Grade Level

6 - 8

minutes

1-2 days

subject

Chemistry

stem practices

Planning and Carrying Out Investigations

Activity Type:

History of science, After School Activity, nature

Have you ever walked in the shade of a mighty oak tree? In late summer or fall, you may find an odd little brown woody ball attached to a fallen twig. Look up into the tree, and you may see more attached to the twigs or leaves above you. Looking closely at these little wonders, you will probably find tiny holes all over them. What do you think these balls are? How do you think they are formed? You may be surprised by the answer!

Parasites Are The Culprits

The process of forming a gall begins when a wasp the size of a tiny gnat (see image below) lays its eggs on an oak tree branch. The eggs hatch, and larvae (also called grubs) emerge. Either the egg or larva secrete a mixture of starches, enzymes, and other compounds causing a chemical reaction to begin. This reaction activates a trauma response in the tree tissue. As a result, the tree starts to grow extra cells, which form a gall, a sort of cocoon for the wasp to grow into. The gall protects the wasp larva as it grows and provides food as well. Though the process is not fully understood by scientists, it’s very common. There are over 1,300 species of gall wasps worldwide!

This type of wasp is parasitic. It needs the tree to grow. Parasitic relationships are a type of symbiotic relationship. These kinds of relationships exist all over nature between insects and other insects, between insects and plants, and between insects and animals. A parasite needs a host for it to grow and live. In this situation, the wasp is the parasite that needs the tree to act as its host. The wasp’s actions irritate the tree but don’t kill it. The wasp needs the tree to survive. In this relationship, only the insect benefits while the tree is mildly harmed. Other types of symbiotic relationships include mutualism (mutually beneficial) or commensalism (mostly neutral).

Once the little parasitic wasp reaches maturity, it burrows its way out of the gall. The tiny holes you see on the surface of the gall are the escape routes for the larvae that grew up within it. Once the young wasps fly away, the gall is left behind, still attached to the tree. Eventually, due to the extra weight of the woody gall, it falls to the ground.

If this all sounds a bit gruesome, you don’t have to worry. Gall wasps don’t sting, and they can’t hurt humans. Although some entomologists warn against allowing too many galls to form on an oak, others see value in them. The galls serve as food for woodland creatures like squirrels, possums, raccoons, and birds. If you find gall halves on the ground, it may be the handiwork of squirrels who crack open the galls to eat the tiny larvae. Some birds also burrow into the galls to feast on the insects inside.

Oak galls come in a wide variety of sizes, colors, and shapes. One variety is called “oak apples” because of their red color. Some look like fuzzy little dots. Oaks are particularly susceptible to galls, but other species of trees get them too, including ash, maple, hickory, and spruce. Galls are caused by insects in oaks, but they may also be caused by fungi, mites, or even bacteria and viruses in other tree species.

Should We Conserve Parasites? Some Scientists Say Yes

The History Of Oak Gall Ink

As interesting as the process of creating an oak gall is, these little orbs can be used to create something even more fascinating. Oak trees and their galls contain a chemical called tannic acid. When this acid is mixed with iron (ferrous sulfate), it suddenly changes to a black color. The chemistry of the reaction is complex, but the process is simple—so simple that people have used it to make ink for centuries!

Pliny the Elder, a Roman encyclopedist of the 1st century CE, was the first to write about the chemical process used to create ink from oak galls, but the process didn’t become popular until centuries later. Other famous figures from history used oak gall ink to write their works, such as the engineer and artist Leonardo da Vinci and composer Johann Sebastian Bach. Physicist Isaac Newton had his own recipe that contained a rather odd ingredient: beer! Even the Founding Fathers of the United States used oak gall ink to write the Declaration of Independence. Paleographers, historians who study old writing, can identify the types of ink used in manuscripts through chemical analysis, so they can tell which writers used oak gall ink.

Even before Pliny, Philo of Byzantium, an ancient Greek engineer of the 3rd century BCE, used the chemical process behind producing oak gall ink to write secret messages. In his Compendium of Mechanics, he describes how when at war, “Letters are written on a felt hat on the skin after smashing gallnuts and steeping them in water. When they dry, letters become invisible, but if ‘flower of copper’ (or iron) is ground in water like black (ink) and a sponge is filled with water, when (the letters) are moistened with the sponge, they turn visible.”

Activity: Make Oak Gall Ink

Oak gall ink is pretty simple to make. Soaking crushed galls yields a brown-colored liquid that can itself be used as ink, but for a nice dark black ink that stains the paper more permanently, you’ll need to add iron. The chemical reaction that happens when ferrous sulfate (a compound that includes iron) is added to the tannic acid made from the galls causes the light brown liquid to suddenly turn dark black. It’s fun to watch!

Ancient people made ferrous sulfate by soaking iron (or things that contain iron, like nails) in water to force it to rust. These days, you can just buy ferrous sulfate at the store where it’s sold as a dietary supplement. You may also want to get gum arabic from an art supply store. It will help to thicken your ink, preserve the color, and bind it to the paper when it dries so that your creation lasts longer.

Materials:

- Oak galls from a tree or the ground

– If you can’t find them where you are, you can purchase them. - A mortar and pestle (but a hammer will do)

- A bowl

- A small jar or container

- A coffee filter (or cheesecloth)

- Hot water

- A spoon

- Ferrous sulfate dietary iron supplement tablets

- Gum arabic (optional)

- A stylus (a wooden manicure sticks work well.)

- Paper

– If you want to get fancy, order some real Egyptian papyrus! - Protective goggles or eyewear

Procedure:

- Collect galls from nearby oak trees. Look for older ones that have fallen to the ground. Older oak galls will have visible escape holes in them. These holes tell us that the wasps have already flown away, and we can be sure that we are not disturbing the life cycle of the gall wasps. You may even find some on leaves. They come in many shapes, sizes, and colors.

- Crush the oak galls in a mortar and pestle. If you don’t have one of these sets, a hammer will do. Regardless of your method, you need to wear protective glasses as bits of the woody galls may fly.

- Pour the crushed oak gall pieces into a bowl. Pour hot water over the gall pieces into your container. Leave to soak overnight.

- Set up a coffee filter or cheesecloth over a small jar or container. Pour the oak gall liquid over the filter to catch the crushed oak galls and strain the liquid.

- Crush a few tablets of the ferrous sulfate into a powder using the mortar and pestle or hammer. Add this powder to the container of oak gall water. The number of tablets you will need may vary by the brand you use and by the strength of your tannic acid solution. You will need to experiment to determine the amount of ferrous sulfate to add to get a dark ink.

- Stir the mixture with a spoon and observe. This is where the magic happens! A chemical reaction will turn the brown water into a black liquid.

- If you’d like to thicken the ink and make it adhere more easily to paper, add a tiny bit (1/8 of a teaspoon) of gum arabic. Once added, it can make the mixture extremely sticky so add cautiously. More can be added as needed. (optional)

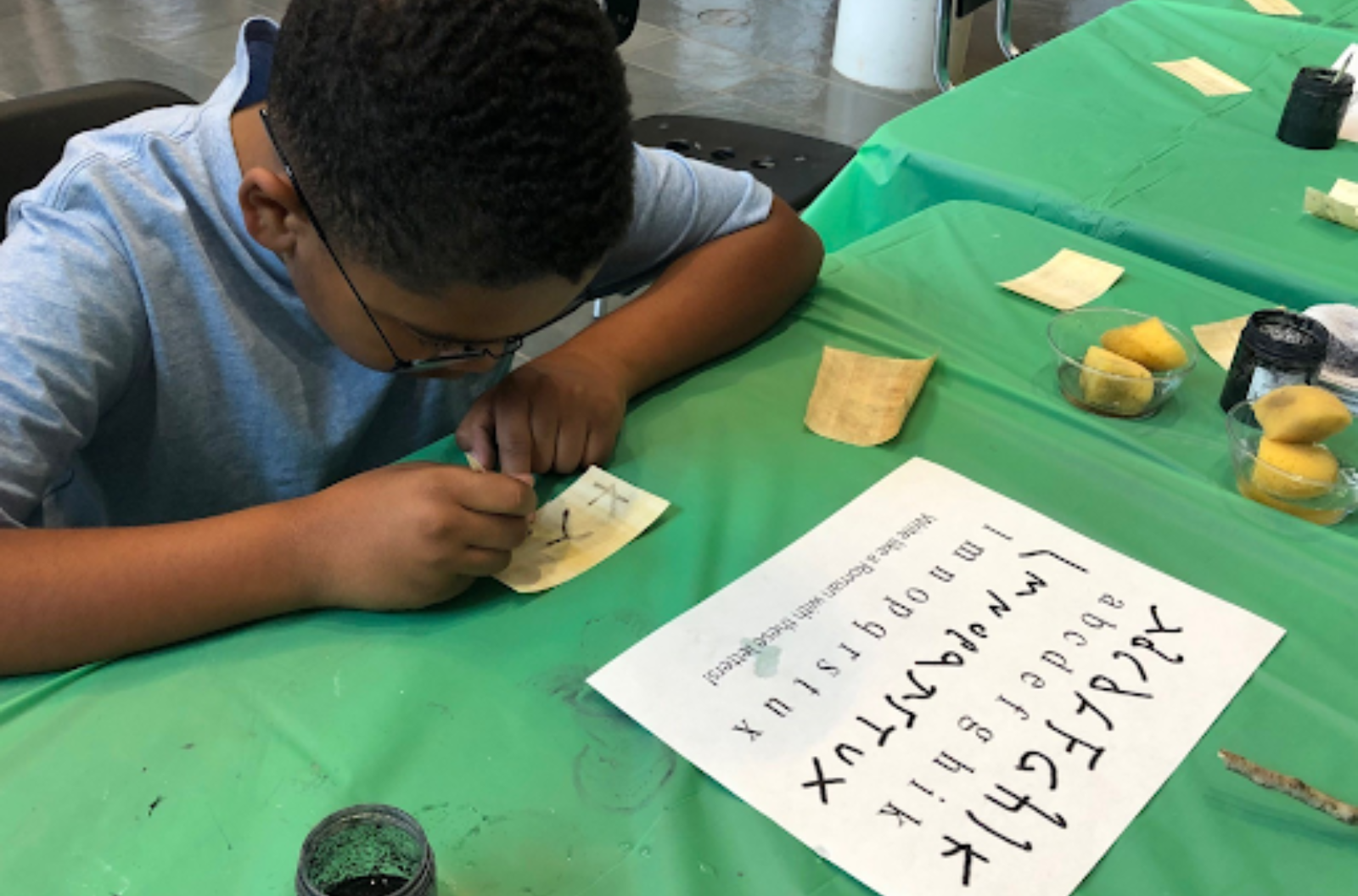

- Dip your stylus into the ink, and try writing with it. What will you create?

You’ll notice that the ink darkens after it adheres to the paper. This is the result of another chemical reaction between the tannic acid in your ink and the cellulose in the paper. Sulfuric acid is formed as a by-product of the reaction and will eventually corrode the paper with which the ink is used. Many manuscripts from hundreds of years ago have holes in them where the ink was used on the paper, and some have become illegible.

As you try out your new “old” ink, think about how people used it in the past. With all our modern writing tools, we sometimes forget how long it took to write things down and how messy it was. Erasing was done with a wet sponge. It took time for the paper to dry out before writing over the error.

Choose a poem to copy, or create your own, as you try out this process of writing with ink made from nature. We’d love to see what you make! Send a photo of your work to educate@sciencefriday.com, or use the form below.

How These Russian Wasps Could Help Save Ash Trees

Take It Further!

Want to learn more about making your own inks or how oak gall inks have been used throughout history? Try these resources:

- Dig deep into the science on the Iron Oak Gall Ink Website or in the article, “The Inky Story of the Dinky Oak Gall.”

- Discover the science behind preserving important documents, like the Declaration of Independence.

- There are many things around your house or in your backyard that you can use to make ink. The National Park Service suggests trying black raspberries, tea, or coffee.

- Making oak gall ink all started with sending secret messages. Learn to make other invisible inks and send messages to your friends.

- Entomologists are scientists who study insects. If the story of the oak gall wasp made you curious, you might enjoy the game “Pests and Beneficial Insects” from the Entomological Society of America.

NGSS Standards:

- MS-PS1-2: Analyze and interpret data on the properties of substances before and after the substances interact to determine if a chemical reaction has occurred.

- MS-PS1-3: Gather and make sense of information to describe that synthetic materials come from natural resources and impact society.

- MS-LS2-2: Construct an explanation that predicts patterns of interactions among organisms across multiple ecosystems.

Credits:

Lesson by Nathalie Roy

Developmental Editing by Sandy Roberts

Copyediting by Erica Williams

Digital Production by Sandy Roberts

Meet the Writer

About Nathalie Roy

Nathalie Roy teaches Roman Technology, Myth Makers, and Latin to young students at Glasgow Middle School in Baton Rouge, LA, USA.