Should Drug Companies Stop Pursuing Amyloid In Treatments For Alzheimer’s?

17:00 minutes

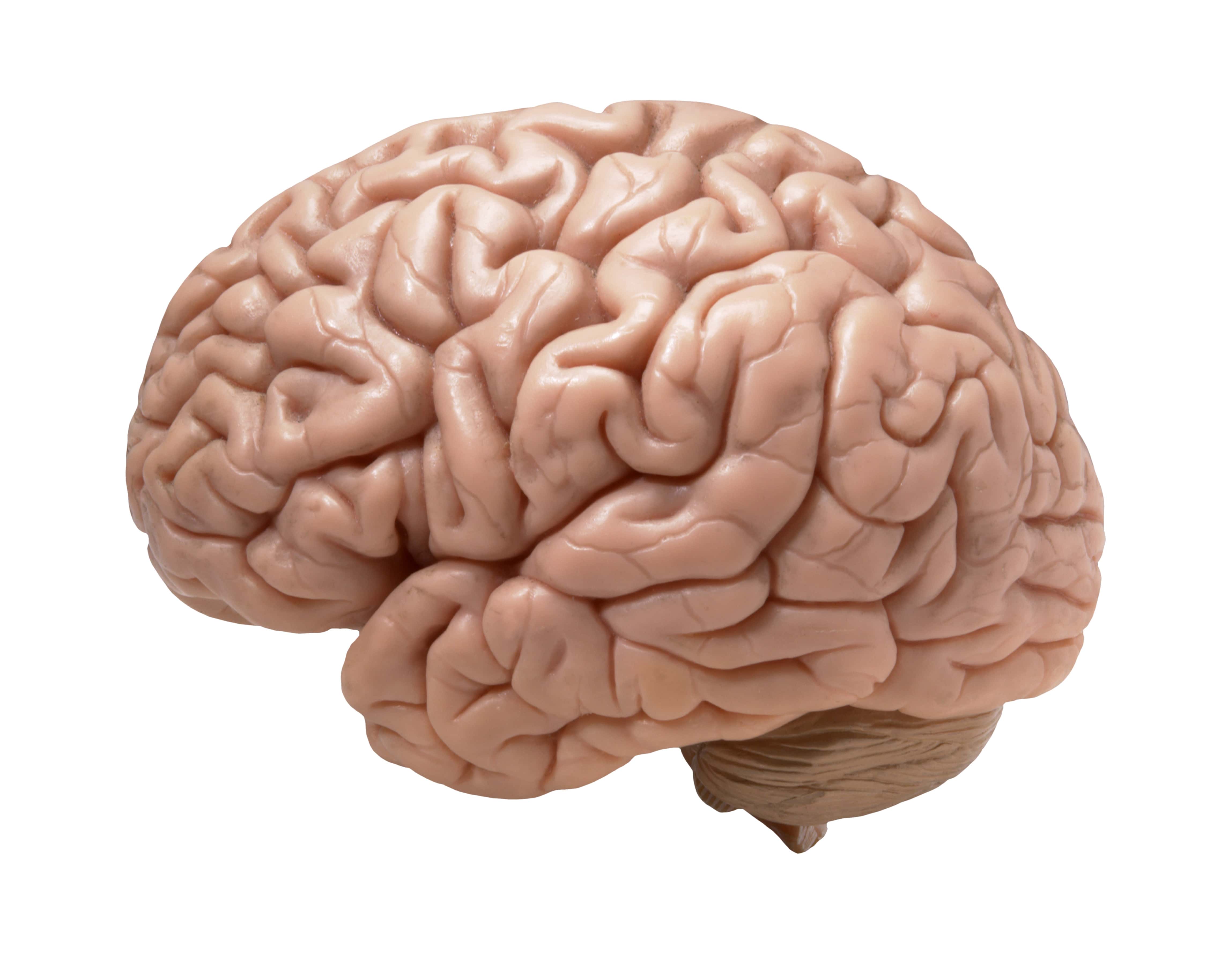

The pharmaceutical industry has been on a 30 year mission to develop a drug to treat Alzheimer’s disease. The culprits behind the disease, they thought, were the amyloid plaques that build up in the brains of these patients. For many decades removing these plaques to treat Alzheimer’s was the goal.

But then drug after drug targeting amyloid failed to improve the symptoms of Alzheimer’s—the so-called “amyloid hypothesis” wasn’t bearing out. But drug companies kept developing and testing drugs that attacked amyloid from every angle—perhaps at the expense of pursuing other avenues of treatment.

This past summer, two more high profile clinical trials of drugs to treat Alzheimer’s failed. That brings the number of successful treatments for the disease, which affects 5.8 million Americans, to zero.

George Perry, professor of biology at UT San Antonio and Derek Lowe, a drug researcher and pharmaceutical industry expert join Ira to explain what led pharmaceutical companies to doggedly pursue the amyloid hypothesis for decades, and whether or not they are ready to start trying something else.

George Perry is a Professor of Biology, University of Texas San Antonio and the Editor-in-Chief at Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Derek Lowe is a drug researcher and author for Science Magazine’s “In the Pipeline” blog.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Drug companies have been on a 30-year mission to develop a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The usual suspects behind the disease are the amyloid plaques that build up in the brains of these patients. Remove the plaques. Treat the disease. Well, for many decades, that has been the goal. And, well, it certainly hasn’t worked out that way.

Drug after drug targeting amyloid has failed to improve the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. The so-called amyloid hypothesis was not bearing out. But drug companies, they didn’t give up. They kept developing and testing drugs that attacked amyloid from every angle, even perhaps at the expense of pursuing other avenues of treatment.

This past summer, two more high profile clinical trials of drugs to treat Alzheimer’s– two more failed. That brings the number of successful treatments for the disease, which affects 5.8 million Americans, the number is zero. So are drugmakers finally ready to move on from the amyloid hypothesis? And what led pharma companies to doggedly pursue it for decades in the first place?

Here to try and help us answer those questions and to give us a sense of where the field goes from here are my next two guests, Dr. George Perry, professor of biology at the UT San Antonio and editor-in-chief of the journal Alzheimer’s Disease, welcome to Science Friday.

Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. And Derek Lowe, a drug researcher and author of Science Magazine’s “In The Pipeline” blog covering the pharmaceutical industry. Thank you for joining us, Dr. Lowe.

DEREK LOWE: I’m glad to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Perry, let me begin with you. It has been 30 years since the amyloid hypothesis was proposed. And there have really been zero successful treatments developed based on it. So how did we get there?

GEORGE PERRY: Well, when it was first proposed, the cascade hypothesis made a lot of sense based on the genetics of the disease. There are a small number of patients that have mutations that change the metabolism of amyloid and are associated with a chance of developing Alzheimer’s disease. These are mutations in the amyloid precursor protein, presenelin-1, presenelin-2. Also the fact that Alzheimer’s disease is defined by plaques and neurofibrillary tangles which are made of another protein studied extensively called tau protein.

And so the hypothesis was put forward that they were driving the disease. And also, under some circumstances, amyloid can be toxic in some culture systems. We’ve actually, with these most recent trials, really tested the hypothesis at the most rigorous degree, because we’ve actually remove the amyloid from the brain of some of the patients. And they haven’t improved at all.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Dr. Lowe, how did the drug companies get hooked on the amyloid hypothesis in the first place?

DEREK LOWE: Well, it’s true that it really has been the best looking hypothesis for many, many years. And you have to be very careful when you’re going into the field developing a drug, because Alzheimer’s is such a tough disease. You have to have a huge number of patients and dose them for years and years, because it’s so slow developing.

So you have to be ready to spend at least $500 million and probably quite a bit more if you’re going to go after it. So you have to go with the most solid looking hypothesis you can possibly find. And that’s pretty much been amyloid. There are a lot of other ideas but nothing had that foundation. That said, I think we have pretty much beaten the amyloid hypothesis as far down as it can go.

IRA FLATOW: So Dr. Perry, Dr. Lowe, where do we go? What is the next best or is there not a next best hypothesis of where to go?

GEORGE PERRY: I would like to add that we haven’t ruled out that amyloid is important in the disease. The genetics, the fact that amyloid is both there and genetically linked to it, shows that’s it’s an important element in the disease, but it may not be an important element for targeting drugs.

DEREK LOWE: That’s absolutely true. Yeah. I think when we get to the final explanation of Alzheimer’s, it’s going to have a lot about amyloid in it but there’s something more.

IRA FLATOW: So we don’t really understand the beginnings of Alzheimer’s yet?

GEORGE PERRY: You’ve got it exactly right. We don’t understand the initial phase. And that initial phase doesn’t just mean amyloid. It probably means something that is more linked to metabolism, more linked to the similarities with other chronic conditions.

DEREK LOWE: Exactly. And that’s the area that we’re going to have to be able to target with a drug. Because once the damage is done in an Alzheimer’s patient’s brain, I don’t think you’re ever really going to be able to reverse that. You have to know what the initial cause is. And we just don’t.

GEORGE PERRY: Yeah. I’m less certain about that, about the idea that the brain couldn’t repair itself to some extent if you remove the driving force.

DEREK LOWE: Oh, that would be good.

GEORGE PERRY: What we know about the brain is there’s a tremendous amount of elasticity and reconnections that happen in drastic conditions like in small strokes. Patients recover and parts of the brain is dead.

DEREK LOWE: That’s true.

GEORGE PERRY: So I would imagine if we could remove the driver, maybe people wouldn’t recover to normalcy, but they would have increased function.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Let me go to the phones, because, of course, you can imagine how many people want to talk about that. Let me go to Savannah, Georgia. Hi, Rick. Welcome to Science Friday.

RICK: Hey Ira. Thanks for having me on the show.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

RICK: When it comes to dealing with the nonfamilial form of Alzheimer’s disease, we don’t have to look any further than in nutritional epidemiology for an answer. The evidence is clear that people whose cholesterol levels are higher in their midlife have much greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

We know that oxysterols, oxidized forms of cholesterol, and AGEs that form in animal products both have integral roles in producing the Alzheimer’s pathology. When we look at people who live in the blue zones who eat a diet that’s very low in animal products, you see an almost total absence of neurodegenerative diseases like AD. I think it’s kind of an illusion for us to look at finding the answer to a problem that’s developed over a period of decades. It’s like other chronic diseases. You have to think prevention. I’d like to know what the guests on your show think about that.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Dr. Perry, any?

GEORGE PERRY: Yeah. I think this is one of the most exciting elements of Alzheimer’s disease that’s emerged in the last five to 10 years, its similarities to conditions like heart disease, which is that diet, exercise, stress reduction all make a tremendous differences in this. And of course, I like your mention about the AGEs, the advanced aging glycation products, because this is one of the things we identified in Alzheimer’s disease almost 30 years ago.

IRA FLATOW: Please tell us what that is.

GEORGE PERRY: AGEs are products of sugars reacting with proteins. They’re increased during diabetes. They’re part of the aging process. But when you have poor sugar control, such as diabetics have, sugars react with proteins and change their characteristics so they become non-functional. It plays an important role in cataract formation. It plays an important role in skin elasticity changes and connective tissue, like when you were talking earlier about the cartilage. Those type of tissues that don’t renew themselves get modified by sugars.

DEREK LOWE: There certainly is a connection between outsiders and cholesterol, because one of the only genes that we can really tie definitively to Alzheimer’s risk is called ApoE4. And it is a lipoprotein handling gene. Makes a lipoprotein. So there’s some connection there. But at the same time, all the clinical trials and real world experience with cardiovascular therapies and cholesterol lowering drugs haven’t shown that much of a connection with reducing Alzheimer’s risk. So it’s complex.

IRA FLATOW: I’m sorry, Dr. Perry. Did you want to jump in there?

GEORGE PERRY: Well, I wanted to jump in when the person was talking about the Blue Zones. Those are areas in which people are much healthier than average. Is also intervention studies such as the FINGER study, which was done in Finland. It showed that if you change diet, you can lower your risk of Alzheimer’s disease tremendously.

So lifestyle plays a tremendous role in things that you can do. Especially as mentioned earlier about cholesterol during middle age, obesity, et cetera, during middle age has a tremendous effect in your chance of having Alzheimer’s disease. And studies that show that at certain ethnic groups, African-Americans and Hispanic Americans are at higher risk of having the disease. All of this points to lifestyle being an important element.

IRA FLATOW: Well, what about inflammation? doctors talk about inflammation as being important in many diseases. I would imagine you’d have to look at that for Alzheimer’s also.

GEORGE PERRY: And inflammation is tied to things like obesity and diet, et cetera. Stress causes inflammation. But its direct linkage is still less clear just like the cholesterol linkage is there, but it’s not straightforward.

DEREK LOWE: Exactly. Inflammation is such a common process. And it’s associated with so many disease states and, indeed, sometimes with aging itself, that it’s really hard to disentangle that.

IRA FLATOW: Let me go to the phones again to– let’s go to Fort Dodge, Iowa. Greg, hi. Welcome to Science Friday.

GREG: Hi, thanks for having me. I was a couple of months ago at the Alzheimer’s Association International Research Conference out in LA. And they were talking about some of the different types of related dementias. One of the newest ones was limbic predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy. and how much that’s changing our paradigm of what Alzheimer’s disease is.

So as we learn more about what some of these related systems are, how does that change where the research is heading? And does that account for why some of the research in the past maybe wasn’t as successful, or maybe didn’t reach the endpoint is a better way to say it, than what we anticipated?

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Perry, Dr. Lowe, how related are all of the other–

DEREK LOWE: Oh. Oh. No, go ahead. I’ll let you field that one.

GEORGE PERRY: OK. Well, when you have age-related dementia, there’s many different diseases. When I started in this field in the early ’80s, there was Alzheimer’s disease and Pick’s disease, and that was pretty much it.

Since then, we’ve determined a number of different diseases that are all related. And this limbic condition has just been described as a condition of older individuals, meaning over 85 years old or so. Could that be important in the clinical trials as heterogeneity? Of course it is. But even in subgroup analysis, and I think Dr. Lowe is in a better position to be able to comment on this, there wasn’t a miraculous cure for any of the groups that have been analyzed.

DEREK LOWE: No. That’s absolutely true. People have gone over the clinical data looking for some sort of group that looked more likely to have benefited from any of the treatments has been futile. Eli Lilly spent a really inordinate amount of money going back with one of their outsiders amyloid antibodies and doing the whole trial again in what they thought was a more likely group. And nothing worked.

IRA FLATOW: Let me then in the few minutes we have remaining, let’s talk about how we create a new roadmap then. What could be a new roadmap if we’re not going to use the amyloid hypothesis? How do we handle this?

DEREK LOWE: That’s not–

GEORGE PERRY: Uh, Dr. Lowe–

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

DEREK LOWE: It’s not an easy one to answer at all.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I mean, yeah.

DEREK LOWE: I mean from a drug discovery and drug development standpoint, I’m going to be a little contrarian and say right now you might, if you’re a drug company, you might not want to work on Alzheimer’s for a bit. You might want to take that money and plow it into basic research or go off and work in other therapeutic areas where you could have a bigger impact on human health. Right now it is such a tough field that you run a very high risk of spending a lot of money for no return.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let me just jump in and say I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

GEORGE PERRY: That would be an unfortunate situation that we’d have to have a hiatus on trials.

DEREK LOWE: Oh certainly.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if you’re a drug company and you’re not making any money after all this research. I mean, after all, you’re only in this for making money, right?

GEORGE PERRY: I know. I know they’re in the business of making money and helping people. I think that the key thing as the field– we need to be looking at new theories for studying Alzheimer’s disease.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Give me a couple of two or three new theories.

GEORGE PERRY: So well, our own work, we focused on the issue of whether there’s a metabolic element to the disease, whether it deals with mitochondrial problems in others. But one thing that we’re doing together with Jim Truchard, a donor is sponsoring a prize for new ideas in Alzheimer’s disease in which the top prize will be $2 million.

DEREK LOWE: Excellent. There are some ideas out there. And I really am curious to see how they come out. And I think that a lot of funding should go into nonamyloid ideas. It may just be a little bit longer before someone’s willing to commit the time and effort to it on drug discovery. And as a drug discovery chemist myself, we need something to work on. And we need a hypothesis that we can screen and test against.

IRA FLATOW: Give me one of those ideas that you have not mentioned.

DEREK LOWE: Well, there’s one kicking around that amyloid might be a response of the brain to other stress, such as even infectious disease. I don’t think there’s a single infectious cause for Alzheimer’s. But it might be that amyloid is sort of a sideshow to something else. And this needs a lot more work put into it. But it’s at least something different than the classic.

GEORGE PERRY: There are several companies doing trials on this related to periodontal disease.

DEREK LOWE: Yes

GEORGE PERRY: Our own work, when I was mentioning the study of mitochondrial metabolism, we think that the amyloid is a protective response to the disease.

DEREK LOWE: Exactly.

GEORGE PERRY: We suggested this beginning about 20 years ago that amyloid removal will have a detrimental effect for patients because it’s playing an antioxidant role.

DEREK LOWE: It’s true. It may be that amyloid doesn’t give you Alzheimer’s but Alzheimer gives you amyloid.

GEORGE PERRY: Correct. And it follows the disease really well. And it was too simplistic. And why we developed this idea– we’ve initially pursued the amyloid hypothesis. And then as we did further experiments, we found that the amyloid was playing always a protective role and keep neurons alive.

IRA FLATOW: Did doctors get together and just throw out ideas about research, where we should head, and have meetings? I mean, it sounds like it could go anywhere with this.

DEREK LOWE: That’s the good part and the bad part.

GEORGE PERRY: Yes. But you know, there’s been a tremendous amount of orthodoxy pushing the amyloid idea. There was a recent article in Stat talking about the amyloid cabal and dealing with how many negative repercussions there were for people that questioned the amyloid hypothesis.

DEREK LOWE: Yeah. It’s true. I mean drug companies put a lot of money down on these ideas. But in academia, people put their careers down on them too. And it can be very hard to change course.

IRA FLATOW: It’s very hard to come up for a new idea to breakthrough after you’ve worked on something for so long. I can understand that. We come across that all the time when we talk about stuff here. But I want to thank both of you for opening our eyes to different ways of thinking. Dr. George Perry, professor of biology, UT San Antonio and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. Dr. Derek Lowe, drug researcher and author of “In The Pipeline” blog for Science Magazine. Thank you, gentlemen, for taking time to be here today.

DEREK LOWE: No, thank you.

GEORGE PERRY: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And check back with us if you come up with a great idea. OK.

DEREK LOWE: Will do.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.