A Pandemic Precedent—Set in 1918

17:16 minutes

The 1918 flu has commonly been called the “Spanish Flu.” But it wasn’t Spanish at all. Listen to the origin of the name in an episode of the new Science Diction podcast!

The 1918 flu has commonly been called the “Spanish Flu.” But it wasn’t Spanish at all. Listen to the origin of the name in an episode of the new Science Diction podcast!

In the spring of 1918, a new and virulent flu strain was documented at a military base in Kansas. Within weeks it had been observed in Queens, New York—and soon, spread all over the globe. By the time the flu petered out a year later, the world had suffered three distinct waves, killing somewhere between 17 and 50 million people, and heaping a fresh disaster atop the losses of World War I.

In the United States, some people reacted poorly to public health measures, forming an Anti-Mask League, and refusing to stay home—complaints that may now feel familiar. End-of-war celebratory parades caused a grim increase in infections, which may seem like a warning against relaxing physical distancing measures too soon.

But how well does the present resemble history—and are we at risk of repeating the staggering toll of the 1918 flu? Historian Catharine Arnold talks to Ira about stories from the past, and the events and choices that drove additional waves of infection and death.

Plus, Science Diction host Johanna Mayer on why the 1918 flu wasn’t really ‘Spanish’ at all.

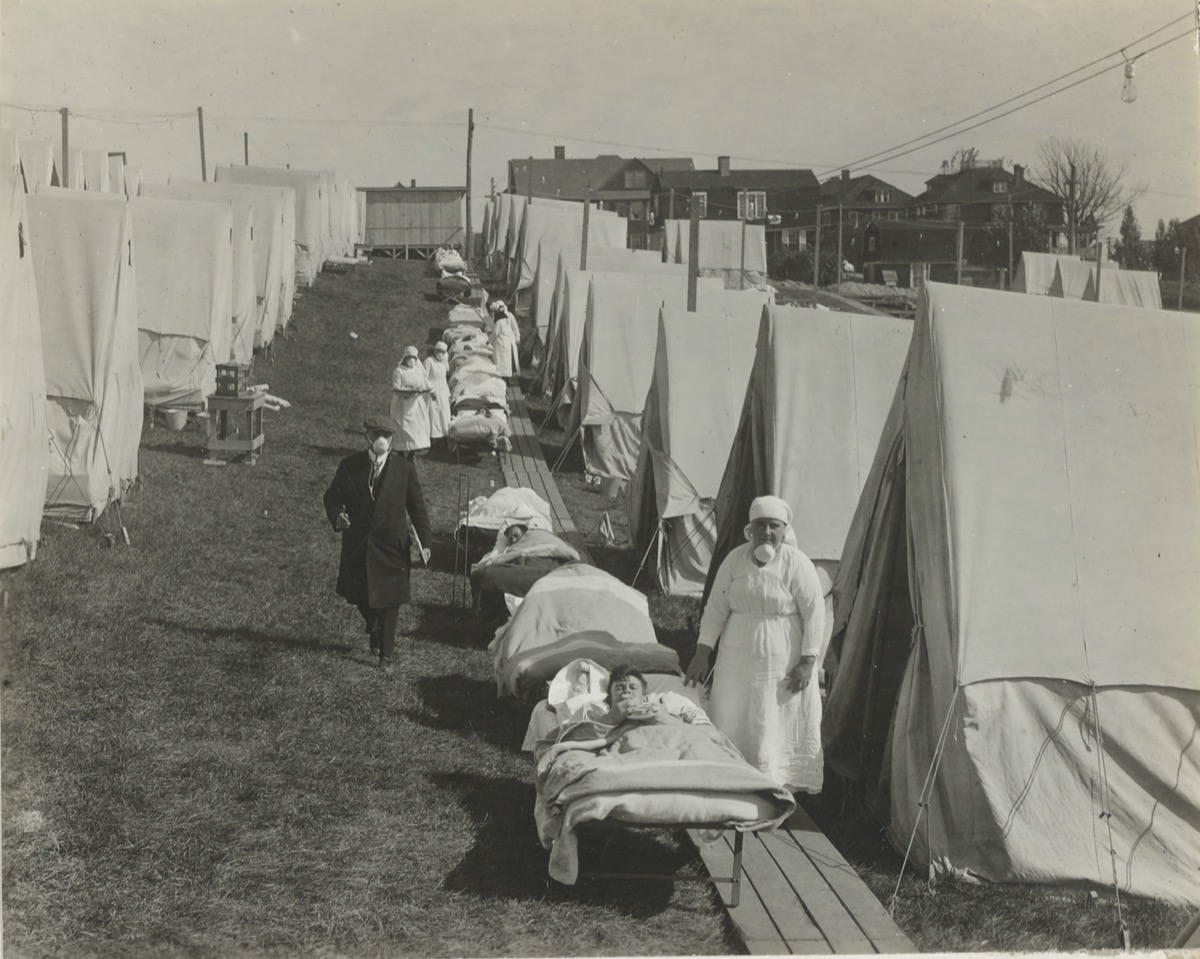

Look through images taken during the 1918 flu, from the U.S. National Archives, in a gallery article.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Catharine Arnold is a historian and author of Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. She’s based in Nottingham, England.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I am Ira Flatow. In March of 1918, soldiers at a military base in Haskell, Kansas began dying of an unusually deadly strain of influenza. A week later, the same illness was reported in Queens, New York and quickly proliferated into the worst global pandemic since the Black Death, killing tens of millions of people.

This strain of H1N1 flu virus would strike in three separate deadly waves around the world before petering out in the summer of 1919. We’re going to dig deeper into that horrific pandemic and its relevance today. But a good place to start is, well, let’s clear something up.

The 1918 pandemic was known as the Spanish flu, except it really wasn’t Spanish at all. Johanna Mayer is the host of Science Diction, our podcast about words and the science stories behind them. She’s here to explain where the misnomer came from. Welcome back, Johanna.

JOHANNA MAYER: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s talk about this. Give us the story behind this.

JOHANNA MAYER: Well, remember, the 1918 pandemic happened smack in the middle of World War I, so troops are moving around. That did not help things, because movement of troops obviously means movement of the virus. It’s kind of a nightmare. So Germany, the US, Britain– they were all seeing really horrific outbreaks of this flu.

But they did not want their enemies to know about that. Morale, the appearance of troops dropping like flies, weakness– not something that you want to let your enemies in on. But one country that didn’t have to worry about any of that was Spain, because Spain was neutral in World War I.

So when the virus hit Spain and even the king there got sick, the Spanish press did what basically any newspaper would do under normal circumstances, which is that they reported on this outbreak. And Spain was simply the first country to regularly and consistently report about this flu, and they got stuck with the name Spanish flu. And it stuck.

But the thing is, researchers aren’t totally sure where the flu actually originated. I think the jury is really still out on that. Some people say France. Others say the American Midwest. Some say China. But one thing that they’re pretty certain about is that it was not Spain.

IRA FLATOW: So I’m curious about what they called it in Spain.

JOHANNA MAYER: Good question. A bunch of places around the world had their own probably inaccurate names for this outbreak. So in Madrid, they called it the Naples Soldier, but in Poland they called it the Bolshevik disease. In Germany, they called it the Flanders Fever. And in other places it was sometimes referred to as the German germ. So basically, everyone had their favorite scapegoat for this outbreak.

IRA FLATOW: That’s terrific. It’s great that you’ve cleared all of that up. Thank you for dropping by to dispense those pearls of wisdom.

JOHANNA MAYER: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Johanna Mayer is the host of Science Diction, our new podcast that unearths the surprising origins of words and phrases in common use. And her newest episode is all about the 1918 pandemic, this so-called Spanish flu. You can find it wherever you get your podcasts.

And now, on to the rest of the story. As I said before, the 1918 pandemic killed millions. It tore through the globe in record time, left people wearing masks and social distancing. All that feels familiar, right? So is there something we can learn from that disaster?

Or is the parallel to the present just skin deep? My next guest is a historian, Catharine Arnold, author of the book, Pandemic 1918– Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. She joins me from Nottingham in England. Welcome to Science Friday.

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: We were just talking about how World War I was pivotal in the naming of the 1918 pandemic. But how did it contribute to the spread of the virus?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: I think the Great War, as they called it in those days, made an enormous impact. The Spanish flu would eventually spread around the world, in any case, just as the Black Death did and the plague in the 17th century. The difference was that all the troop movements turned the globe into a giant petri dish. So there wasn’t one continent, one area of the globe that went unvisited by Spanish flu, or as they sometimes fancifully called it, the Spanish Lady.

IRA FLATOW: So how fast did it actually spread around the globe?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: The big spread really came with the second wave in May, June of 1918. Before that, a strange new infection had sprung up, as was mentioned earlier, in the army camps and in some parts of the United States. And then it mysteriously disappeared, only to return in a second wave far more integrated and deadly towards the end of the summer of 1918.

IRA FLATOW: Was any one country hit the hardest by the flu?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Well, as I say, it spread around the globe. And certainly, the continental areas of India and Africa suffered particularly hard, because of the levels of poverty there and the subsistence levels of living. However, the US and Canada were also hit pretty hard.

IRA FLATOW: Was there any logic to which countries were hit the hardest?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Yes, on an international basis, I would say, and so would many other researchers in the field, that the countries which were hit the hardest were the poorest, the ones that were struggling economically that had very, very, very few resources to cope with the impact of a pandemic on this scale. Very few medical resources and a population already riddled with deprivation and disease.

IRA FLATOW: And what kinds of measures seemed to be the most successful in containing it?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: The most successful measures in containing it were almost identical to the ones being used today, and that is quarantine. And they didn’t have the term social distancing in those days. It had not yet been invented, but the concept was there.

For instance, in some parts of the United States, citizens were asked to undergo quarantine measures. Schools were closed– pool halls, cinemas, and theaters. But strangely, some large gatherings such as Liberty Bond drives and victory parades still went ahead.

IRA FLATOW: As you mentioned, there was the second wave of the flu. It wasn’t just one hit. But it actually got worse in the summer of 1918. Can you tell us? Why did that happen as far as the historians understand it?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: There are various explanations for this. I’ve never been able to come down with a tangible one. My best one– my best guess would be that in previous waves of flu, which have gone in waves of 1, 2, 3, the second wave has always been stronger and more deadlier than the last.

This may be because some citizens have already acquired immunity. But the virus evolved and picked off the youngest and the fittest. The most noticeable thing about the Spanish flu as opposed to coronavirus, which is more of a pneumonia, the Spanish flu attacked the young and the fit.

And the younger and the fitter you were– for instance, if you’re a young soldier or a pregnant mother, the more likely you were to become a victim. This is because Spanish flu set up an autoimmune reaction. And as your body fought off the virus, it quite often would kill you, too.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that is amazing. I think most people didn’t know that. It seemed that most deaths were occurring at the age of 28?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Correct. And of course, flu being the highly contagious disease, it flourished in barracks and prisons. And it flourished in urban areas with the highest level of the highest index of deprivation, places where people were crowded together in squalid conditions with few resources in substandard housing. So when I started this, I thought that Spanish flu would be pretty egalitarian in its approach to killing. But the more I researched, the more I realized that it was the poor and the sick who suffered most.

IRA FLATOW: But it eventually petered out. It went away. Do we know why that happened?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: The most compelling explanation for the way that it petered out would be a thing they call herd immunity, which is the idea that the more people become infected, the weaker the virus grows. Although, herd immunity has a bad rap at the moment.

Because it’s not, to my mind, the best way of containing the current outbreak pandemic. Herd immunity probably accounts for the way that Spanish flu petered out. As it became widespread, its impact became lessened. It became weaker.

IRA FLATOW: We are seeing some push-back by some groups who are against wearing masks and social distancing. Did that happen also with people in the 1918 pandemic?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Indeed. There were protests against quarantining, social distancing, and mask wearing. In San Francisco, an organization developed called the Anti-Mask League. And this was a bunch of physicians, public health experts, skeptics, and cranks who believed that masks were not necessary and in fact, might actually be deleterious.

The Anti-Mask League developed after the armistice. It developed with the least talked about third wave of flu, which had hit San Francisco in January 1919. The mayor, Mr. Rolf, and the chief officer of health– Haskell– said right, masks back on, people. We need these masks, because they will keep the death rate down.

So the Anti-Mask League not only refused to wear masks and said that they were unconstitutional and flew in the face of civil liberties, but one person who just named himself John sent an improvised explosive device to the government offices, saying here’s a present from me.

It was composed of an alarm clock, various bits of shrapnel and springs. And if it had gone off, it would have killed many, many people. Fortunately, it was defused. But this was some indication of the strength of feeling about being forced to wear masks.

In the end, what happened in the interests of democracy is that a petition was submitted to the local council. And the council ruled that, yes, it was no longer mandatory to wear masks. This was around– about January 1919. Mask came off. People got sicker. So it proved that there was some validity in wearing masks after all.

IRA FLATOW: So there really is and there are parallels between that pandemic and what we’re going through now in terms of social reaction to it.

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Oh, yes, I would say so. And obviously, having done all this research and published in the field, I was quite astonished when I saw the footage of protesters taking to the streets in the US with the “Give me liberty or give me death” slogans where it’s very easy to think, well, actually, if you take your masks off, death is just what you might get. So it’s strange to me. But I guess everybody feels that they have their own rights to consider and perhaps understandable, given the trauma that we’re all living through, the uncertainty.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. And this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking to historian Catharine Arnold about the pandemic of 1918. Interesting that a full third of the globe in that 1918 pandemic is thought to have been infected. Do you think we should be worrying that we might see this kind of history repeated?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Well, there are a number of explanations for this. I think that we will probably endure further outbreaks of coronavirus. In the Far East, regular outbursts of killer flu have become such a feature of daily life that it’s never surprising to see people, say, in mainland China wearing masks.

I don’t think this is a one-off. I think it will become a feature of our daily life, just the way that, sadly, terrorism has done. But I don’t think that we will suffer quite the mortality rate that they did in 1918 if only for the reason that we are a bit more prepared now.

We have more resources. And the majority of people seem to be taking on the slogans, and doing the social distancing, and staying home, and realizing that they have an obligation, a moral right not just to look after themselves, but to preserve the lives of those around them.

IRA FLATOW: Do historians view this as a really seminal event in their occupation? And are they taking special care to preserve records or to keep track of the events as they’re unfolding?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: I believe so. Yes, I certainly am. I think, overall, the great question is, how did this start? Who let this out? Where did it come from? And people will want those questions answered. And it’s also going to have an impact on research as well. After the Spanish flu, after World War II, there was an increase in research into infectious diseases and viruses of this sort. Well, that’s going to redouble now, because there’ll be a desire also to develop a vaccine.

IRA FLATOW: When your book first came out a few years ago, you were asked about the legacy of the 1918 pandemic, what it was. What did you say then? And how would you edit that now?

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Well, one thing I was asked to do, making a TV program, was basically to shroud wave. The producer wanted me to say that there would be another pandemic on the scale of Spanish flu or at least the biggest thing since Spanish flu. At the time, I was very cautious. Because I wanted to seem– I wanted to maintain a certain historical detachment.

Now, I can see that the pandemic has been worse than anything we could have envisaged. But suddenly, part of this is because in many, many Western countries, the preparedness was not there. The resources were not there to cope with an outbreak of pandemic pneumonia on this scale. And that’s for reasons of governmental decisions, and under-staffing, and under-resources.

IRA FLATOW: Before you go, I want you to tell me a little bit more about the story of the Manchester public parade that they had there, where health officials were warning against letting people congregate. Scientists were saying, don’t do it. And they went ahead and had this big parade anyhow.

CATHARINE ARNOLD: That’s absolutely correct. On armistice night on November 11, 1918, the chief– the medical officer of health told the council in Manchester, whatever you do, you must avoid mass gatherings to celebrate armistice, because this will result in a spike in the death rate.

The council ignored him, although they’d taken his advice in the past, and it had saved lives. So thousands of people poured into Albert Square in Manchester to celebrate the armistice. And a week later, the death rate had soared. And already, 300 people were dead. And the Manchester evening news said this is one of the greatest disasters that’s ever befallen Manchester.

And the saddest thing of all is that Dr. James Nevin, the chief medical officer of health, who had told the council not to allow this to go ahead, later killed himself. And it’s always been thought that he felt that he’d failed all those thousands of people who contracted it later on and died.

IRA FLATOW: What a lesson for the ages and, hopefully, history not repeating itself. I want to thank you very much, Catharine, for taking time to be with us today.

CATHARINE ARNOLD: Well, thank you for inviting me. I’ve had a really interesting time. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Catharine Arnold, a historian and the author of Pandemic 1918. She joined us from Nottingham, England.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.