Bangladeshi Farmers Found A Way To Save Massive Amounts Of Water

17:33 minutes

The People’s Republic of Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries on Earth, with a population of 165 million people living in an area a bit smaller than the state of Iowa. To feed all those people, farmers in Bangladesh work year-round: in addition to growing crops during the rainy monsoon season, they grow a second or even third crop during the dry season—using groundwater to irrigate, and creating a more food-secure region.

Research published in the journal Science this month found something amazing about all that groundwater. By pumping groundwater for crops in the dry season, Bangladeshi farmers were leaving space in the aquifers to recharge during the rainy monsoon season. And this space allowed the aquifers to recapture more than 20 trillion gallons of water, or twice the capacity of China’s massive Three Gorges Dam, over the last 30 years.

The researchers call this the Bengal Water Machine, evidence for a similar concept that was first proposed nearly 50 years ago called the Ganges Water Machine.

Guest host John Dankosky talks to lead author Mohammad Shamsudduha and International Water Management Institute researcher Aditi Mukherji about how this groundwater pumping benefits farmers, and the need for more data as climate change continues.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Mohammad Shamsudduha is a geoscientist & associate professor in the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction of University College London in London, United Kingdom.

Dr. Aditi Mukherji is a principal researcher in the International Water Management Institute New Delhi Office in New Delhi, India.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. The People’s Republic of Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries on Earth, with a population of 165 million people in an area a bit smaller than the state of Iowa. To feed all those people, farmers in Bangladesh work year round. Instead of just growing crops during the rainy monsoon season, they have to grow a second or even third crop during the dry season, using groundwater to irrigate and thus creating a more secure food region.

Research published in the journal Science this month found something pretty amazing about all that groundwater. Bangladeshi farmers, by pumping water for crops in the dry season, were actually leaving space in the aquifers to recharge during the rainy monsoon season. And then this space allowed the aquifers to recapture more than 20 trillion gallons of water, or twice the capacity of China’s Three Gorges Dam.

The researchers call this the Bengal Water Machine, and it’s the proof of concept that was proposed nearly 50 years ago. Here to explain more is the lead author of that research, Dr. Mohammad Shamsudduha– he’s an associate professor at the University of London’s Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, his friends and students call him Shams– and Dr. Aditi Mukherji, who’s principal researcher for the International Water Management Institute’s New Delhi office. Welcome to Science Friday.

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: Thank you, John.

ADITI MUKHERJI: Thank you, John. It’s a pleasure to be here.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’ll start with you, Mohammad. In simple terms, tell us how farmers are managing to store all of this water.

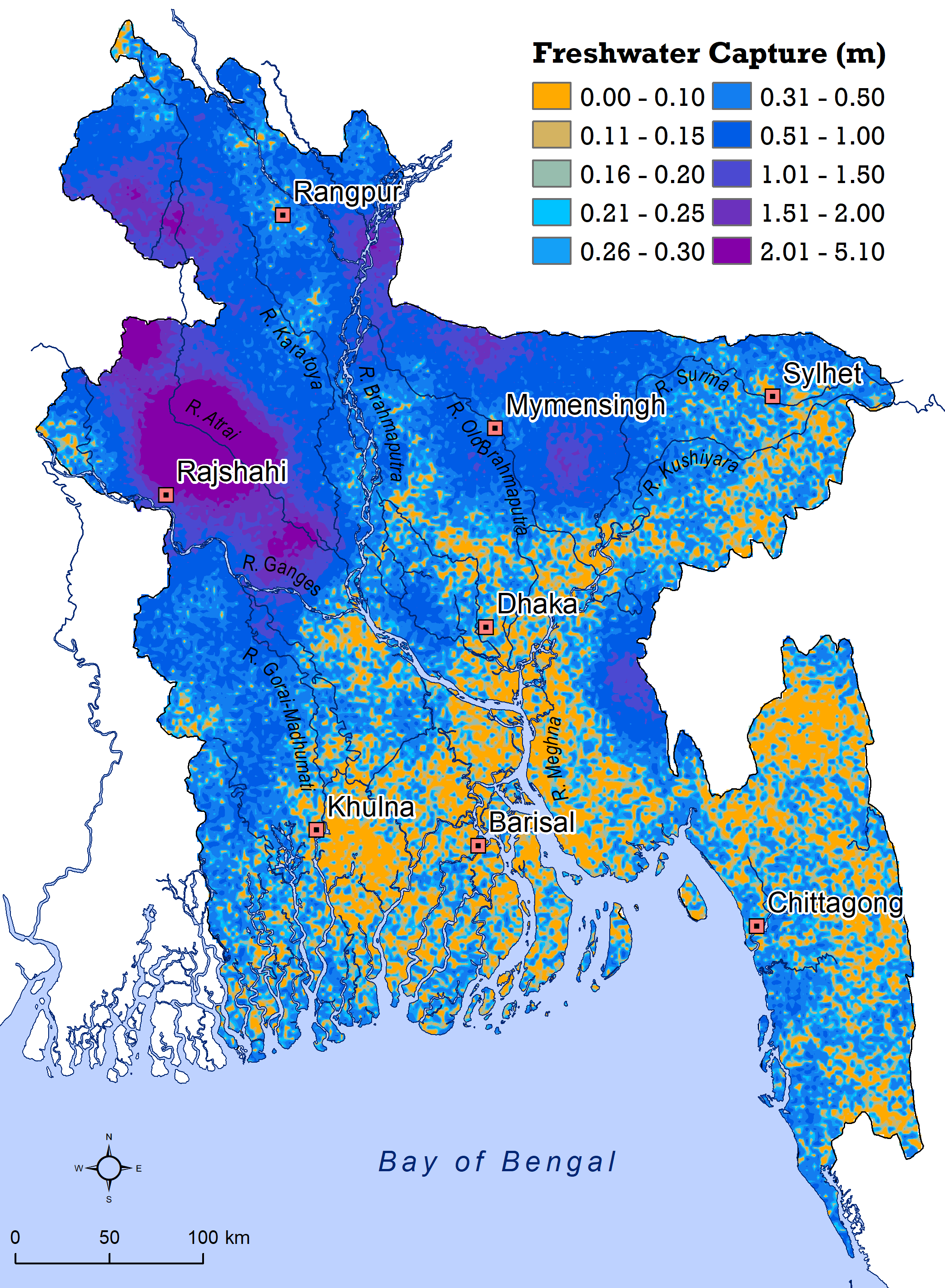

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: So the paper that we published in Science, the Bengal Water Machine is an invisible but a giant machine that operates underground in many parts of Bangladesh by millions of farmers. This water machine has been working for the past three decades and enabled capture of huge amount of freshwater from monsoon rainfall and floodwater as a result of intense pumping of groundwater to produce rice crops during the dry season.

As you mentioned, that in Bangladesh during the dry season, there isn’t much rainfall. Very little rain falls during a six-month period, which is the dry period between November and April. So farmers do use groundwater a lot.

And it started in the early ’90s, when government of Bangladesh relaxed some of the policies around importing diesel-operated pumps. So farmers started to copy each other, and they started to install shallow boreholes and to start pumping groundwater for producing rice. And the pumping of groundwater during the dry season enabled more capture of freshwater in the aquifer during the subsequent monsoon, creating this storage space and capturing of fresh water that is, as you mentioned, more than twice the size of the Three Gorges Dam in China.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So how, then, is this different from how groundwater systems might work if the farmers weren’t doing so much pumping? What would be happening instead?

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: Good question. Groundwater is found in Bangladesh at very shallow depth, so we’re talking about less than 10 meters or so below ground level in many places. Imagine there wasn’t any groundwater pumping for irrigation. Groundwater would feed to river channels during the dry season. Now, during the monsoon season, groundwater gets recharged, as you said, from the monsoon rainfall. And you see the oscillation up and down of groundwater levels in monitoring wells.

When farmers started to pump groundwater since the late ’80s, early ’90s, the seasonal dynamics suddenly changed. So dry season, water levels started to go down and down each year as farmers withdraw more and more water to produce rice crops. In the monsoon season, in many places where we have seen the operation of the Bengal Water Machine, groundwater levels rise to the pre-development condition, suggesting that the aquifers were getting more fresh water through seasonal recharge. So the very existence of the Bengal Water Machine is possible, happened, because of the intervention of millions of farmers in Bangladesh.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So let’s talk about these farmers and what they’re able to do that’s a little bit different because this machine works so well. Aditi, this number, trillions of gallons of water stored by the system– farmers can, of course, use it during the next dry season. It seems as though this is allowing farmers to do something that they just couldn’t do otherwise.

ADITI MUKHERJI: Yes. So let me say that the farmers, when they started irrigation and growing the third crop, it wasn’t necessarily that they knew that there is this particular mechanism of groundwater storage. The farmers’ original intention of using groundwater was literally to produce the food that they needed to sustain themselves and also to provide food security for the country. But because of the unique hydrogeology of the region and the very high rainfall, as Shams’ paper shows very clearly, this also turned into one of those few cases in natural sciences where it’s almost like a win-win solution.

I’m from India, and we have actually basket cases of groundwater over-exploitation. Similar things– farmers have benefited tremendously from groundwater irrigation, but it has resulted in a long-term decline in groundwater tables simply because the rainfall was insufficient to recharge all that has been extracted, or maybe because our hydrogeology was not conducive for good recharge.

So Bangladesh indeed got quite lucky in terms of these natural systems of groundwater aquifers, which are not only very conducive for the kind of recharge, but also that the very fact that they receive very high rainfall– 1,500 plus, 2,000 millimeters plus. So I find that incredibly interesting, and also very exciting that Shams’ paper actually provides proof for the hypothesis that was suggested way back in 1975, again published in Science.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, and that’s really important, though. It is very exciting. And this hypothesis goes back quite some time. It’s the first time, though, anyone’s really proven that this is working, right?

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: Yes, indeed. And the reason we were able to demonstrate that the very concept that was proposed 50 years ago in Science by Roger Revelle and V. Lakshminarayana is because of the availability of monitoring data in Bangladesh. So there are 1,250 monitoring stations all across Bangladesh that monitor weekly groundwater levels.

So we analyzed about a million data points at 465 monitoring stations all across the country. And we have seen that at about 153 boreholes, this incremental increase in dry season water levels and then filling it up during the monsoon season happened. So about a third of the borehole records that we looked at showed the operation of the Bengal Water Machine. And it was only possible because we have high-quality monitoring data on groundwater levels in Bangladesh.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And Aditi, how exciting is it to have that kind of data to be able to prove this theory?

ADITI MUKHERJI: I think it’s very, very exciting. So there have been other papers that have kind of modeled, but not actual validation because this kind of empirical study is only possible with the kind of data that Shams is mentioning, very high-density data for a long period of time. In India, for example, the central groundwater board also monitors groundwater, but they do it only four times in a year. So I think this also goes back to the importance of very good data monitoring that countries like ours needs to do to be able to understand these mechanisms in greater detail.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Mohammad, if there’s more water going into the ground thanks to this water machine, is it possible that this entire region is benefiting from less flooding than it might have otherwise seen?

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: Yes, I think it is very much possible. So what we showed in the paper is that groundwater captured more freshwater through recharge during the monsoon season. And the amount of water we are talking is 75 to 90 cubic kilometers of water over a 30-year period. So that is nearly 3 cubic kilometers of water per year, which is more than the groundwater is used here in the UK.

So that water would have otherwise flown through the rivers and would cause river flooding. We don’t have the concrete evidence, actually, to show that it has actually mitigated flooding or kind of reduced the extent of flood disasters. I think further study is needed to prove it. But there is a huge potential for flood mitigation through the operation of this water machine.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m wondering, though– as with all parts of the globe, climate change is causing so much disruption. Aditi, what are we looking at in terms of how climate change could alter these results? Are we looking at the possibility that somehow this Bengal Water Machine starts to break down because of the impacts of climate change?

ADITI MUKHERJI: I think a big unknown is what will happen to the recharge mechanism in the future. I think, to the best of my knowledge, we do not understand the recharge and the climate change situation. There is some evidence but not enough to tell us how the changes in the rainfall pattern will affect recharge.

So one of the projections for the region is that the monsoon rains are projected to intensify. We are either going to have either the same amount of rain or just more rain in the future. But the other part of the projection also says that we may have those more intense periods of rain. So basically, the same amount of rain but fewer rainfall events. So how all of those affect recharge is a bit of an unknown.

I think the other part that has got quite a close link to climate change is also the mitigation part of it. The tool that the farmers used to extract groundwater are diesel pumps. So Bangladesh currently has around 1.3 million diesel pumps. India has around 10 million diesel pumps. And these all run on diesel, obviously. And that causes a large amount of carbon emissions.

So one of the ways we have to pay attention is, how do we provide clean source of irrigation to the farmers? And here, switching these diesel pumps to solar irrigation pumps is one of those low-hanging fruits that needs to be really explored.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Are there concerns that rising sea levels, especially in a country like Bangladesh that is so close to sea level– that rising sea levels could bring more seawater into critical parts of the aquifer, that that’s one of the climate change problems with groundwater systems that you rely on in the years to come?

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: We have actually not seen the scale, the spatial scale, and the extent to which the Bengal Water Machine operates in the coastal region. It is mainly working in the northern and the north central part of Bangladesh, where there is plenty of rainfall, and it is very far away from the coast. And there is very little groundwater pumping for producing rice crops going on in the coastal area. So in that sense, there is a bit of positive side to the discovery of this water machine, that going forward under climate change, as Aditi just mentioned, it might just benefit because of the heavy monsoon precipitation may lead to more groundwater recharge. But again, we need further study to prove that.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Just a quick reminder that I’m John Dankosky, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking about the amazing capture of trillions of gallons of groundwater by farmers in Bangladesh. It’s called the Bengal Water Machine. And we’re talking with Mohammad Shamsudduha and Aditi Mukherji.

Aditi, I’m wondering if farmers in other parts of the world could benefit from this type of system. Are there are other places that you think the Bengal Water Machine could work?

ADITI MUKHERJI: So there are two things that are happening. You need a certain kind of aquifer, aquifers that are closely connected to the surface water body, kind of unconfined aquifers. And you also need a high amount of rainfall– 1,000-millimeter, 1,200-millimeter-plus rainfall. So when these two things come together, this water machine is likely to deliver in all those places.

So there are large parts of India, starting all the way from eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, where this is actually working. Same with the Nepal Terai. I mean, here we find that farmers have been withdrawing groundwater without– in many places, we do not notice, even after 20, 30 years, a steep drawdown in the water tables.

But as I said earlier, the very fact that in many parts of India, for instance, our groundwater data is limited. We do have large number of monitoring wells. But then the data is limited to only four times in a year. So that kind of makes it a bit harder to authoritatively prove this hypothesis. I think this is already working, but it will be very hard to prove it in the authoritative way that Shams and colleagues could do it with the data from Bangladesh.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’d like to ask you both, before we let you go, about what these findings can teach us about how we might manage water in the future. We talked a bit about climate change. Obviously, there are so many people around the world concerned about food security. What are some the big takeaways for you from this paper and what we’ve learned so far and how we might change our water management tactics around the world in the future?

ADITI MUKHERJI: Yes, right. So I think for me, the most important takeaways– both Shams and I have been working on groundwater for a long time. And I think you will agree with me when I say that the major worldview around groundwater is that a bit negative. It’s kind of, wherever you use groundwater, groundwater levels will decline.

And that has kind of necessarily come from studies that have been done in the more arid and semi-arid regions with limited recharge potential. You think of California, for instance, or you think of North China plains or the western part of India, Pakistan, et cetera. In all those places, we have seen intensive use of groundwater but then not commensurate recharge, simply because the rainfall isn’t adequate, leading to long-term decline in groundwater. So that has kind of shaped policymakers’ views that groundwater is always, quote unquote, “bad” and must be avoided.

But what we are seeing in this case, that we have to be very, very context specific. And in cases like Bangladesh, eastern India, and all these regions with high rainfall and alluvial aquifers, actually, groundwater can be a very powerful tool of poverty alleviation. And similar story can actually play out in Africa if we are careful about how we are managing groundwater. It can be a very successful tool for poverty alleviation as well as food security, providing, one, we are managing it properly through the correct policies, and we are also kind of investing in very good data collection and monitoring wells.

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: I just want to add that this is new knowledge. And the discovery of the Bengal Water Machine will definitely inform climate adaptation policies and groundwater pumping strategies in Bangladesh and beyond. And this finding will guide us in developing better strategies for groundwater resource management to ensure food security in the future.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Dr. Mohammad Shamsudduha is an associate professor at the University of London’s Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction. His friends and colleagues call him Shams. Thank you so much for joining us. I appreciate it.

MOHAMMAD SHAMSUDDUHA: Thank you for having me, John.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And Dr. Aditi Mukherji is a principal researcher for the International Water Management Institute’s New Delhi office. Thank you so much for your time.

ADITI MUKHERJI: Thank you, John. It was a pleasure.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.