A Tiny Martian Colony, Here On Earth

17:39 minutes

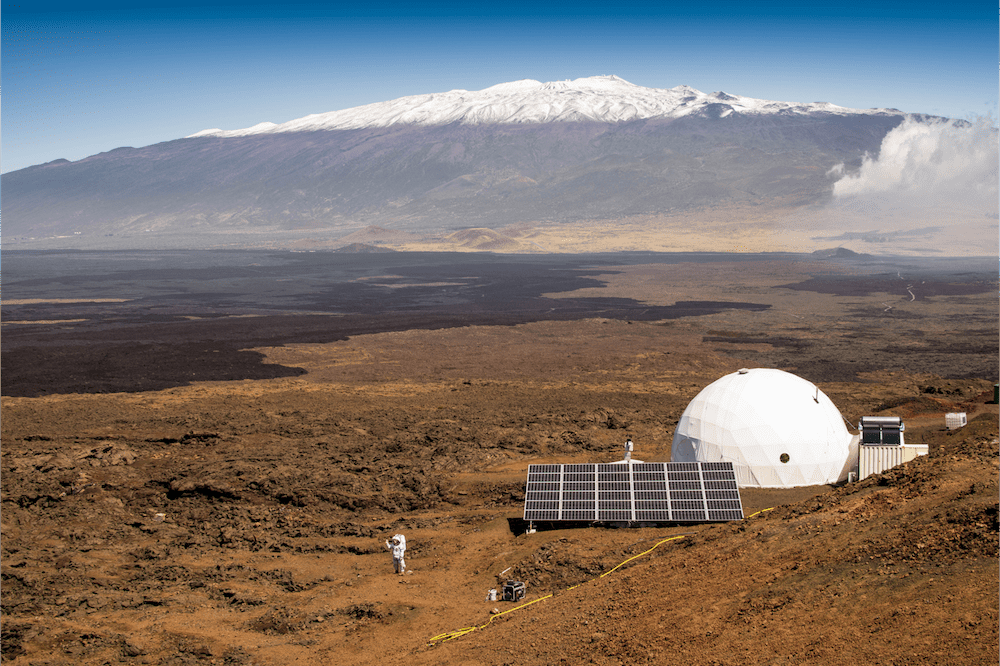

Perched on the side of the Mauna Loa volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island is an otherworldly experiment—a Mars colony where half a dozen crew members spend eight months living together and simulating life on the Red Planet. The location looks altogether unearthly, with rusty red rock fields that look a lot like the images being sent back from the surface of Mars.

[Most people agree a meteorite wiped out the dinosaurs. One scientist isn’t buying it.]

What happens when you jam six people in a 1,200 ft2 habitat for months at a time? Kim Binstead, the principal investigator on the HI-SEAS project and a professor of information and computer sciences at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, joins Ira to give a glimpse of what life is like inside.

Kim Binsted is the principle investigator of the HI-SEAS project. She’s also a professor of information and computer sciences at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, coming to you from the Hawaii Theater Center in Honolulu.

[APPLAUSE]

Now, Hawaii has an incredible diversity of climates and landscapes, rain forests and grasslands, pine forests, beaches. You even have snow here, too, which is really interesting to learn about. But it also has places that look altogether not of this earth. And I’m talking about the rusty red rock fields atop the island’s volcanoes, which look a lot like those pictures the Curiosity Rover was sending back from Mars.

And it’s there on the flanks of Mauna Loa on the big island that scientists are simulating missions to Mars to learn what happens when you jam six people into a 1,200-square-foot habitat for months at a time. My next guest is the principal investigator on that project called HI-SEAS and a professor of information and computer sciences at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Kim Binsted, welcome. Come on.

[APPLAUSE]

Nice to have you here.

KIM BINSTED: Great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Give us a thumbnail print of what the HI-SEAS experiment is. Where is it? what’s going on?

KIM BINSTED: So HI-SEAS stands for Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation. It’s on the side of Mauna Loa at about 8,000 feet. And what we’re trying to do is to simulate a Mars exploration mission– so what the surface part of sending humans to Mars and bringing them back would be.

IRA FLATOW: You’re not planting stuff to eat there like they show in the movie. You’re not putting potatoes out on the ground or anything like that.

KIM BINSTED: You know something? The Martian the movie has made my life so much easier.

IRA FLATOW: Is that right? Why?

KIM BINSTED: It makes it so much easier to explain what I do. People used to be like, why worry about the food? And now all I have to say is, remember when Matt Damon ran out of ketchup?

IRA FLATOW: So what is the idea? What is the main object that you want to know about the people in there?

KIM BINSTED: Yeah, we’re looking at the people. So we’re looking at how to put crews together, how to pick the individuals to form a crew, how their cohesion and their performance changes over these many months of the mission, and basically what we need to do to send them to Mars and bring them back without them killing each other.

IRA FLATOW: And why Mauna Loa? What’s unique about that spot there?

KIM BINSTED: It’s a beautiful spot. It looks very, very much like Mars, both visually and also geologically. It’s quite a bit like Mars. So Mauna Loa is a shield volcano. And the volcanoes on Mars are also shield volcanoes. Mauna Loa has lava tubes. Mars probably has lava tubes. So it is very much like Mars in that way.

IRA FLATOW: Now, do you have to select certain personalities that you think will get along with one another?

KIM BINSTED: We do a whole range of psychological testing. But what it comes down to is what a colleague described as thick skin, a long fuse, and an optimistic outlook.

IRA FLATOW: How hard is it to find people with those?

KIM BINSTED: You know, I would actually add one more to that, which is easily entertained. Because if you really need to go out clubbing or if you need to go surfing on the weekends to be happy, you’re not going to be happy on Mars.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s sort of a Goldilocks sort of thing. You have to find a little bit, not too much– the right mixture.

KIM BINSTED: Exactly, especially the extrovert and introvert balance, because you have to get along with people because you’re going to be in a small space with them for a long time. On the other hand, you’re not going to meet any new people for about three years.

IRA FLATOW: Are they able to communicate with people on the outside world?

KIM BINSTED: They are, but there’s a delay. So depending on where Mars and Earth are, the delay can range anywhere between about five minutes and about 25 minutes for a signal to get from one to the other. We settled on 20 minutes. So when you send an email from HI-SEAS, it takes 20 minutes for it to arrive. So the fastest possible answer you’re going to get is in 40 minutes.

IRA FLATOW: I guess people realize what they’re getting themselves into. Or maybe they don’t realize.

KIM BINSTED: I think people have been surprised at how they’ve reacted to it. Everyone goes in very confident. The people we choose a very astronaut-like in their attitude and their psychology. So I think they are confident that they’re going to do well. And they find it more challenging than they thought it was going to be.

IRA FLATOW: One thing I learned is that they have to give up their internet connection, is that right? Their cell phones and things like that?

KIM BINSTED: All real-time communication is out. You can’t surf the internet because if you click on a link, it would be 40 minutes before anything happened.

IRA FLATOW: Mine’s like that already. I’d fit right in there. You know, it’s interesting, because I spent some time as a journalist in Antarctica where people winter over. And they go through the same sort of isolation. It’s something predictable, and they’ve learned from that experience.

KIM BINSTED: Yeah. We call places like Antarctica “serendipitous analogs.” They’re not intended to be Mars simulation mission-like, but they are in a lot of ways. So are submarines. So even are prisons to some extent.

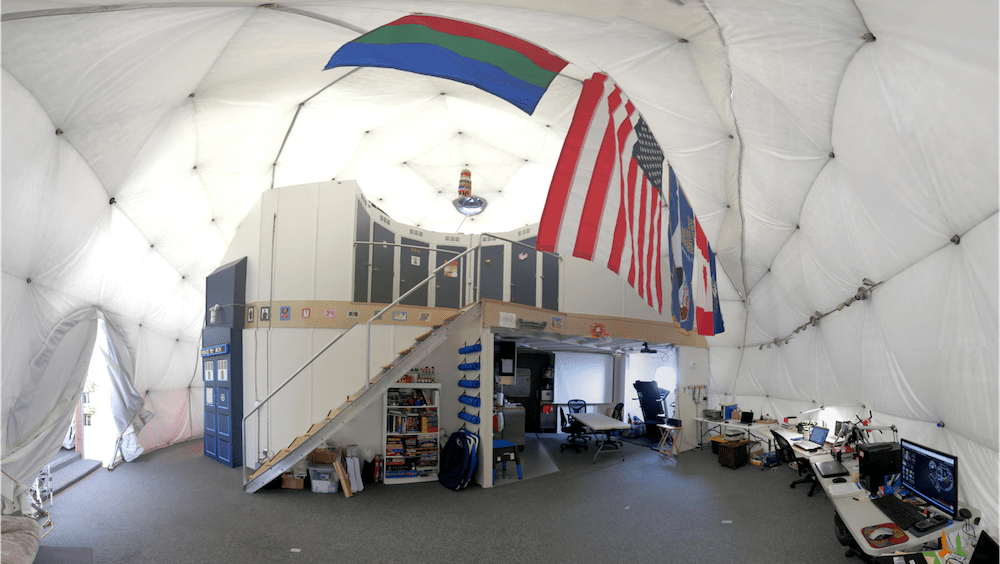

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about what the habitat actually looks like. And we have some illustrations. What are we looking at here?

KIM BINSTED: So it’s a dome. And on the ground floor, there is a large, open area that is reconfigurable. So they used that for their workouts. They use that when they’re doing their work during the day, relaxing at night. There’s a kitchen. There’s a small laboratory. And there’s a bathroom.

Now, the bathroom contains a composting toilet– quite a fancy composting toilet, but still. And there’s a shower. They’re allowed eight minutes of shower time per person per week. Have to say, our crew tend to be very type-one personalities, so they push that as far as they can. One of our crews got that down to four minutes per person per week. And one person on one crew did not shower the entire time.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll bet you that person wasn’t asked back again, too.

KIM BINSTED: Actually, their crewmates said it was just fine. He kept himself– and it was a he, obviously.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Obviously.

KIM BINSTED: They kept themselves clean. They just didn’t do it with a shower.

IRA FLATOW: You know, I remember when I lived with my roommates in college. You know what the worst part was? The dirty dishes in the sink. Who was going to clean those up, right? Did they have those kinds of–

KIM BINSTED: Yeah. We call them– you get sensitive to microstimuli. And that’s just a fancy way of saying you suddenly can’t stand the way your crewmate chooses cereal or whatever it happens to be. Suddenly it goes from, oh, that’s a bit irritating, to murderous levels.

IRA FLATOW: Yes. I’ve been there. We have some microphones in the audience on the sides, so this side and outside, if you’d like to ask questions. So let me see if I have– oh, we have a question right here already. Go ahead.

AUDIENCE: I’d like to know, how do you prepare them for their return journey?

KIM BINSTED: Well, it’s interesting. So our return journey is not very realistic. Basically, I just show up there in a UH van. But I do make it a bit of an event. I ask them what they want to eat. And after 4 months, 8 months, 12 months in the habitat, that becomes a very important question.

So then I spend a couple of days prior to them getting out assembling the raspberries or the McDonald’s hash browns or whatever it happens to be. We save the beer for later. So we have a breakfast when they come out.

In terms of preparing them, they’re very eager to get out. And one thing that seems to happen every time that surprises them, at least, is they can only go outside in their spacesuits. So they’ve been looking at the world through a plastic visor for months.

And they get out, and they say it’s like going from a little black and white TV to a high def television in one move. They’re like, can you see the details in this rock? Oh my God, the sky doesn’t have scratches all over it. And so that can be pretty exciting.

And then the other thing that happens is everyone gets sick because they’ve been effectively isolated from the mutating viruses and so on of the world for months on end. So the instant they’re in a crowd, they get it.

IRA FLATOW: Question over here, yes.

AUDIENCE: So I’m curious about conflict. Obviously that’s big thing. You brought that up. And with a small crew of 8 to 10 people, if it gets to the point of something like physical assault or what you brought up, murder, what could you do with this person? How do you lock them away? Or how do you keep the crew safe from them?

KIM BINSTED: Well, the ISS plan features duct tape and tranquilizers.

AUDIENCE: That works.

KIM BINSTED: In our case, this is a study with human participants. So we are ethically, of course, obliged to remove them before it gets that far. And we do. So we would remove people if they injured themselves or if we saw signs they were about to injure someone else.

Our goal at HI-SEAS is to figure out how to prevent that. There are other scientists at NASA coming up for a plan for the worst possible case. But in any system of systems– and a Mars mission would be that– if the human element goes badly, it’s just as bad as if the rocket blows up.

IRA FLATOW: Did you ever have to abort any missions because somebody was injured, you had to get them out?

KIM BINSTED: Yeah. In the most recent mission, there was an accident at the habitat. And we had to take them to the hospital. Everyone was fine. But under our protocol, they had to go and be checked out.

IRA FLATOW: Do you ever have any romances that occur onboard?

KIM BINSTED: I’m obliged to protect crew confidentiality. But I guess all I can say is that on one mission– well, actually, on all of the missions– six people go in, and six people come out. And I’m never quite sure whether I’m worried about five coming out or seven coming out.

IRA FLATOW: How long is the mission? And the food that you give them– is it typical astronaut food? Or can they get wine and things like that?

KIM BINSTED: No wine, no alcohol.

IRA FLATOW: No wine, no alcohol? And you still get volunteers?

KIM BINSTED: I know, yeah. We give them shelf-stable food. None of it can require refrigeration, so a lot of it’s dried, freeze dried, and so on. A lot of it I get at Costco.

I wish I could say I was getting it somewhere more glamorous. A lot of it I get online. And I’ll tell you, if you shop for large amounts of shelf-stable food, you get on some really interesting mailing lists.

IRA FLATOW: Better you than me. Over here, yes.

AUDIENCE: Hi. So I have three brothers. And a lot of times, I just need to cool off or something. So I go to my room. Is there any way that people that are in the simulation have a way to cool down or go somewhere else?

KIM BINSTED: So do we tell people to go to their room?

IRA FLATOW: Is there place for privacy in there?

KIM BINSTED: They do have very, very small bedrooms the size of this table and a couple of chairs, really. I don’t think anyone’s ever been told to go their room. But people certainly do go to chill out in their room and to get away from their crewmates every now and then.

And I actually did one of these missions up in the Canadian arctic a few years back. And one day, I just woke up on the wrong side of the bed, as it were. And I realized that when you can’t really get sick– because we’d already run out of all the bugs we’d brought in with us– you can’t have a sick day. And sometimes a sick day is what you need. So we decided that we could take sick days if we wanted. I went back to bed, and that was that day.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. Do you find yourself like a camp counselor? You have to provide the entertainment sometimes for them so they don’t get bored and find fun things for them to do?

KIM BINSTED: We certainly do our best to give them anything that falls within the mission rules. So we record things for them. We send them movies. We send them TV. We send them news, sports. One thing that was quite interesting is they have a 3D printer.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, they do?

KIM BINSTED: Yeah. And so their friends and family couldn’t send them actual things, really. But you could send them a design to print from the 3D printer. And that was quite a fun way to stay in touch.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, here in Honolulu talking with Kim Binsted, principal investigator of the HI-SEAS mission. Let’s see if we have any more questions. Yes, go ahead.

AUDIENCE: Are you prepared for everything?

[LAUGHTER]

KIM BINSTED: No.

IRA FLATOW: You want to sit here in my chair? That was a great question.

KIM BINSTED: No. No we’re not, no. What we’re trying to do is to at least try to understand what we need to be prepared for. So the way that NASA organizes this is they’ve got a bunch of risks.

And for each mission profile, a risk is either green, which means it’s fine, yellow, which means it’s not fine, but it’s acceptable. And red means we’re not going to fly this mission while we still have red risks. So the goal of research like mine is to move these risks out of the red column and into the yellow and green.

IRA FLATOW: Is there something you’d like to add to the mission now that you have experience with it, modify it? Give us an idea about that.

KIM BINSTED: Lots of things we’d like to do. We’d really like to have more realistic life support systems. So we’d like to have a greenhouse, for example. We’d like to have more water recycling. We’d like to have those kinds of systems and start testing those in this kind of scenario because, of course, those will be vital for a real mission.

IRA FLATOW: It was interesting. You touched on it before, but I want to learn a little bit more about the old idea of what the right stuff was in the early days versus now what the right stuff is for an astronaut or someone who’s going to be going on a long mission.

KIM BINSTED: Yeah. NASA used to have this idea– the right stuff idea– that there was sort of an ideal of an astronaut. And then they would pick people who were as close as possible to that ideal.

But I think what we’re seeing on these longer missions– a better metaphor is a toolbox, right? You wouldn’t put six hammers in a toolbox even if they were the very best hammers in the universe, right? So instead, you want to have a range of skills– not just job skills, but psychological skills, backgrounds, communication approaches, and so on– so that no matter what comes up, this group of people can be resilient and can respond to pretty much any problem.

IRA FLATOW: Do you look for people with certain job skills, either they’re handy people or geeky people who could fix something that goes bad?

KIM BINSTED: Yeah. We look for scientists, both lab scientists and field scientists. We need engineers who are both systems engineers and MacGyver types who can fix everything with a piece of duct tape. And we also need people with medical backgrounds. So yeah, a whole range of skills is what we need.

IRA FLATOW: There you have it. Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today.

[APPLAUSE]

Kim Binsted, principal investigator on the HI-SEAS project, professor of information and computer sciences at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Now I’d like to welcome back our musical guest, Makana. Give him a round of applause. Come on out again.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

That’s about all the time we have. Our heartfelt thanks to Hawaii Public Radio for hosting us and to José Fajardo, Bill Dorman, Phyllis Look, Jason Taglianetti, and everyone else at the station for making us feel so welcome. Thank you all.

[APPLAUSE]

Also, thanks to Leese Katsnelson and Dan Johnson. And thanks to all our Science Friday staff. It takes a lot of people behind the scenes to run this ship. And a big thank you to all the great folks at the Hawaii Theater Center and the Kahilu Theater. And most of all, thanks to all of you– all of you out there, our fans. You really have been a great crowd this evening. Thank you all for showing up.

[APPLAUSE]

Couldn’t do it without you. Let’s give a last round of applause for Makana, who’s going to play us out tonight.

[APPLAUSE]

Thank you all for coming. In Honolulu, I’m Ira Flatow. Drive home safely. Have a good night.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.