A Science Hero, Lost and Found

12:12 minutes

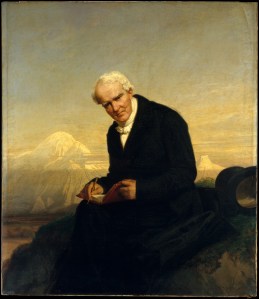

Alexander von Humboldt was a globetrotting explorer, scientist, environmentalist, and the second-most famous man in Europe—after Napoleon. So why haven’t you heard of him? This week we revisit an interview with writer and historian Andrea Wulf, whose 2015 book The Invention of Nature aims to restore Humboldt to his rightful place in science history. Not only did this singular polymath pioneer the idea that nature is an interconnected system, but, Wulf argues, he was also the lost father of environmentalism.

Ira speaks with Wulf about the man who inspired the likes of Darwin, Thoreau, and Muir, whom contemporaries called “the Shakespeare of the Sciences.” Read an excerpt here.

If this book sounds like a great read for your upcoming vacation, you’re in luck! The SciFri Book Club is reading The Invention Of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World by Andrea Wulf in August. Find out all you need to know, including how to win a free book on our website.

Andrea Wulf is the author of The Adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt, The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World, and The Founding Gardeners. She’s based in London, England.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Here’s a trivia question for you. Who has more places named after him than anyone else? Of course, you’re thinking George Washington, right? No, not even our first president can claim a Brazilian river, Mexican mountain, a glacier in Greenland, and an area of the moon, not to mention here, in the States, four counties and 13 towns.

That distinction goes to a globe trekking explorer, scientist, and environmentalist named Alexander von Humboldt, a guy whose notoriety in the 19th century made him the second most famous man in Europe after Napoleon. Well, that was then, now is now. Today, he’s largely forgotten. But my next guest has been working to change that.

Back in 2015, I talked to author and historian Andrea Wulf about her book, The Invention of Nature. In it, she argues that Humboldt did nothing less than change our understanding of nature. It was the overwhelming community choice by members of our SciFri Book club who will be reading it in August. Andrea, welcome back to Science Friday.

ANDREA WULF: Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: If we know the name Humboldt today, it’s probably because of Humboldt Park in Chicago, right? We have Humboldt County in California. What was Humboldt’s reputation in his day?

ANDREA WULF: Well, he was the most famous scientist of his age, which seems mad to us now, because very few people, at least in the English-speaking world, have heard about him. Every schoolchild in the mid-19th century had heard his name. Every scientist who went to Europe, went to Paris, where he lived, or later to Berlin, where he lived, to see him. It was like a rite of passage, basically.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm, not even our most famous scientists today are, as you say, as famous as Humboldt. What did he specialize in?

ANDREA WULF: Well, that’s the thing. He didn’t specialize in anything. He was a genius polymath who really roamed across the disciplines. He was interested in nature as a whole. In fact, he comes up with this concept of nature as an interconnected whole, as nature as a web of life, or we would call it today as an ecosystem, although he didn’t use the term.

So he was looking at plants, for example, not through the narrow lens of classification as other scientists, but looking at them in terms of their vegetation zones, their habitats, the climate. So he looks at Earth as this living organism.

IRA FLATOW: He sort of invented ecology.

ANDREA WULF: Yes, he is very much interested in this– I mean, he sees nature almost like as this tapestry, where he looks at animals within their habitat and plants within their habitat. And then, because he sees nature as a web of life, he also realizes that nature is threatened.

So if you see nature as a tapestry, you basically, when you pull one thread, the whole thing might unravel. So he also becomes the father of environmentalism, really, because he predicts harmful human induced climate change in 1800.

IRA FLATOW: How did he get interested in all of this? Where does he come from?

ANDREA WULF: So what I love about him is that he’s not this kind of cerebral scholar. He is brazenly adventurous. He comes from a very wealthy Prussian family in Berlin. And when his parents die, he basically spends his entire inheritance on a five-year exploration of Latin America. And he ventures deep into the rainforest in Venezuela and across the Andes.

And so he’s kind of physically, incredibly fit. And he sees all these different parts of the world. And he realizes that there are similarities across continents. So he really defines these kind of global vegetation and climate zones, all these things which we take absolutely for granted today, but which were completely new at his time.

IRA FLATOW: In that vein, you describe a pivotal moment to when he climbs up Ecuador’s mountain, considered to be the highest in the world at that point. What was so pivotal about that climb?

ANDREA WULF: So he climbs Chimborazo, which is then believed to be the highest mountain in the world, which is about 100 miles south of Quito in today’s Ecuador. And he climbs up, and he reaches more than 19,000 feet. So no one has ever been that high as he has. And he holds the world record for several decades.

And as he’s standing on top of the world, he looks down, and his vision of nature clarifies because what he realizes is that the journey from Quito up to the peak of Chimborazo was like a botanical journey from the equator to the pole. So he sees the tropical species like banana trees and palm trees in the valley. And then the further up he comes, the plants changes according to altitude.

And he realizes that the plants he’s seeing on Chimborazo are very similar to some of the plants he’s seen before in Europe, say, for example, in the Alps in Switzerland or in the Pyrenees in Spain. So he realizes that there are these corresponding vegetation zones across the globe. So what clarifies at that moment really for him is that nature is a global force. And that’s an extraordinary concept to have at that time.

IRA FLATOW: I’ve got to ask at this point– we’ve talked so much about him– what happened? I mean, why did his name drop off the map so literally, so to speak?

ANDREA WULF: I think there are several reasons for that. One is I think that some of his ideas have become so self-evident, almost. We have absorbed them almost by osmosis that we’ve forgotten the man behind them. So that’s one thing.

And the other thing is that he’s really the last of all polymaths. So he dies in 1859, which is really the last moment where one person can hold all the knowledge of the world in one head, basically, because after that, the sciences specialized so much. So scientists become experts, and they actually look down on people like Humboldt and regard them like amateurs.

And then the third reason, which I think is the most important reason, really, is that he is famous until World War I. And then, neither America nor England is really the right place to celebrate a German scientist. This is a time when the English royal family, for example, changes their surname to Windsor because their other surname sounded too German, where you have public libraries in America burning German books.

So he gets really pushed away. And the interesting thing is that in Latin America, where he traveled for five years, he is famous. He’s as famous as Jefferson and Washington is famous here because he was quite instrumental, through his friendship with Simon Bolivar, in the revolutions in South America.

IRA FLATOW: But he went all over the place, didn’t he?

ANDREA WULF: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: He had a relationship with Charles Darwin.

ANDREA WULF: Yes. Well, Charles Darwin admired Humboldt. And actually, Charles Darwin said that he would have not boarded the Beagle and therefore not conceived The Origin of Species without Humboldt. So Darwin, as a young man, read Humboldt’s books. And that actually made him go to South America.

Once he was in South America, Charles Darwin then said that he could really only see the new world through the lens of Humboldt’s writings. Then later, he modeled his own writings on Humboldt’s books. Like, Voyage of the Beagle is very similar, in that style. And he also used Humboldt’s books as source material, really, while he was working on his evolutionary theory. So he was greatly influenced by Humboldt.

But there’s this wonderful scene where Darwin meets Humboldt finally in 1842. So this is after the Beagle. And this hero of his, which has really grown to mythical dimensions in his head, is this old man who’s so used to being the center of attention and who just talks all the time, and Darwin can’t get a single word in and is really disappointed.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] And he wasn’t just analytical. I mean, he believed, right, in bringing emotion to science, or as scientists today try to be emotionless, he thought that you had to be committed and emotional.

ANDREA WULF: Yeah, so I mean, on the one hand, he’s obsessed with measurements. That’s why he schleps around his instruments through Latin America. But he also says that we have to use our imagination and our emotions to understand nature. So he really bridges enlightenment and romanticism, but he also provides people like Henry David Thoreau, for example, with an answer to how to bring together poetry and science.

And I think I mean, people like John Muir, for example, really follow Humboldt in that you can only protect nature if you really love nature. So these guys are all driven by this sense of wonder and this love of nature.

IRA FLATOW: Right, it sounds like you’re sort of trying to spread the word about Humboldt.

ANDREA WULF: Yes, it’s absolutely a mission. It’s weird. So I’ve written a few books, and this is for the first time that I don’t feel like I’m on a publicity tour for my book. It’s like I’m on a publicity tour for Humboldt. I want everyone to know him because he needs to be restored to his rightful place in the Pantheon of Nature and Science. He’s incredibly important, and he’s shaped the way we think about nature. And everyone should know about him.

IRA FLATOW: How do you do that?

ANDREA WULF: Well, I try to tell a good story about him. I tried to do him justice with this book. Because I’m German, I was able to read a lot of the German original sources. Because he’s really suffered from some very bad English translations of his books because his books are beautiful. And he writes really– his writing is a blueprint of all nature writing today because he combines these evocative landscape descriptions with scientific observations. So, I try my best, but–

IRA FLATOW: Well, is now a good time? Is the time right in society and culture and environmentalism?

ANDREA WULF: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Global warming, all that stuff?

ANDREA WULF: I think that he is incredibly relevant at the moment because, well, one thing is that his story really explains why we understand nature the way we do it. But he’s also– one of his greatest achievements was to make knowledge accessible and popular. He wanted to unite scientists. He wanted to foster communication across disciplines, which these are incredibly important pillars of science today.

And probably, most importantly, today, as scientists are trying to predict and understand the global consequences of climate change, Humboldt’s interdisciplinary methods and his idea that nature is one of global patterns, remains resoundingly topical. And the other thing is that he looked at colonialism and the destruction of the environment as one system. So his insight that economic, social, and political issues are connected to environmental problems, sadly, still incredibly important today.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’re very lucky, Andrea, to have you to write this book for us. It’s a terrific book. I highly recommend it. And thank you for taking the time to be with us, and good luck.

ANDREA WULF: Well, thank you for letting me talk about Humboldt.

IRA FLATOW: Andrea Wulf is the author of The Invention of Nature. I talked to her back in 2015, when her book came out. If this book sounds like a great read for your upcoming vacation, you’re in luck because the SciFri Book Club is reading The Invention of Nature in August. Find out all you need to know, including how to win a free book– oh, yeah– on our website, sciencefriday.com/bookclub.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.