As the Climate Warms, What Toll Will Heatwaves Take?

11:34 minutes

In June, a heat wave in the American southwest sent the mercury soaring over 115 degrees in parts of Arizona. At least four deaths were linked to that heat wave.

Considering that 2016 is predicted to be the hottest year on record worldwide, and that last month was declared the hottest June on record in the United States, how could climate change influence the number of heat-related deaths we see?

“It is difficult to predict,” says epidemiologist Elisaveta Petkova. “If we see an unprecedented heat wave, extremely high temperatures, longer duration, we may see a substantial number of people dying.”

Petkova says past heat waves have shown that heat poses a severe threat to public health, especially in urban areas.

“There have been a lot of historical heat waves. Even in Chicago in 1995 there’s been a heat wave that took over 700 lives, so I don’t think we are protected from heat,” Petkova says.

Petkova, who is project director at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness of Columbia University in New York, wanted to find out more about the potential for heat-related public health problems in the future. So she, together with experts on climate science, demography and statistics, put together a study to try and predict different scenarios for future heat waves.

According to their most extreme scenarios, some 3,000 people could die each year from heat waves.

“We have projections about population change, how many people would live in the city. We have projections about the different climate scenarios that were used — a higher and a lower greenhouse gas emission scenario, various climate models, and also different adaptation pathways,” Petkova says.

“This specific estimate [of 3,000 people dying annually] is a combination of being exposed to the higher greenhouse gas emission scenario, having a higher population in the city, not reaching a higher level of adaptation in the future … it’s just a combination of different factors.”

Many people don’t think of heat as a health threat, but Petkova says over-exposure can be deadly.

“Heat exhaustion and heat stroke,” says Petkova. “But it is also important to remember that people with underlying health conditions may suffer from other types of diseases that are just exacerbated during the heat.”

Despite the dangers, Petkova says there are things we can do to prepare for even the worst-case scenario.

“We have to think about our cities, just making sure that we’re working toward a future where we have cities that are more resilient, cities that are more sustainable, where we really have access to various types of adaptations that make the life of people better at the same time and really help with addressing climate change,” Petkova says.

“And something that every one of us can do is, we all have elderly neighbors, we have parents, people we may think are susceptible [to heat]. … We can all just pay attention to those around us who may be at high risk and make sure that they know what they need to do to avoid such impacts.”

Elisaveta Petkova is Project Director at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness of Columbia University in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Well, it’s official. Last month, June, was the hottest June on record for the US. And with cities in the Northeast, including New York, finishing up the week of over 90 temperatures– over 90 here– it’s clear that the sizzling season is upon us.

And here, city officials have opened cooling centers. They’ve kept public pools open later and encouraged us to check on our elderly neighbors, all toward the aim of preventing hot temperatures from taking lives. And as the world continues to warm, is this going to become a greater risk? Is this the new normal?

Research from Columbia University is putting a number– or rather, a series of possible numbers– on heat, the toll that it could take on people living in New York City in the future. And under the most extreme scenario, more than 3,000 people could die each year. But under other circumstances, we may only see a few hundred. Why can’t we pick one number? Well, it all depends, my next guest says, on how hot it gets, but also our capacity to adapt.

My guest is Elisaveta Petkova. Elisaveta Petkova is the Project Director at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. She’s an author on new research in environmental health perspectives last month. Welcome to Science Friday.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Petkova, I didn’t know that Colombia had a National Center for Disaster Preparedness.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Well, we’re part of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. And our mission is to help the nation prepare, respond, and recover from various types of disasters, including natural disasters.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So let’s talk about some of the heat advisories in New York City this past week, including one today, which is going to run until 7:00 PM. Hot enough for you is was what people always say. But there are people who do not have air conditioning in big cities, right?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Yes, this is true. And heat advisories are issued in New York City when the heat index, which is a measure that includes both temperature and humidity and basically explains how hot it feels– when this heat index reaches 95 and it stays over 95 for a couple of days, I think, the city issues this heat advisory.

And it’s very important for people– especially those who are more vulnerable, such as the elderly over 65 years of age, people with underlying health conditions, such as cardiovascular respiratory– to just make sure that they have access to cool environments, they prevent any heat-related illness, and they take the appropriate measures to take care of themselves.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Petkova, are people surprised by– when heat gets to them, surprised by it?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: I think the interesting issue with heat is that it’s always been around. And people don’t think of heat as a threat. People don’t think of heat as a threat until it reaches a critical threshold where our bodies just start responding to it, and we’re unable to really– we’re unable to really have the regular thermoregulation to protect ourselves from the heat impacts. So it is very important to be prepared for such instances and know what the risks are and what the symptoms are of heat illness.

IRA FLATOW: Give us some of those symptoms.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Well, heat causes various possibly deadly heat-related illnesses, such as heat exhaustion and heatstroke due to hypothermia. But it is also important to remember, as I already said, that people with underlying health conditions may suffer from other types of diseases that are just exacerbated during the heat.

IRA FLATOW: One factor you say that could cut and avoid many deaths in the future is adaptation.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: What does that mean to adapt to heat?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Adaptation is a complex process. There are different types of adaptation. People naturally adapt to heat over the course of the summer. So in the beginning of the summer, when you have a heat wave, it tends to be more deadly as opposed to a heat wave later in the summer, because people have adapted to heat better over the course of the summer.

But also, over time, we as a society adapt to heat. So we build buildings that are more efficient. There are various types of measures that are implemented in the cities, such as cooling centers and educational programs so people know about the heat, and they take the preventative measures, and they have access to cool environments. So there are different types of adaptation.

The way we define adaptation in this study is by how much heat-related mortality has reduced over time. And how can we project how the future impacts of heat-related mortality can look like based on those adaptation trends?

IRA FLATOW: If the summer goes along and the heat stays with us, does your body actually adapt to the heat being around you?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: It depends. There are certain thresholds above which it would be difficult to adapt. And if you’re an older person who has an impaired thermal regulation, then it would be more difficult to adapt. So to some extent, we could, but it would be difficult to reach a real, complete adaptation to heat.

IRA FLATOW: When you make your projection about the extreme scenario of 3,000 people could die each year, how do you arrive at that?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: So there are a couple– what we did in this study– and it was a really very complicated inter-disciplinary approach we took. Because I’m an environmental epidemiologist by training, but we needed people with expertise in climate science, demography, and statistics to basically combine different types of projections. So we have projections about population change, how many people would live in the city. We have projections about the different climate scenarios that were used, a higher and a lower greenhouse gas emission scenario, various climate models, and also different adaptation pathways.

So this specific estimate that you’re mentioning, it’s a combination of being exposed to the higher greenhouse gas emission scenario, having a higher population in the city, not reaching a higher level of adaptation in the future, just seeing the population grow and grow more. So it’s just a combination of different factors.

But I just want to mention that what we really tried to do here is really paint a landscape of future possibilities and explore how different scenarios may impact our population so we can better prepare.

IRA FLATOW: We’re always talking about– this being New York, we’re talking about heat. It’s a heat island. The concrete, whatever, holds the heat in. Does that mean we’re overlooking rural areas where heat might be a problem too much?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Heat is a problem in rural areas as well, but urban areas are really more susceptible due to the urban heat island effect and also due to the higher concentration of vulnerable individuals in urban areas. So we have this combination of factors that just results in a greater burden of heat-related mortality.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any cure for the increasingly hot weather, or is it just global warming?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: It’s global warming. We can do things about it. We can try to stay on a lower greenhouse gas emission pathway. And I think what we can do as a society is just keep efforts– increase our efforts to ensure adaptation of our residents.

IRA FLATOW: Well, until then, if we continue and global warming continues on as it’s going, are we going to see the death toll rising as things get hotter or earth keeps heating up?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: It is difficult to predict. I think with this study, we have a better understanding of the kind of factors that influence heat-related mortality. If we see an unprecedented heat wave– extremely high temperatures, longer duration– we may see a substantial number of people dying. It is difficult to predict. There have been a lot of historical heat waves. Even in Chicago in 1995, there has been a heat wave that took over 700 lives. So I don’t think we are protected from– we just need to take the measures necessary to protect our population.

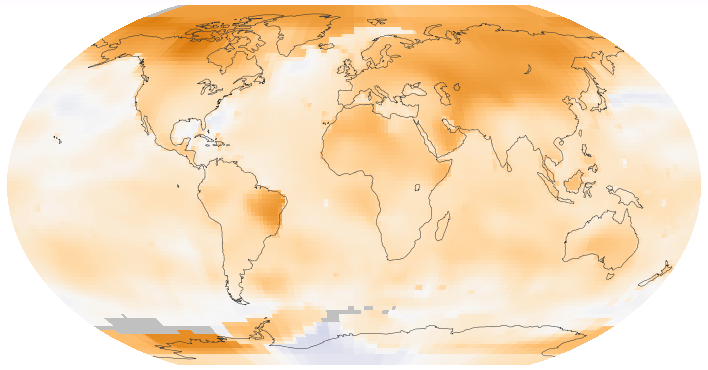

IRA FLATOW: I noticed on the heat map of Australia, which just toasts in the summertime– do they have any lessons that we can learn about adjusting or adapting?

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Yes. So this is a very good point. Because right now in the United States, we have regions, such as the Northeast and the Midwest, that are more susceptible to heat. Regions such as the South are less susceptible.

But if temperature rises and we see temperatures we’ve never seen before, maybe regions that are already better adapted, they may suffer from some additional heat-related deaths, just because it is difficult to adapt to those very high temperatures. There may be power outages. It is very difficult to predict what may happen.

So the lessons that we can learn from Australia is really the importance of heat adaptation planning, becoming more resilient as a society, and just making sure that there is a plan in place that is being implemented throughout the year.

IRA FLATOW: And I imagine tat plan is more than just getting in an air-conditioned room. It must be urban planning and the electrical infrastructure, because we see trains breaking down, subways. The rails expand, and stuff like that. So it takes a longer– much more than just getting into a cool place.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Absolutely. And I think this is the way we have to think about our cities– just making sure that we are working toward the future where we have cities that are more resilient, cities that are more sustainable, where we really have access to various types of adaptations that make the lives of people better at the same time and really help with addressing climate change.

IRA FLATOW: But in the meantime, we need to know how to recognize that we are in trouble as people getting overheated.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Absolutely. And something that every one of us can do– we all have elderly neighbors. We have parents, people we may think are susceptible. They may not realize it. So we can all just pay attention to those around us who may be at high risk and make sure that they know what they need to do to avoid such impacts.

IRA FLATOW: In this era of cell phones and things, and the internet of things, maybe there will be devices that will automatically tell us your loved one is in trouble without them having to do it themselves.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Or just check in a couple of times a day.

IRA FLATOW: What a quaint idea. Phone home, probably with a real telephone. No texting required. All right. We hope that you stay cool this summer.

ELISAVETA PETKOVA: Well, you too. And it was a real pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Dr. Elisaveta Petkova is a project director at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. She’s an author on new research in environmental health perspectives last month.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.