Building Blocks Of Life Found On Asteroid Bennu

17:20 minutes

About four and a half years ago, a spacecraft called OSIRIS-REx touched down on the surface of an asteroid called Bennu. It drilled down and scooped up samples of rock and dust and, after several years of travel, delivered those samples back to Earth.

Since then, researchers around the world have been analyzing tiny bits of that asteroid dust, trying to tease out as much information as they can about what Bennu is like and where it might have come from. Two scientific papers published this week give some of the results of those experiments. Researchers found minerals that could have arisen from the drying of an icy brine, and a soup of organic molecules, including ammonia and 14 of the 20 amino acids necessary for life on Earth.

Dr. Danny Glavin and Dr. Dante Lauretta join Flora Lichtman to talk about the samples, what their analysis is revealing, and what those findings could mean for the hunt for life elsewhere in the solar system.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Danny Glavin is a senior scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and a co-investigator on the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission. He’s based in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Dr. Dante Lauretta is a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, the principal investigator of the OSIRIS REX mission, and author of The Asteroid Hunter. He’s based in Tucson, Arizona.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. About 4 and 1/2 years ago, a spacecraft called OSIRIS-REx landed on the surface of an asteroid called Bennu. It drilled down and scooped up samples of rock and dust, and after several years of travel, delivered those samples back to Earth.

Since then, researchers around the world have been analyzing tiny bits of that asteroid dust, trying to tease out as much information as they can about what Bennu is like and where it might have come from. Two scientific papers published this week give some results of those experiments.

Joining me now are doctor Danny Glavin, senior scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and co-investigator on the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission, and Dr. Dante Lauretta, planetary scientist at the University of Arizona and leader of the OSIRIS-REx mission. He’s also the author of Asteroid Hunter. Welcome to you both.

DANTE LAURETTA: Thank you. It’s great to be here.

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah.

FLORA LICHTMAN: You two know each other, I gather?

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah. Actually, Dante and I met 22 years ago, where we shared a tent in Antarctica as part of the Ansmet meteorite hunting expedition, and actually, together, discovered this rock, a meteorite from space, that had liquid water on it, which was clearly a sign of contamination. So even in the most pristine environment on Earth, meteorites can still be contaminated. And this is where the idea for OSIRIS-REx was born.

DANTE LAURETTA: Yeah, it was a really profound moment. Danny was well-known for studying a famous martian meteorite that had been found in Antarctica called Allan Hills 84001 that made quite an impact in the community when a group of scientists from NASA’s Johnson Space Center speculated that it might contain signs of life on Mars.

And he was really agitated by the water. And I remember vividly him saying, amino acids could be exchanging with the meteorite right now. It felt like finding a treasure, only to realize that it was all counterfeit. And that’s when I think we both realized, if we really want to pursue this science of understanding the origin of life and the role these carbon-rich asteroids play, we’re going to have to go out and get some ourselves.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow. So what we’re talking about today was really born 22 years ago in a tent in Antarctica.

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah. [LAUGHS]

DANTE LAURETTA: And we’ve been working together ever since.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Dante, fast forward 22 years. Remind us what Bennu is and why we wanted to go there.

DANTE LAURETTA: Bennu is a near-Earth asteroid, which means its orbit comes very close to that of the earth. And it’s somewhat infamous for being known as the most potentially hazardous asteroid. And that is not a coincidence, because when we were designing a mission to go to an asteroid and collect a sample, we needed something that was relatively close to the Earth, dynamically speaking. And Bennu has an orbit that really facilitates this kind of round trip that we went on.

But our science, and especially the science that Danny is the expert in, was going after organic molecules. And this asteroid dates back from the dawn of our solar system, over 4.5 billion years ago. And it contains a geologic record of organic molecular evolution, and it was the reason it rose to the top of our list when we were going through candidate selection for the mission target.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How much of Bennu were you able to scoop up? Like, how much mucky dust are we talking about? A pasta pot’s worth? A coffee mug’s worth?

DANNY GLAVIN: Oh, we’re talking about a cupful, 120 grams of material– which, by the way, was twice our requirement. So the science team was excited to get that much material. I know it doesn’t sound like much, but this was going to enable analyses for decades to come. It’s a bounty of material. And again, truly, this sample is the gift that will keep on giving.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, once the samples were back, what happened next? How did you start to analyze them?

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, so we took some of this sample– very small amount, a few tens of milligrams– and we basically boiled it in water. We made a Bennu tea, so we– literally– made the tea. And then we analyzed the extract using several different types of mass spectrometers to really look at the masses of the individual compounds in this tea.

And we found right away that it was this complex soup of organic molecules– incredible– almost 10,000 nitrogen bearing organic molecules. So, super complex. And among that we found 14 of the 20 protein amino acids in life on Earth, and also all five nucleobases that make up the genetic code in DNA and RNA.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Is that a big deal?

DANTE LAURETTA: It’s a very big deal. Yes.

DANNY GLAVIN: It’s a huge deal. And what makes this so important is that we’re detecting these in a pristine sample. So many of these compounds have been found before in meteorites, like the one Dante and I were looking at in Antarctica. But they’d been compromised, both from atmospheric entry heating, but also biology on the Earth.

So with the Bennu samples, they were protected from the heat during atmospheric entry. They were protected from the terrestrial biota, the biosphere. And so we can trust these results. I mean, we’re fully confident, finally, in these detections of the building blocks of life.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So this is like exactly the problem that you pointed out in Antarctica that it was counterfeit. You now do not have that problem.

DANNY GLAVIN: Correct.

DANTE LAURETTA: Yeah, that’s right. And that was really the whole motivation for the mission. And it only took us 22 years to realize that dream.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS]

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, this is definitely not a sprint. It’s not a sprint. This is a marathon.

DANTE LAURETTA: It’s a career commitment, absolutely, when you sign up for a project of this magnitude.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Was there anything in that sample that surprised you?

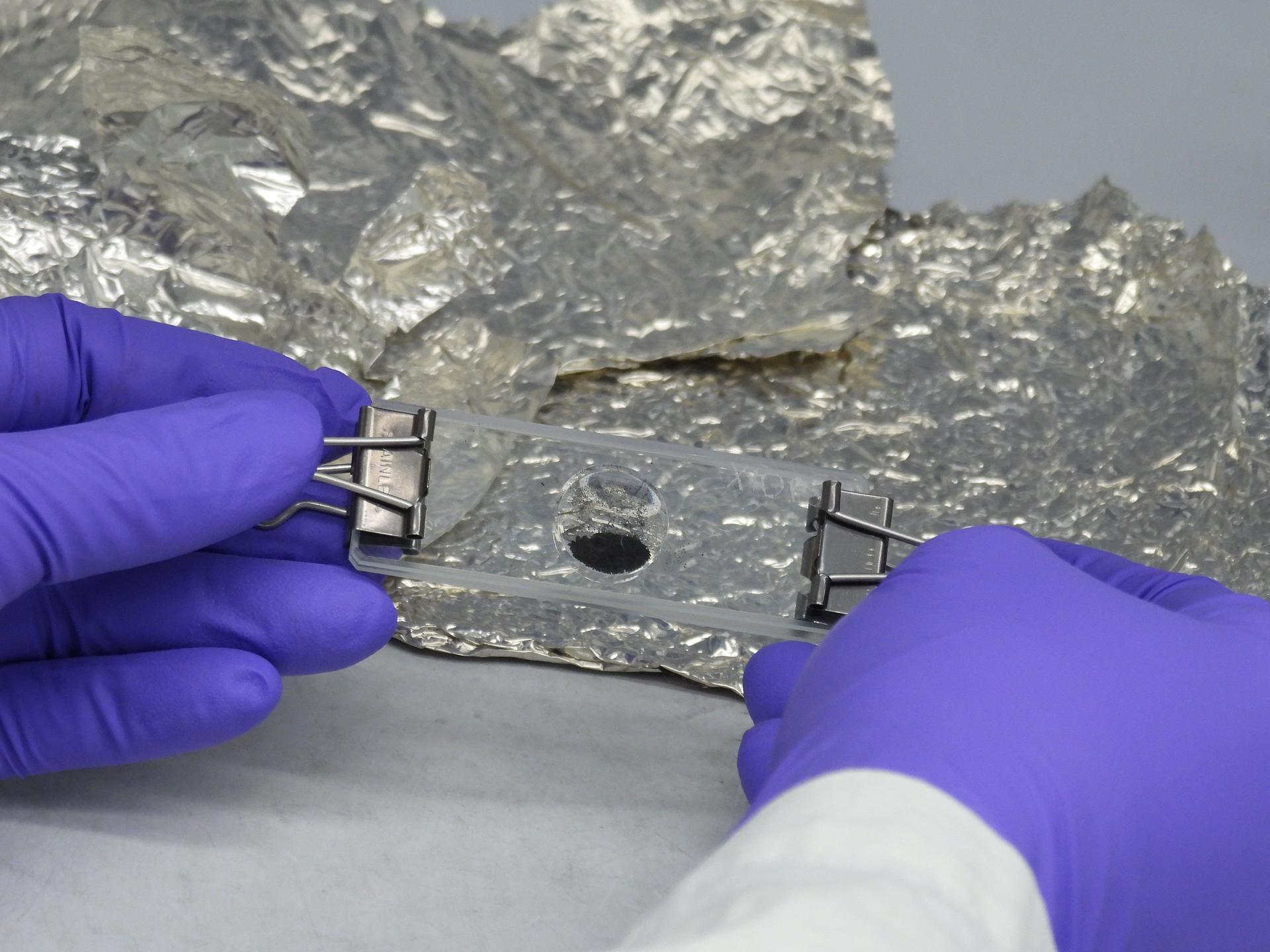

DANTE LAURETTA: Yeah, there’s several things for me. One of the things we noticed right away when we poured out the sample from the collector in the lab at Johnson Space Center, was that most of the material is really dark and black, and it’s actually hard to describe it. When you see photos of it, they’re stretched so you can see some of the contrast. But when you see it with your eye, it doesn’t look quite real. It’s so dark, it looks like a hole in the deck that it’s sitting on there.

But some of the particles are really bright and white, and they draw your eye immediately to them. And we were very excited because they look like salt. And that’s a companion paper that’s coming out in Nature, along with Danny’s organic study, is that we have evaporite minerals, minerals that formed from a large body of salty water that evaporated away and left these salt crystals behind.

And they’re beautiful crystals. They’re not just embedded in the clays. They’re growing into what looked like void spaces. So they’ve got beautiful bladed structures, the kind of thing mineral collectors dream about for their collection because they’re so stunning, just in their appearance.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What does it mean to have these salts in there?

DANTE LAURETTA: It means that Bennu came from a very wet world, and I dare to speculate maybe even something like an ocean world. We’re very interested in these objects of the outer solar system, like Europa, which is one of the moons of Jupiter, or Enceladus, which is orbiting around Saturn, because they have icy crusts with deep bodies of liquid water underneath them.

We can’t say that it’s quite that extensive of a system, but it had to be very large in spatial scale, at least kilometers across. And some of Danny’s results actually confirm that Bennu’s material must have originally formed, at least maybe as far as Saturn is orbiting today.

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, this was actually one of the big surprises, was the high amounts of ammonia. Now, ammonia is important for many biological processes as part of the nitrogen cycle. It’s volatile. And so the fact that we’re seeing such high amounts meant that this stuff had to have formed way out in a colder region of the solar system, far from the sun, where ammonia ice is stable, and also add that the ammonia was also exciting because this is an important chemical precursor, a building block, needed for the formation of amino acids and the nucleobases in DNA and RNA.

So the fact that we were seeing it in Bennu at such high levels– just to give you an idea, the amount’s about 100 times the levels of ammonia that you might find in your backyard soil. So there’s a significant amount there. And again, as Dante noted, this kind of points towards outer solar system origin of some of these ices.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Danny, any other surprises in these building blocks of life, things you did see or didn’t see, things that were unusual?

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah. So for me, the biggest kind of surprise was related to this property called handedness or chirality of amino acids. So amino acids come in two forms– left-handed and right-handed non-superimposable mirror images. So if you take a hand in your palm, and you put it palms down on top of each other, your thumbs stick out. Amino acids have that same property. And all life on Earth uses only the left-handed form in proteins, not the right-handed form. And it’s always been a mystery why that happened. Why did life turn left?

Now, we’ve been studying meteorites for decades, and we found that some meteorites, especially ones that had compositions similar to Bennu, had excesses of the left-handed form, up to 60% more than the right-handed form. And so this was kind of hinting at maybe an early solar system bias towards left-handed amino acids, which is why life turned left.

So we were expecting– I was expecting– that when we got these Bennu samples back, that we would also see these left-handed excesses. But we didn’t. They were equal mixtures of the left and right-handed form. And I remember when we were first looking at the data, I was like, oh, my god. I felt pretty discouraged, actually. I’m like, wow, this is 20 years of my research I can just flush down the toilet.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Because you’ve been working on the left-handed hypothesis?

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, we had this left-handed hypothesis. But again, this is exactly why we explore, right? This is exactly why we do missions like OSIRIS-REx so we can get closer to the truth.

DANTE LAURETTA: Yeah, and it’s also good news to me because it really convinces the team that these are not contaminations from biology.

DANNY GLAVIN: 100%.

DANTE LAURETTA: If it was biologically contaminated, it would be exclusively the left-handed versions. So we’ve done a good job of keeping the sample pristine all the way to Danny’s labs and his team’s labs to show that. So for me, it’s good news, because a big part of the challenge of the mission was preventing anything from Earth from contaminating this.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What kind of crazy precautions did you have to take to prevent the sample from being contaminated?

DANTE LAURETTA: I think the one that drove the engineering team the craziest was we prohibited them from using nylon when they were assembling the spacecraft, and they couldn’t believe the request. And we went into the clean room where they assemble these vehicles. And I don’t remember, Danny, how many different nylon components we pointed to–

DANNY GLAVIN: Oh.

DANTE LAURETTA: –and said, you got to get rid of that. You got to get rid of this. You can’t have this in the lab. You got to find an alternate. And they were like, this is crazy. How are we going to do this? And then we sat them down and we explained the science, and they got really excited. And they’re like, OK, it’s a challenge. But they were up for it. And as we’ve just shown, it’s turned out to be incredibly successful.

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, just to follow up, nylon will break down to form amino acids, which is why it was such a big concern to eliminate it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So just big picture here, does finding these building blocks of life change the way we think about how life might have evolved on Earth? Does it suggest that Bennu, or a Bennu sibling, could have brought these building blocks of life or brought life to earth? How does it impact our big picture?

DANNY GLAVIN: I mean, absolutely. I think what we’re finding with the Bennu samples in detecting these building blocks of life, in Bennu, It suggests that asteroids like Bennu, and other materials, could have delivered the raw ingredients necessary for the emergence of life, not only on Earth, but elsewhere. I mean, we’re also finding these things were spread across the solar system. So as we go look for life elsewhere on Mars or Enceladus or Europa, we know that these places also had these starting materials. So that’s actually very exciting.

Just to be clear, we’re not finding any evidence for biology on asteroid Bennu. We’re seeing the building blocks of life, not life itself. Now, that being said, we know from these analyses that these building blocks could be delivered to other environments– the surface of Mars, incorporated into Enceladus– and those may be environments where you could have had more complex chemical evolution that led to life. So we’ve got the ingredients, but again, no evidence of detecting actual life in the asteroid Bennu samples.

DANTE LAURETTA: Yeah, and for me, that presents a really exciting opportunity because we have, clearly, some sort of liquid water body interacting with these rocks and producing these interesting organic molecules. But the origin of life didn’t occur on Bennu’s parent body.

So what is missing? What happens that takes that rock and turns it into something that’s alive? That’s still, to me, the greatest mystery facing science today. And now we have geologic samples that we can do direct comparisons. These rocks from Bennu look a lot like rocks that are forming at the mid-ocean ridge right here on Earth, at these famous hydrothermal vents called the white smokers.

And so by doing a comparative analysis between those environments, similar really interesting carbonate-rich lakes on Earth, we can say, this system, it has no biology, and we can understand what its signatures are. Let’s compare it to something from modern Earth that’s rich in biology, and then use the difference in those two signals to start scanning the surfaces of Mars, looking at the salts on Europa and Enceladus, and saying, does it look like something that formed in the asteroid with no biology? Or does it look a little more like Earth, where we know biology is influencing the different mineral phases that are forming?

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, I mean, that’s actually a key point, Dante. I mean, these samples are providing a really important chemical baseline for non-life, right? And we call it abiotic baseline. And so as we go to Mars and bring back samples from Mars and explore Europa, Enceladus, we could be looking for different chemical signatures that might be more suggestive of biology.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This has been in the works for decades. What is it like for you all to have these findings start to roll in?

DANTE LAURETTA: Sometimes it’s hard to believe in my life and what I’ve been able to do, and how privileged I’ve been to be able to lead a program like this. And the results are surpassing my wildest dreams. So I’m just ecstatic. The team is excited. They’re working hard.

And I think for me, the most gratifying aspect is, there’s a lot of early career scientists that are just getting started. And you see the wonder in their eyes when we bring them into the laboratory and we say, hey, here’s some rocks that we collected off the surface of an asteroid. Are you interested in helping us analyze them? And they’re hooked. And I know we’ve got them, and they’re going to go off and do great things.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Danny?

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, I mean, for me, I mean, this entire day, honestly, I’ve just been pinching myself, I mean, literally. Am I living a dream? I mean, this feels like a science fiction story– all the things that had to go right with O-REx to get these samples back, the number of people that it took to make this happen.

I mean, I can’t believe we’re here, but we’re getting some incredible results, exciting results. We’re learning more about the origin of the solar system and potentially even life itself from these precious samples from Bennu.

And as Dante said, we’re going to have these for decades to come. I mean, we’ve actually frozen some of this material in a minus 80 C freezer that might be opened 50 years from now and studied using instruments that don’t even exist today. I’m so looking forward to the years to come and the new discoveries that come out of these samples.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do you think that we’ll have an answer to some of these big questions about the origin of life, the early solar system, within our lifetimes?

DANTE LAURETTA: I’m optimistic. Yeah, I think we’re getting better at searching for signs of life across our solar system, and especially with extrasolar planetary systems. I think we will find it. It has to be there. My instinct just tells me it can’t be isolated to just the Earth. And once that happens, then it’ll be a bonanza of scientific insights and investigation.

DANNY GLAVIN: Yeah, I mean, I feel the same. I mean, we’re here. We’re a living example that life’s possible. The building blocks, the puzzle pieces are everywhere. I think we just need to find the right environment, bring back the right samples. I think sample return, at least in our solar system, has to be part of this equation because we can, again, bring back these pristine materials, right, and get answers that are closer to the truth. So I’m optimistic as well that we’ll find something.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Well, I hope for many more sample returns, including one to Mars. I know that one’s hanging in the balance. And thank you both. So, so fascinating.

DANTE LAURETTA: Yeah, thank you, Flora. It’s been a real pleasure.

DANNY GLAVIN: Yes, thank you.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Dr. Danny Glavin, senior scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and a co-investigator on the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission, and Dr. Dante Lauretta, planetary scientist at the University of Arizona and leader of the OSIRIS-REx mission.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/