After Finding Thousands Of Exoplanets, Kepler Rides Into The Sunset

9:14 minutes

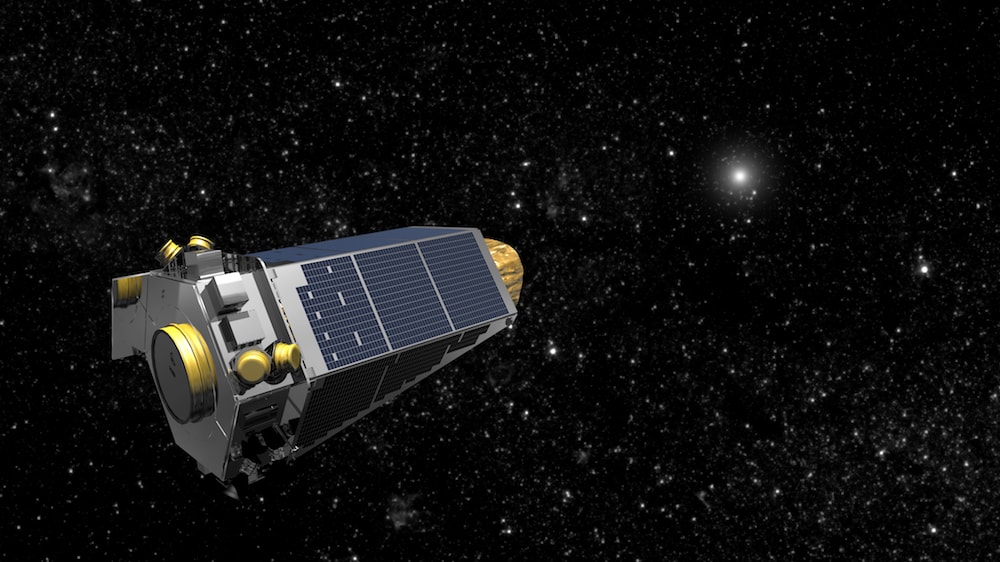

NASA launched the Kepler space telescope in 2009, with plans for it to operate for about three and a half years. However, the instrument has stayed in operation for over nine years, spotting over 2,500 confirmed exoplanets between its initial run and the subsequent modified ‘K2’ mission.

[Yep, this porg-like creature really existed at one point.]

Now, the Kepler telescope is close to running out of fuel. Geert Barentsen, an astrophysicist and the director of the Kepler/K2 guest observer program, joins Ira to look back at the Kepler planet-hunting mission, and talk about TESS, the next-generation planet hunter scheduled for launch next month.

Geert Barentsen is Director of the Kepler/K2 Guest Observer Program at NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California.

IRA FLATOW: NASA launched the Kepler Space Telescope in 2009. And it was supposed to operate for, what, about 3 and 1/2 years. Well, it’s kept running for over nine years and, during that time, has spotted over 2,500 confirmed exoplanets. But now, its end is in sight. I’m sorry to say that. Joining me now is Geert Barentsen, an astrophysicist and director of the Kepler/K2 Guest Observer program at the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California. Welcome to Science Friday.

GEERT BARENTSEN: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: We’re sorry to hear. Why is Kepler coming to an end?

GEERT BARENTSEN: Well, Kepler is now 94 million miles away from Earth. And just like what would happened on the long road trip, our fuel is running low. And of course, there are no gas stations in space. But we’re not actually sad at all because Kepler has been taking so much data. It’s this gold mine of data. And actually, we think it’s going to take another decade to sift through all the data.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so for those of us who may have forgotten, what is Kepler’s mission?

GEERT BARENTSEN: Well, Kepler was NASA’s first exoplanet mission. And what that means is it took the first census of planets outside our own solar system. So Kepler is a telescope. And what it does is it’s like a big bucket of light. And it is looking at stars, measuring their brightness, and what it’s looking for is like minute dips in the brightness of stars because when a planet moves in front of its star, we can record this by looking at the brightness carefully. And when this dip happens periodically, we know that a planet must be orbiting that star.

IRA FLATOW: Quite interesting. A few years ago, I remember parts of the telescope were failing, but you kept it going. How did that happen?

GEERT BARENTSEN: That’s right. So Kepler uses spinning wheels called gyroscopes, which keeps its gaze stable. It needs a really accurate pointing to keep the stars very, very centered on the detectors. Now, two of those wheels failed a few years ago, but our incredible engineers actually came up with this fantastic solution. They were able to point the solar panels of the spacecraft to the sun in such a way that the spacecraft could be maintained stable using the pressure of sunlight, which by the way is an insane idea. But it worked.

IRA FLATOW: Don’t you love it when that works?

GEERT BARENTSEN: NASA has some of the best engineers, and it’s such a privilege to work with them as a scientist.

IRA FLATOW: All right, give us a highlight. Now, you’ve got your Kodachrome slides out on the screen here. Give us a highlight of your most favorite discoveries and the biggest contributions that Kepler has made so far.

GEERT BARENTSEN: Well, the big contribution is really discovering that planets, rocky planets, are common. We found more than 2,600 planets. I know you said 2,500 in the introduction. But actually, it’s now 2,600 just because in the last month, we found another 100.

IRA FLATOW: Oh my goodness.

GEERT BARENTSEN: And it’s an incredibly diverse universe out there. We found hot lava planets. We found cold icy planets. We found rocky Earths, and large super Earths, and fluffy mini Neptunes, and all sorts of crazy things. And perhaps the discoveries I’m most excited about right now are things we’ve just been seeing in the last moment such a supernova explosions.

IRA FLATOW: And you have citizen scientist planet hunters going through the data, helping you out to sift through all that data.

GEERT BARENTSEN: Kepler looked at more than half a million stars now. What many people might not appreciate is that, ultimately, the discoveries from Kepler are made by humans on Earth and not by the spacecraft itself. But it’s so much data that astronomers have been overwhelmed. So one thing we did is we put– All these data is public, and we went one step beyond. We made it easy interfaces and tools for people to sift through the data, and just back in January, we announced a planet system with five planets. And it was actually first discovered by a car mechanic in Australia who doesn’t have a degree in astronomy. But he likes the night sky, and he found this system.

IRA FLATOW: You’ve got to be very patient, I would–

GEERT BARENTSEN: You do have to be patient, but – reward is big because Kepler is really putting our own planets and our species into context.

IRA FLATOW: What’s the closest planet to us that might have some sort of life on it that Kepler may have found?

GEERT BARENTSEN: The closest planet we know today is a planet around the nearest known star, which is Proxima Centauri. Now, Kepler did not find that planet. Kepler did find a planet just in September called Gliese 9827. We like long boring numbers, and that one is just 100 light years away. And the reason that’s interesting is because the Hubble Space Telescope, right now, is looking at this object this year. And the future James Webb Space Telescope will be studying the atmospheres of the planets in that system more carefully in the future.

IRA FLATOW: I think it’s a really interesting how you’re able to get smaller and smaller planets to see them.

GEERT BARENTSEN: Absolutely, and in some sense, Kepler is only like a strategic cog in the real of NASA’s long term objective to answer the big question, which is, are we alone? That’s a question, which is perhaps one of the most fundamental questions our species can ask. And in the coming years, we’re going to see more missions come online which will help us answer that question. In fact, NASA is launching a new mission called TESS next month, which is going to help.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll talk about that right after I tell everybody that this is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, Talking with Geert Barentsen, director of the Kepler/K2 Guest Observer program. All right, let’s talk about TESS. It’s scheduled to be launch, what did you say, next month? What is it? How does it differ from Kepler?

GEERT BARENTSEN: So TESS is an acronym. It stands for the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. And it is going to look for planets in pretty much the same way as Kepler did, except now that we know that planets are ubiquitus– we think there might be trillions in the galaxy– TESS is going to focus on finding the planets that are around the most nearby and brightest stars in the sky. And astronomers love bright stars because we can split the light of bright stars into colors, using advanced instruments called spectrographs. And when we do this, in those colors, we can see the chemical fingerprints of atoms and molecules, which help us understand exactly what these planets and their atmospheres are made of.

IRA FLATOW: How is TESS going to be different from the upcoming Webb Space Telescope?

GEERT BARENTSEN: So TESS is really about finding the planets. TESS is an array of small telescopes. And it will find the planets, which then James Webb and other instruments will follow up.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, how do you go about finding? How do you know where to point? Is there a sweet spot in the sky? How much of the sky can you take in at any one time?

GEERT BARENTSEN: Well, so this is the key difference between Kepler and TESS. Kepler was a statistical mission. It asked, how common are planets? And the answer was very common. But it only looked at a small patch of sky where it could do a large number of stars. Now, TESS, in some sense, is doing the opposite. It will, perhaps, look at less stars, but it will do all the bright nearby stars across the entire sky, which is why its telescopes are smaller. But the planets it finds are more amenable to be studied using James Webb.

IRA FLATOW: It means you’re going to need a lot more people looking at all that sky.

GEERT BARENTSEN: All the data we collect about Kepler and test is public almost straight away. And I’m very proud it’s the case because we need people’s help.

IRA FLATOW: How do you get involved? If I wanted to become part of that as a citizen scientist?

GEERT BARENTSEN: So there are a number of websites people can go to. If you look for Kepler Citizen Science on the internet, you’ll find a few projects called citizen science projects, which often provide an easy interface to look at the data. Now, people who want to go a step beyond can go and look for our software tools and our tutorials. There is one thing I personally work on here at NASA is we make tutorials, which help both scientists and the public work with the data.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so are people getting misty-eyed now that Kepler– I remember when Cassini, a different type of spacecraft, people were really upset, visibly upset. What about Kepler?

GEERT BARENTSEN: We are proud because, as you said, Kepler was designed to operate for about 3 and 1/2, 4 years. We are now 9 years past launch, and this is beyond anyone’s expectations. Also, it is still operating. It is still collecting data. And it is really a goldmine of data, which is going to take a decade to fully to fully sift through. And even though Kepler might retire, all the astronomers on the ground will not. They will be working hard for the next 10 years on the data.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I wish you good luck, and we’ll be following you to, what’s that launch date? What’s the window?

GEERT BARENTSEN: Right now, it is due to launch on April 16, and it is on schedule. For

IRA FLATOW: TESS, T-E-S-S, standing for?

GEERT BARENTSEN: Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, OK. Well, you promise to come back and talk about it a little bit when it’s up there?

GEERT BARENTSEN: That would be a privilege.

IRA FLATOW: And we would love to have you back. We’ve run out of time now. Geert Barentsen is an astrophysicist and director of the Kepler/K2 Guest Observer program at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California. Have a good weekend.

GEERT BARENTSEN: Thank you.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.