This Alaskan Glacier Is Moving 100 Times Faster Than Usual

02:22 minutes

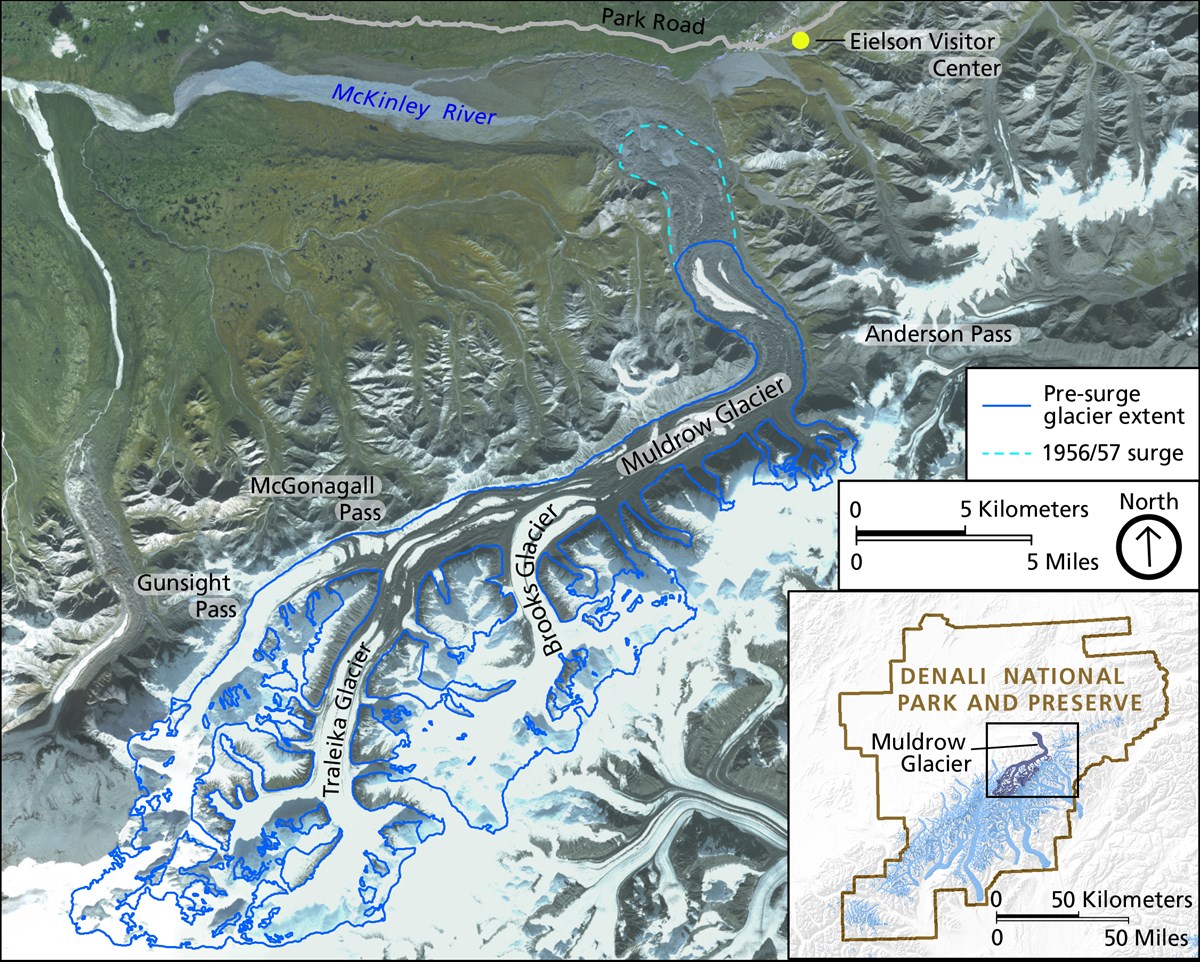

One of the glaciers on Alaska’s Denali mountain has started to “surge.” The Muldrow Glacier is moving 10-100 times faster than usual, which is about three feet per hour. About 1% of glaciers “surge,” which are short periods where glaciers advance quickly.

Geologist Chad Hults has been on the glacier to study it during this surge period. He talks about how the glacier’s geometry and hydrology contribute to this surge period.

You can listen to the haunting sounds the glacier makes as it moves below. This was recorded on the main stem of the glacier. “It was snow covered, so it is very quiet, but there is constant cracking and booming of the glacier,” says Hults. “And a Pika in the background.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Chad Hults is an Alaska regional geologist with the National Park Service in Anchorage, Alaska.

IRA FLATOW: Up in Alaska, one of the glaciers on Denali mountain has started to surge, and I mean really move. The Muldrow Glacier is slip sliding away 10 to 100 times faster than usual, about 3 feet per hour.

CHAD HULTS: You can’t necessarily to see it move, but you can see evidence of it moving.

IRA FLATOW: Chad Hults is the regional geologist for Alaska National Parks.

CHAD HULTS: It’s pushing up dirt mounds. You can hear the sounds of ice crashing almost constantly, so you should be able to see it if you sat there and had lunch.

IRA FLATOW: He flew out with his team and landed a helicopter on top of the cracked surface to study the glacier.

CHAD HULTS: And this glacier, in its normal state, looks very boring. It’s all covered with debris. It’s got a lot of melt ponds and channel flow on top of it. But then, now, it’s just like, woke up the dragon, and the thing is just raging down the mountain.

IRA FLATOW: About 1% of glaciers surge. Here’s what happens. Ice can dam up for long periods of time. The last time Muldrow surged was 64 years ago, so that’s nearly seven decades of ice buildup.

CHAD HULTS: And because you build up basically a hydrologic head in the glacier, it effectively floats the glacier with that water build up. Because you have so much potential energy in the upper reaches of the glacier, it just finally reaches a threshold and releases. All the water starts going to the base. It just basically lubricates the bottom of the glacier, and it just completely free flows until it releases that water in the end of the surge.

IRA FLATOW: Chad and his team use radar satellite data to figure out this surge started back in September. Chad calls this a once-in-a-lifetime, once-in-a-career event. He’s placing seismometers to capture the sounds of Muldrow to study how water is flowing through the glacier. These surges are a natural phenomenon and not due to climate change, says Hults, but because these events are so rare, the role climate change might have is unknown.

And yes, if you are in Alaska, you can view Muldrow on the move from a safe distance. If you can’t make it out there, you can see photos of Muldrow and hear sounds of the glacier from these seismometers all on our website at ScienceFriday.com/glacier.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.