A New Planet-Hunter Takes To The Sky

7:29 minutes

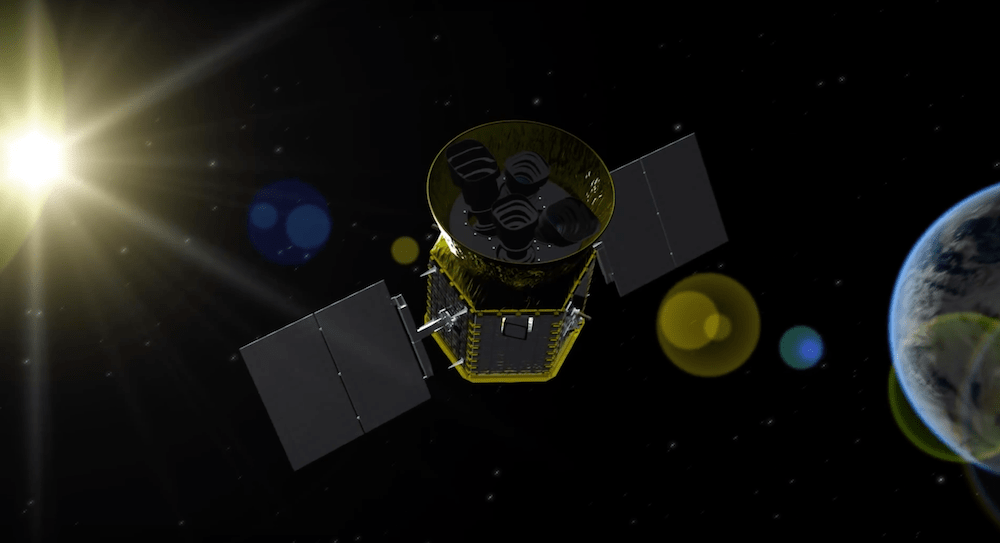

NASA’s Kepler planet-spotting space telescope is close to the end of its life. The instrument is expected to run out of maneuvering fuel in the coming weeks. Fear not, though, planet fans—because a new telescope, named TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), is slated to launch next week.

[Meet the people behind NASA’s Cassini mission.]

Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer at Gizmodo, gives a look ahead to the launch and some other stories from the week in science, including an experiment hunting for a lighter type of proposed dark matter particle called the axion, the discovery of an enormous new species of ichthyosaur, and efforts to use the rules of quantum physics to create truly random random numbers.

Ryan Mandelbaum is a science writer and birder based in Brooklyn, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, we’ll be talking aliens and whether we should be trying to talk to them. Is there a risk there? But first, NASA’s Kepler planet hunting space telescope is failing. But fear not, a new planet finder called TESS is on the way. And here to talk about that and other selected subjects in science is Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer at Gizmodo in our New York studios. Welcome back, on this Friday the 13th. [INAUDIBLE]

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. I actually have a selection of I think maybe some Friday the 13th spooky unlucky stories.

IRA FLATOW: Hit us with number one.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Sure. So Monday NASA’s going to be launching the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, which should be surveying as many as, or perhaps as little as 200,000 stars within the closest 300 light years around Earth, and they’re hoping to find some exoplanets, maybe some Earth 2.0 candidates.

IRA FLATOW: And who’s launching this? Is this one of the SpaceX?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yes, it’s going to be on the SpaceX Falcon 9.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so there’s a lot literally riding on that.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Well, literally, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Literally. So how is this different from Kepler?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Sure. What’s really important about TESS is that it’s looking at the closest stars around us, and these are going to be potential– You know, they’re going to survey it first, and then these will be potential targets for the James Webb Space Telescope, or some successor to the Hubble, to really understand what’s going on around these planets and perhaps having an Earth 2.0 somewhere.

IRA FLATOW: So some of the telescopes, they have a very narrow focus on them, on which part of the universe. This is going to be a wide ranging search?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It’s a survey.

IRA FLATOW: It’s a survey.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Get as much as they can to understand what’s there and then dig into what looks most promising.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Let’s talk about other mysteries of the universe. You have a story about a new dark matter experiment.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: I do.

IRA FLATOW: You love these things.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: I love dark matter.

IRA FLATOW: And I can tell.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Dark matter felt like the perfect thing to talk about today. But I think dark matter fans will remember the WIMP particle as the biggest candidate. But some scientists are getting excited about another potential dark matter candidate called the Axion, which is much lighter than the WIMP, and they’ve gotten experiment in the University of Washington that’s hunting for it.

IRA FLATOW: WIMP is weakly–

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Weakly interacting massive particle. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: And what does Axion stand for?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Axion’s named after laundry detergent actually.

IRA FLATOW: I know that. It’s like a tablet you used to put in. Way before you were born.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Sorry, I’m not old enough.

IRA FLATOW: So how are these different again? How would Axions be different than WIMPs?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Sure, so at Axions would be lighter and their motivations come from different places in physics. Axions specifically solve a problem called the strong CP problem, which we won’t get into.

IRA FLATOW: Good, good.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: There is motivation in particle physics, and ultimately they’re looking to find it with– It would have like a radio signature. They might be able to see with a radio antenna actually. They have to just tune it up.

IRA FLATOW: So why haven’t we seen these in these particles smashers? Why does it show up?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: They’re just way too light, and they interact really weakly with the atoms and with the particles.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re two smaller [INAUDIBLE].

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Too little.

IRA FLATOW: Too little. And if you find them, so what would that tell us about all the theory that’s going on?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: I mean, the thing about dark matter is that it’s something like, you know, matter makes up four percent of the mass energy of the universe, and dark matter makes up a quarter of the mass energy universe. So there’s all this stuff in the universe, and we don’t know what it is.

IRA FLATOW: Not to mention the dark energy.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Don’t even get me started on dark energy, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Is that mind boggling that we don’t know what 96% of our universe is made out of?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Makes my brain leak out of my ears every day.

IRA FLATOW: That’s more than making you hair hurt, I think. All right, let’s move on to this. There’s a new ichythyosaur. So what is an ichythyosaur?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It’s a really big underwater creature. This one, scientists– Well, a fossil hunter in the UK found this enormous jaw bone fossil, and this fossil is, if they extrapolate its size, then they’ve essentially got this maybe 85-foot long giant underwater lizard. And this would be certainly one of the large ichythyosaurs, and only a little bit short of the blue whale, which could be about 100 feet.

IRA FLATOW: So we don’t know much about this, because we just have the one fossil.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s one thing that people do think a lot with these discoveries is OK, all you’ve got is a jaw bone. Now if it’s a different species, how do we know that it scales like this? But it’s sort of a simple basic scaling function that would get you this big lizard.

IRA FLATOW: We know just how big it is, but nothing else about it. You have a story also about something random, more random than your usual stories, which are quite random.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Definitely more random. This is another one of those big physics experiments, but you know cryptography needs random numbers in order to encode things and secure your data. But there’s a lot of concern about the ways they generate randomness aren’t really random.

IRA FLATOW: They’re not random.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Not random enough.

IRA FLATOW: Isn’t random random? But they’re really isn’t random. Random is not really random.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Real randomness. So one way that you can create randomness is by observing a particle. In using quantum mechanics, if you put it in a system where it has one of two possible states, then potentially you can continue to measure that state over and over again to get basically a random coin flip.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: But there’s a problem with that, and this is going to be a little mind boggling. But if you could travel faster than the speed of light, then you’d potentially be able to predict what that particle is going to do. So what they do is they send two particles connected through entanglement, you know, [? speaking ?] actually at a distance.

IRA FLATOW: That’s my favorite subject.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: And then they confirm it the number is actually random based on whether or not the particles were entangled.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, my head did that too.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Same.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Do they actually have a device that generates these?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Oh yeah.

IRA FLATOW: What does that look like?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It’s huge. you have two almost 200-meter long arms of this giant L-shaped thing, and each of them has their own lab and they send a pair of, well, two beams of light particles, split by crystals, down either tunnel, and then they measure them and make sure that things are random. It takes 55 million photons to end up with 10 minutes worth of randomness, which is 1,024 bits of randomness.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll stick with my dice.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Finally, there’s another reason why you might not want it to be the world’s hottest pepper, right?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Oh, yeah. This is perhaps the unluckiest of them all. A man was in a hot pepper eating contest. He tried to eat a Carolina Reaper pepper, and what followed was thunderclap headaches that got so bad he had to go to the emergency room.

IRA FLATOW: Don’t you hate it when that happens?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: All the time.

IRA FLATOW: So he just wanted to eat this pepper, or you know, was it a dare?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It was a contest.

IRA FLATOW: Oh a contest.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah. There’s a chemical in the hot pepper called capsaicin, which is known to interact with other blood vessels. Shout out to my dad, who actually worked with capsaicin back in the 70s or 80s. But anyway, it could constrict or dilate the blood vessels and potentially cause these headaches.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so let that be a lesson to everybody.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Don’t eat too many hot peppers, especially not these.

IRA FLATOW: Bringing on the Friday the 13th. Thank you, Ryan.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer at Gizmodo.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.