The Effort To Save Thousands Of Donor Kidneys From Being Wasted

6:02 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Elizabeth Gabriel, was originally published by WFYI.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Elizabeth Gabriel, was originally published by WFYI.

Sylvia Miles was diagnosed with lupus in 2006, a chronic autoimmune disease that causes the body’s immune system to attack healthy tissue—including her kidneys.

Miles, who lives in Indianapolis, was later diagnosed with advanced kidney disease, and was in need of a kidney transplant.

Kidney diseases are one of the leading causes of death in the United States with 37 million people living with chronic kidney disease. Together with advanced kidney disease—the later stage of CKD—it cost Medicare billions of dollars in recent years.

People like Miles, who need a kidney transplant, wait an average of five years—often on dialysis.

But despite the long waitlists and organ shortages, around 9,000 kidneys from deceased donors last year were discarded due to perceived issues with their viability. A new Indiana-based organization, 34 Lives, is working to limit that waste and rehabilitate the organs.

More than 100,000 patients are on the national kidney transplant list and around 30 people are taken off the lists everyday because they either became too sick for a transplant, or died.

Miles was living in fear and uncertainty.

“The waiting period of just knowing whether or not I was going to get a transplant—if I was going to die before I was able to get a transplant,” Miles said, “was very nerve-wracking.”

Her life finally changed when she received one of the kidneys salvaged by 34 Lives.

Kidney donations come from two sources: living donors and deceased donors.

A living donor kidney is the best option for patients with kidney disease because the organs are typically better matches, healthier and last longer than a deceased donor kidney. But most patients get a kidney donation from a deceased donor through a waitlist system.

The deceased donor kidney is removed from the body, put on ice inside a styrofoam cooler, then an organ procurement organization transports it to a hospital where it’s needed.

That’s when a clock starts ticking. The longer the organ is outside the body, the higher the chances things can go wrong with it.

Transplant surgeons can get a small biopsy of the organ, imaging and some medical information from the donor. But that’s not always enough information, said Dr. Leonardo Riella, a transplant nephrologist with Massachusetts General Hospital.

“These biopsies are processed very quickly, meaning we cannot do all the stains to look at all the different aspects of the kidney,” Riella said. “We may not be able to actually say what’s going on with the rest of the kidney because sometimes things can be spotty in terms of how they affect the kidney.”

The limited information, combined with the short timeframe an organ can stay outside the body, makes it harder for surgeons to be certain the kidney would work efficiently, or at all, once transplanted. This leads surgeons to decline kidneys — some of which may have been healthy enough to use.

Hospitals don’t have the funds or resources to repair damaged organs. Since the Food and Drug Administration hasn’t approved a process for repairing kidneys, a hospital would have to conduct a research study, which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

So, if a kidney can’t be transplanted, it’s discarded.

34 Lives—named after the number of people who are removed from the transplant waitlist every day due to the progression of disease or death—is a public benefit company that is running an observational study, which uses a life support machine to try to preserve kidneys that would otherwise be discarded. The company is housed at Purdue University’s Research Park in West Lafayette, Ind.

“Every kidney transplanted into a patient saves Medicare about $2.5 million,” said Chris Jaynes, co-CEO of 34 Lives.

He said they saved the government over $160 million in the first 10 months of operation.

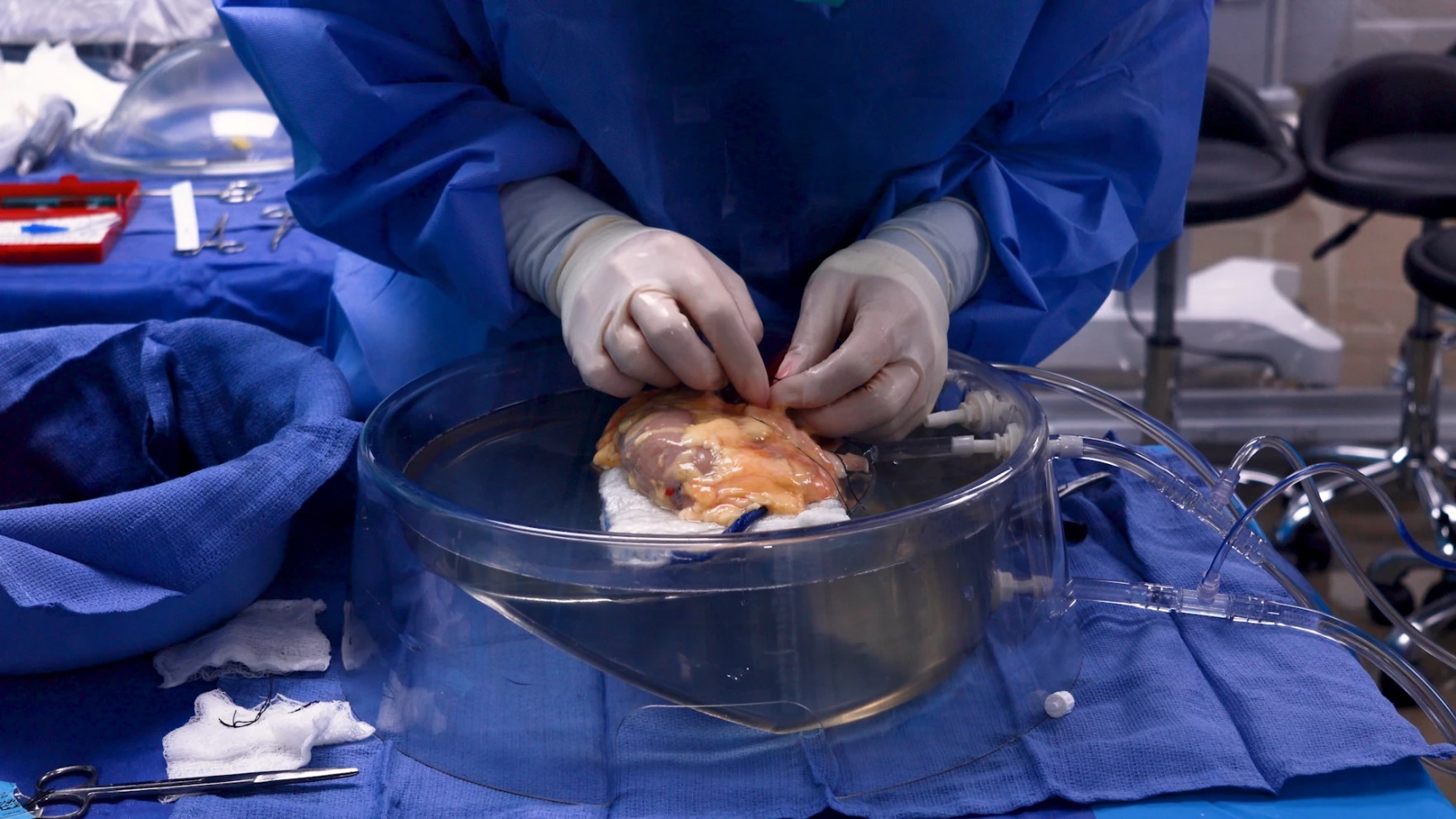

“We put [the kidney] on a little life support machine that allows us to warm it back up to body temperature,” Jaynes said. “And the reason why we do that is because as it’s warm, we almost trick it into thinking it’s still inside a body, and it can start working and functioning just like it was inside a body still.”

The life support machine allows 34 Lives’ staff to run nearly three dozen tests to determine how much sodium, potassium and urine a kidney is producing, and provide a kidney with nutrients, like sugar, so it’s able to heal itself.

A typical kidney can stay outside the body for just 24 to 36 hours. But the observational study team has added nearly 20 extra hours to that timeframe.

Since hospitals only run a limited amount of tests, some healthy kidneys can be overlooked, Jaynes said.

“Which is unfortunate, but that’s how the system works right now,” he said.

The impact isn’t just at the patient level. Since 1973, Medicare has covered the cost of dialysis and kidney transplantation for patients with renal diseases, regardless of someone’s age. Now, kidney disease and transplants are a third of Medicare’s outpatient budget.

So far, 34 Lives has been able to get 83 kidneys to transplant surgeons who transplanted them into patients at nearly a dozen hospitals across the country, including in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Arkansas, New York and Massachusetts.

Sylvia Miles of Indianapolis received 34 Lives’ fifth kidney.

“I tell you, I feel amazing,” Miles said. “I haven’t had a flare up since I had the transplant, which is a great deal for me.”

34 Lives hopes to save 50% of seemingly unuseable kidneys over the next five years through their project, “No Kidney Left Behind.”

They recently received a $44 million award from the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, a federal investment agency.

“Imagine a future where we didn’t have to do dialysis at all because we had enough kidneys for everybody,” said Dr. Renee Wegrzyn, the director of ARPA-H at the time. “We can turn around somebody in crisis who needs a kidney [with]in days to weeks, then release that money into the economy.”

Although this research could move the needle, addressing the organ discard rate will only help a fraction of people who need a new kidney. Nephrologist Leonardo Riella said the issue also needs to be addressed in two other ways.

“One is reducing barriers for living donations so there are more living donors around,” Riella said. “And then, of course, is xenotransplantation. So looking for organs from other species that can be genetically modified to try to close the gap.”

But it could still be years before scientific research can lead to enough kidneys for every patient.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Elizabeth Gabriel is a health reporter with WFYI and Side Effects Public Media in Indianapolis, Indiana.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio–

SPEAKER 4: KKTV News.

SPEAKER 5: Iowa Public Radio News.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Local science stories of national significance. 37 million people in the United States live with chronic kidney disease, an illness where your kidneys, whose job is to filter waste from the blood, gradually stop working. At the end stage of the disease, patients rely on dialysis or kidney transplant to survive. But there aren’t enough donor kidneys for all the patients who need them, and even worse, for various reasons, some of the donated kidneys from deceased patients are thrown away. Around 9,000 of those donor kidneys were tossed last year.

But a lab in Indiana is trying to fix that. My next guest reported a story on their efforts. Elizabeth Gabriel is a health reporter for WFYI and Side Effects Public Media, based in Indianapolis, Indiana. Welcome to Science Friday.

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Hi. Thanks for having me.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, so the waitlist for getting a donor kidney is, on average, five years long. Tell me about the state of kidney shortages.

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: So over 700,000 people have kidney failure in the United States. The national kidney transplant list gives patients an opportunity to receive a kidney once it becomes available. Someone’s place on the list depends on their condition, but a national kidney shortage makes it hard to serve every patient. So only about 100,000 people actually make it onto the transplant list, and only a quarter of those people get a kidney each year.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Where did the donor kidneys come from?

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Kidney donations come from two sources, living donors and deceased donors. It’s possible to get a kidney from a living donor, like a family member or a friend. But only 6,400 living donations were made last year.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah, so why are so many kidneys thrown away?

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Great question. So about 9,000 deceased kidney donations were discarded last year, partially because transplant surgeons feared they wouldn’t work efficiently once transplanted. Transplant surgeons can get a small biopsy of the organ, run imaging, and collect medical information from the donor, but that isn’t always enough information.

That’s what Leonardo Riella told me. He’s a transplant nephrologist with the Massachusetts General Hospital.

LEONARDO RIELLA: These biopsies are processed very quickly, meaning we cannot do all the stains to look at all the different aspects of the kidney. So we may not be able to actually say what’s going on with the rest of the kidney because sometimes things can be spotty in terms of how they affect the kidney.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So you talked to a group of researchers in Indiana who are trying to solve this problem of some kidneys being thrown away. What are they doing?

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: So 34 Lives is a company in West Lafayette, Indiana, and they’re leading an observational study to try and salvage seemingly unusable kidneys. They hooked kidneys up to a life-support machine for 120 minutes, which allows 34 Lives’ staff to run nearly three dozen tests. Then they can determine how much sodium, potassium, and urine a kidney is producing. They also provide a kidney with nutrients like sugar so it’s able to heal itself.

Here’s what Chris Jaynes, the co-CEO of 34 Lives, said.

CHRIS JAYNES: That allows us to warm it back up to body temperature. We almost trick it into thinking it’s still inside a body, and it can start working and functioning just like it was inside a body still.

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: A typical kidney can stay outside the body for just 24 to 36 hours, but the company has added nearly 20 extra hours to that time frame.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow. That’s amazing. So these changes seem pretty straightforward. Why has it taken so long to make them?

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Yeah, hospitals don’t have the funds or resources to repair damaged organs. The Food and Drug Administration hasn’t actually approved a process for repairing kidneys. So if a hospital wanted to do something like this, they would have to conduct a research study, which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. That’s why 34 Lives is conducting this work under an observational study. They’ve received funds from donors, as well as a $44 million award from the federal government. The federal government has drastically cut research funding recently, but as far as they know, their award is still intact.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Did you talk to anyone who benefited from these changes?

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Yeah. I spoke with Sylvia Miles, who lives in Indianapolis. She has lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease that causes the body’s immune system to attack healthy tissue, including her kidney. Miles used to be in so much pain that she couldn’t even move, which meant she also couldn’t go to work. But she said everything changed once she got a kidney saved by 34 Lives.

SYLVIA MILES: I tell you, I feel amazing. I haven’t had a flare-up since I had a transplant, which is a great deal for me.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How much of the donor kidney shortage does this address? Like if the methods that 34 Lives are using were more widespread, would we solve the kidney shortage issue?

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Yeah, so 34 Lives hopes to salvage 50% of seemingly unusable kidneys over a five-year period. But even so, that’s only a fraction of the kidneys needed to serve all patients. So even though this could be a huge step forward, Riella believes there needs to be an increase in other kidney transplant methods.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s about all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Elizabeth Gabriel, health reporter for WFYI and Side Effects Public Media, based in Indianapolis, Indiana. Thanks for joining us.

ELIZABETH GABRIEL: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.