A Street-Level View Of Neighborhood Change

11:35 minutes

Gentrification happens when a previously low-income or working class neighborhood sees an influx of well-off new residents. Rents go up, new development sets in, and the neighborhood’s original residents may be displaced by those with more money. Cities who can recognize gentrification in progress can take steps to prevent displacement and funnel resources, or even slow the neighborhood’s changes directly. But while a new yoga studio or fancy coffee shop may be one obvious sign of rising rents, there are earlier indications that might help cities fend off some of the side effects sooner—building improvements like new siding, landscaping, and more go markedly up as new money arrives.

Writing in the journal PLOS One this week, a research team at the University of Ottawa describes one new tool in the toolkit: they turned to Google’s Street View, and taught an AI system to recognize when an individual house had been upgraded. Putting those upgrades on a map revealed not just areas the researchers already knew were gentrifying, but also other pockets where the process had begun unnoticed. Michael Sawada, a professor of geography, environment, and geomatics at the University of Ottawa, explains the big data approach to catching gentrification in action.

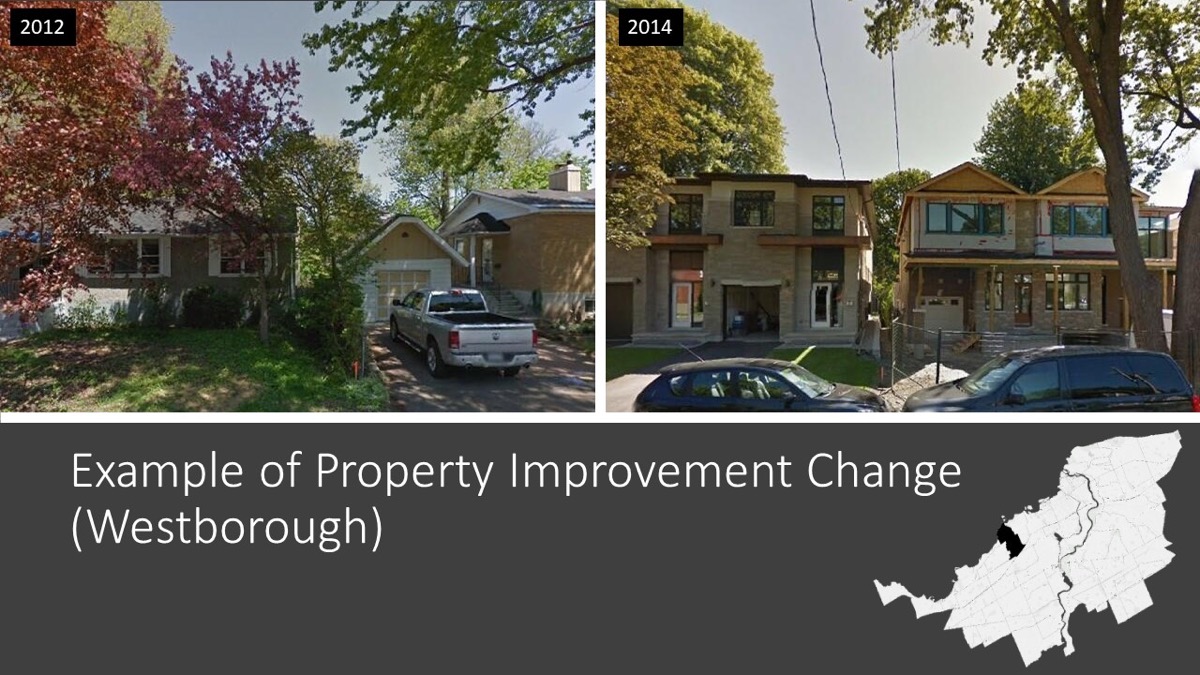

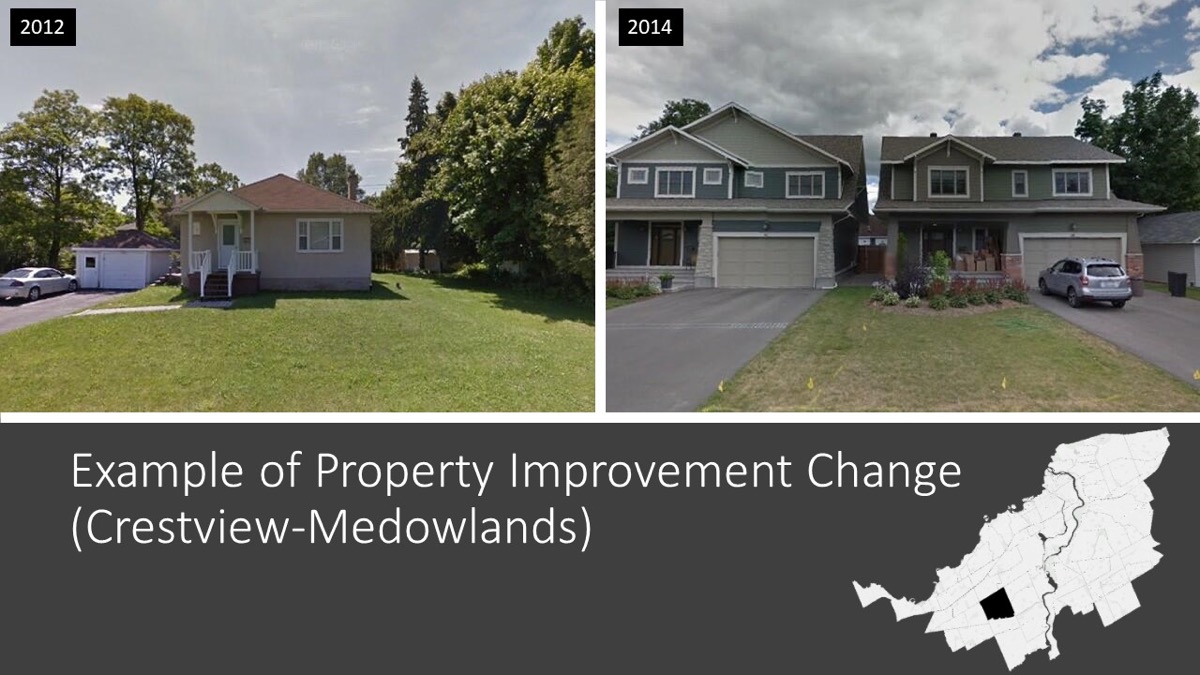

Check out some images from Google Street View of changes in a neighborhood.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Michael Sawada is a professor of Geography, Environment, and Geomatics at the University of Ottawa in Ottawa, Canada.

IRA FLATOW: How do you know if your neighborhood is gentrifying? Well, the rents are skyrocketing, businesses are closing, and a fancy coffee shop is moving in, and a new high rise goes up. Gentrification can be bad news for neighborhoods’ original inhabitants. It can mean they are forced to move or suffer greater economic hardship. But if caught in time, cities can try to soften the negative consequences or make choices that slow the gentrification process.

So how do you catch gentrification in action? How about Google Street View? Researchers at the University of Ottawa tested that big data approach. And here to explain it, Dr. Michael Sawada, Professor of Geography and Environment and Geometrics at the University of Ottawa. Welcome to Science Friday.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: So gentrification is a word that evokes a lot of different things for different people. So do you have a scientific definition of what it is?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Yes, in fact, it’s quite simple. The idea of gentrification pretty much is defined as the– when a more affluent user group or a more affluent group of people move into a less affluent area of the city and displace the residents that are there, simply because the rents become higher and the property prices become higher.

IRA FLATOW: And what is the usual way to measure it?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Well, a measurement is a very important– as you know in science– we need to be able to measure things in order to have a common frame of reference to talk about or define various processes. Gentrification is one of those things that’s been measured in more anecdotal ways in the past. So anecdotally, through interviewing people about their motivations for the gentrification of a particular region or whether they like it or dislike it.

And in the end, it’s come down to using census data, largely. And of course, by the time you can detect gentrification with census data, it’s often over. Because censuses are only taken every five to 10 years in North America, for example. And you–

IRA FLATOW: So it’s not really good–

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: –can miss the process entirely.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it’s got a lot of holes in it, is what you’re saying.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: And your team thought that if we could literally see it in action. And you could measure it better, and you used Google Street View Data.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Sure, well we thought, what we’re looking at gentrification as a process, largely involves the updating, usually, of people’s properties. It’s one of the ways more affluent people express their wealth, for example, is through material means. And that’s where they live. So they’ll update the facades of their properties, a siding, maybe even tear down an old house and put in a new one.

And we can see that now with Street View. We’ve had this intersection of technology in the past couple of years, whereby we have about 10 or 11 years of street view imagery archived by Google. And anybody can go through that and look at them. And at the same time, we’ve had mega advances in deep learning– the ability to go through these large numbers of images with artificial intelligence.

IRA FLATOW: Right, right. And so when you went through known places and compared them to what you were discovering with the Google Street View and the AI, how accurate did that turn out to be?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: It was remarkably accurate. So firstly, we found that our model detected the gentrification that we knew anecdotally was taking place in two of the major regions of Ottawa. One region is an area which is very popular with the hipster culture. And down the street from that is another area. And these two neighborhoods have been undergoing gentrification in the past 10 years.

And we were able to see that right away in our model. These were the hottest of the hot spots of gentrification. So it confirmed that our model was working in detecting what we thought it should.

IRA FLATOW: And were you able to find places where gentrification was sort of hiding out? That no one had seen before?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Yeah, and I think that’s the real advantage of the approach that we’ve put together. Is that by looking at everything, every single building’s Street View sequence of images over time in a large city, we were able to find pockets of gentrification that nobody was really talking about, anecdotally or otherwise.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting, so how do you make use of this new tool in this new data that you have?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: So one of the things that we’re able to do, is that we can now have detailed maps– at least of our city where we’ve done this and shown that it works. So far, we have detailed maps of gentrification happening, where it’s happened, where it’s happening, and how intense that process is. So we’re now able to measure it right down to the property scale.

And this is very important for a lot of different reasons. Foremost being of course, it provides city administrators, managers, the zoning office, the permit office, with critical information about where there’s been large dynamic urban change taking place. But also where it’s starting. So they can then decide, well, should we let this go uncontrolled in a capitalist type of way? Or should we step in and try and mitigate the process, so that we ensure there’s equitable housing and things like that?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, so can other people make use of the Google Street View for other purposes?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Oh definitely, and that’s something we’re doing right now. We’re using Street View to map out two major things in Ottawa. Just as a proof of concept again, one is walkability, and that’s again a very– something you like or dislike. Where you want to walk. You look at a couple of pictures, and we asked people, do you want to walk on the left picture or the right picture? Which one would you rather walk on?

And we can train, then, a machine to go through a Street View and say, well, these are the most walkable areas.

IRA FLATOW: And you could discover what are unfriendly to people. It could be either senior citizens or people with abilities challenges to get around?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Definitely. We’ve just put in a grant proposal– hopefully it’ll be funded– to look at the age friendliness of our entire city using AI and Google Street View again. So using these same big data deep learning techniques can open up a lot of opportunities to target inequalities.

IRA FLATOW: How easy is it for you– can you go to Google and say, hey, I want to use your Street View for urban planning research. Going to give me this stuff? Does it work that easily?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Well, there was a– before July 18th of 2018, it was much easier. Google just gave away Street View, 25,000 images a day for free. Then on July 18th, overnight, they increased their price for Street View by 3000%. And so now, we get 25,000 free images per month, instead of per day. And otherwise, it’s about $7 per 1,000 images after that.

So this type of work is going to be a little bit more difficult for researchers like me or non-profits or even the city governments that don’t have the means to pay the exorbitant cost of Street View now.

IRA FLATOW: Give me an idea, what is an exorbitant cost?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: OK, so let’s say for a city the size of Ottawa, to get the Street View image archive would cost probably about $21,000 or so. Which is a lot of money for a researcher, at least in Canada. Where we don’t have quite the same funding structure as in the US institutions.

So that’s exorbitant for us. And that means that there’s kind of an advantage given to developers, real estate developers, or other types of real estate interests in being able to pay for the information, run models like ours– because ours is open and free– and get that information for themselves to get a competitive advantage before even the city knows or most people know that gentrification is happening.

IRA FLATOW: Or if you wanted to push back. Let’s say if Amazon wants to move into your neighborhood and you need some data about the neighborhood, you’d have to spend on your own money to push back on that.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Well that’s just it. And you know, there are these things called carbon gentrification that’s happening now. Particularly in areas of the US, where you have big centers like Amazon in downtowns. Where of course, the people who work there want to bike to work or walk to work. And so they’re tending to then buy up real estate and what not in regions that are close to their Amazon headquarters, or Google, or whatever it might be.

And therefore people that used to live there can no longer afford to reside.

IRA FLATOW: So gentrification, do you say in general that gentrification is a bad thing? Or that it’s a mixed bag of things?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Well, it’s one thing that everybody has an opinion on.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: And opinions are valid about gentrification. There are advantages to it in terms of urban renewal, particularly when it’s happening in, let’s say a place that’s known for high crime or drugs, that’s run down with a lot of abandoned houses. Well gentrification is great, because it’s going to improve the safety, the visual quality of that neighborhood.

But in some cases, it’s not so good. Such as when you have carbon– Let’s say carbon– it’s people trying to reduce their carbon footprint and buying up homes in established neighborhoods or even climate gentrification, where people are on higher ground in Florida.

Higher ground areas are being bought up by more affluent people. And that then makes more vulnerable populations to everybody else.

IRA FLATOW: You know, if you sit down and you think about this, there’s probably whole bunches of uses as you could make with this data that you haven’t even thought about yet.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Well that’s the exciting thing about it. We’re just at the cusp now of deep learning, big data, and what we can mine from visual imagery like Street View.

IRA FLATOW: So this is kind of exciting big data for urban planners.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Definitely.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, yes and I imagine it’s a growing field. This is something, if you’re studying to be an urban planner, you’d want to know more about it.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Yeah, I would certainly think so. Because it’s the future as the tools, these deep learning tools, these artificial neural networks become more commonplace. And in a couple of years, you won’t have to be able to even program to use them.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: You’ll be able to go online and ask your question put in your Street View Data, and get pictures back. And that’s one of the things that will be happening for putting it in the hands of everybody, quickly. Of urban planners and what not.

IRA FLATOW: What about Google’s competitors? Apple’s View or whatever?

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Well, I don’t know that Apple has a view. Microsoft tried one, Microsoft StreetSide. Tried to compete with Google Street View. It lasted very– for a few years, but now it’s just relegated to some major US cities, and it’s no longer a global effort the way Google has undertaken it, to create that data set.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much, Dr. Sawada, for taking time to be with us today.

DR. MICHAEL SAWADA: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Michael Sawada, a Professor of Geography and Environment and Geometrics, just a little north of us at the University of Ottawa.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.