate crisis by getting people to work and upgrading our infrastructure.

And unfortunately, the United States hasn’t been investing adequately in its infrastructure for many years now. So there’s lots of work that we need to do, not only for the climate crisis, but for other things, like repairing roads and bridges. There’s a big deficit. So that means that we can create a lot of jobs.

IRA FLATOW: Biden’s point is also getting praise for including climate justice– distributing 40% of economic gains from clean energy to historically disadvantaged communities, for example. Has environmental justice ever made it to federal policy in this way, Leah?

LEAH STOKES: Well, maybe not in this exact way. There has, of course, been some focus at the federal level on environmental justice. Certainly not enough. And it’s been very heartening to see how the environmental justice movement is gaining political power. And I do think that they have a seat at the table with the Biden campaign. That 40% number was not randomly pulled out of the air. It came from campaigners working in California and New York, who have passed laws that make sure that some of the funding in these climate change programs are going to frontline communities.

The fact is that we export so much of our pollution, particularly to black neighborhoods. We know that black children are two times more likely to have asthma, because black people are living within several miles of a coal plant all across this country. So environmental justice and fixing these historic inequities is really important. And that 40% number is a huge win. And the next step, of course, is to actually get that into law.

IRA FLATOW: Sally, tell me something in this plan that you were most surprised to see.

SALLY BENSON: Well, I guess I was really pleased to see– and not terribly surprised, but a little bit surprised– that it was very inclusive of a whole suite of technologies. That it wasn’t just 100% renewable. Because I am personally of the view that it’s going to be extremely difficult to build a 100% renewable economy in the period of, say, 30 years. So I think keeping open the options for nuclear and carbon capture and storage is very important.

I guess the other surprise– and again, really, a pleasant surprise– is how comprehensive the plan is. So if we look historically at our climate action, it’s tended to be very piecemeal in that it only addressed one particular sector or it only created solutions that a small proportion of the population could take advantage of. And none of them had a path to zero. And I think what this plan does is it really puts us on the track to, with significant stick-to-it-ness and ambition, to achieve the goals.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. In case you just joined us, we’re talking with Drs. Leah Stokes and Sally Benson about what’s in Joe Biden’s climate plan and whether it can be achieved.

And of course, as you mentioned before, we were talking about, there is tremendous opportunity, if you’re building infrastructure, creating green jobs here.

SALLY BENSON: Oh, absolutely. And they’re different kinds of jobs. There are jobs basically building renewable generation facilities. There are jobs in retrofitting homes to be much more efficient. But if we think about this, this is really an amazing point in time, where we’re contemplating shifting from being a society, a global society, that relied 85% on fossil fuels to shifting to a situation where we’re going to be zero, or very close to no fossil fuels eventually.

And still, we need to provide all the energy we need. So it’s going to take a lot of new technology. And we’ve seen some of them. We see solar panels, wind turbines, lithium ion batteries. But there’s going to be much more. We’re going to have fuel cells. We’re going to have electrolysis units that produce hydrogen. And why not position the United States to be leaders in the development and manufacturing of those technologies? So I’m very excited about getting us back to the point where the critical technologies that underpin our energy system are really built here in the United States.

IRA FLATOW: And how feasible, politically feasible, is doing any of this, since we’re talking about someone who hasn’t yet been elected? And what might happen at the polls?

LEAH STOKES: Well, the polls are looking pretty bad for the incumbent President Donald Trump, and they are looking pretty good for Joe Biden. But of course, we don’t want to trust the polls too much. We got to see who actually votes. But it could be the case that the Democrats take back the Senate, retain the House, and have the White House. And under that scenario, we could finally have a window to pass ambitious climate legislation. The last time we really tried was over a decade ago, in 2009. And we have seen, just as we’ve seen in the Black Lives Matter movement, a big public opinion shift over the last couple months.

Over the last 18 months, we’ve seen a huge swing in terms of public concern on climate change. That’s for Democrats, of course, but also independents. And so, I do think that we’re looking at a lot of climate voters. And one of the concerns that the Biden campaign might have is enthusiasm. And one way that they can make sure that they have enthusiasm is by emphasizing their climate plan. I’m in my 30s. I’m a millennial, and my generation, and Gen Z behind me, cannot wait another decade to start this process of decarbonizing our economy.

IRA FLATOW: Sally, like I, you are not a millennial. What’s your take on the shifting political winds on climate change?

SALLY BENSON: I think the time has come when almost everybody has seen the impact of climate change on their own life. Whether it’s extreme weather, polar vortexes, or extreme heat, or wildfires out in the west, or flooding, or hurricanes. And I think people just see it with their own eyes. I think the time is here now. I think that Republicans and Democrats have a pragmatic approach to this. We have to get moving. And I think there is a very, very broad support. That’s not to say everybody supports this, but I think this is the time.

IRA FLATOW: That’s about all the time we have. I’d like to thank my guests, Dr. Leah Stokes, assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Dr. Sally Benson, professor of energy resources engineering and co-director of the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford University’s School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Science. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

SALLY BENSON: Thank you very much.

LEAH STOKES: Thanks so much.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.