Grade Level

6-12

minutes

1-2 days

subject

Earth Science

Activity Type:

life science, modeling, dinosaurs, art

Picture this. You’re out in sun-drenched territory in Morrison, Colorado. As you stop to close your eyes and take a deep breath in the searing heat and wipe another steady stream of sweat from your face, you notice a rock that seems a bit different. It’s hard to see it at first, but the color, texture, and placement seem a bit off in its surrounding. You clamber over the terrain separating you from this object of intrigue, keeping your gaze locked on the exact spot you noticed when you first opened your eyes from that deep breath. Now that you’re at the spot, you believe that your suspicions are correct. This rock seems to be more than just a rock. With your field gear, you begin to excavate carefully around the rock, slowly revealing what can be clearly identified as a fossilized jaw of some prehistoric creature. Excited that your amateur paleontological journey has paid off, you ask yourself while staring wide-eyed at your discovery, “What was this and what in the world did it look like?”

While we all may not be in that position in our lives, if you’re a fan of dinosaurs and other amazing prehistoric creatures, you may have imagined yourself in this situation. You could make the find of the century somewhere! You’re more likely to have this daydream after watching a documentary or Jurassic Park movie where these amazing creatures are brought back to life on the screen.

The question remains: How do those fossils go from that exhilarating moment of discovery to become a classified, named, and fully imagined drawing or computer model of a dinosaur? Between discovery and depiction, there is a lot of scientific sleuthing and artistic licensing that comes into play. Over the course of the past several decades, our understanding of dinosaurs has changed dramatically and so has their depictions. From bipedal, lumbering, tail-draggers to intelligent, complex, and sometimes feathered beasts, a lot has changed in our understanding of dinosaurs. How we depict dinosaurs has also changed to reflect these new understandings.

While it’s impossible for any scientists or artist to say that their understanding or recreation of a dinosaur is 100% accurate, science gets closer to this goal as new discoveries are made. Let’s take some time to dive in and see how the process brings these creatures back to life, from paleontologist to paleoartist.

Paleontologist

Paleontologists are scientists who study fossils of organisms. The study of these fossils ultimately helps us study the history of life on Earth. Not all paleontologists study dinosaurs. There is a myriad of different fields of expertise in paleontology, like micropaleontology, paleobotany, and invertebrate paleontology. Paleontologists study some of the largest creatures to ever exist on Earth like dinosaurs, all the way to the smallest microscopic plants and animals. This work takes place in a variety of places, from the lab to the field. Paleontologists use a variety of tools, whether they are extracting fossils from the Earth or using computer models to simulate the movement or vocalization of creatures. This work is incredibly important, not only because it tells us about life on Earth in the past, but because it also tells us an incredible amount about the creatures that exist today, how the world as we know it came to be, how Earth’s processes have changed the planet, how the climate has changed over time, and how these processes may impact humanity in the future. Even though not all paleontologists will agree about other things, they’ll all tell you that studying dinosaurs does in fact matter.

Going back to our fossil dream, how do these fossils go from being in the ground to places in our books or movie screens?

The Paleontologist’s Process:

Here is the process paleontologist would follow when a fossil is discovered in the field.

- Know your geographic location to know your geologic time location. Paleontologists want to know the geographic location so that they will be able to determine their geologic time location. North America, and the United States, in particular, is well-mapped in terms of what rock layers are exposed across the country. This information is readily available by the US Geological Survey. Knowing the rock layer and geographic location of your fossil can allow you to narrow down your search in terms of which organisms were alive during that time and how their environment may have looked.

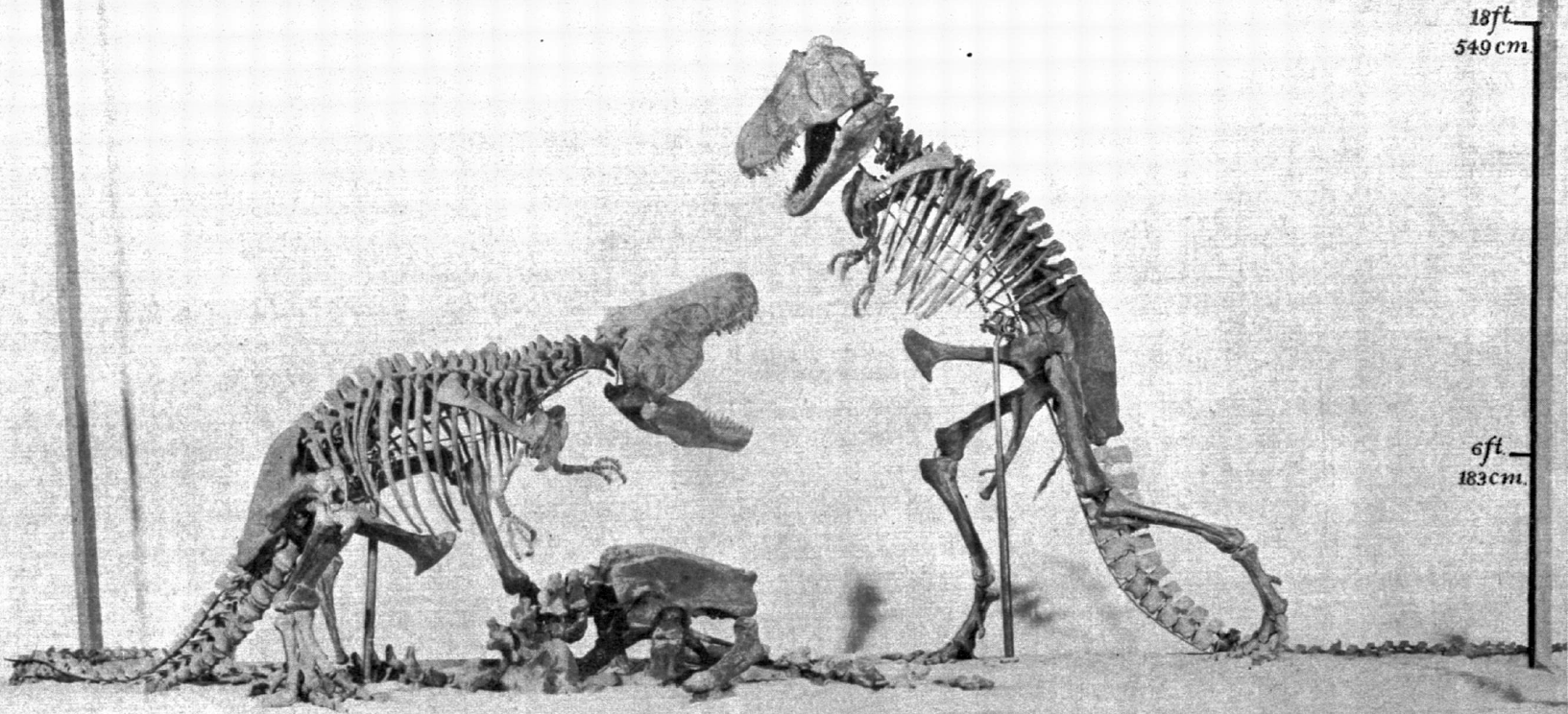

Our understanding of dinosaurs has come a long way from thinking dinosaurs were dim-witted, ferocious, lumbering, tail-draggers. Credit: Wikimedia Commons - An eye for clues. Careful observation of your fossil can lead you to a lot of very useful information. For example, the teeth in a fossilized jawbone can tell you the diet of your organism. This information can lead you to the part of the phylogenetic, or “family tree” where the dinosaur belonged. Phylogenetic trees are a way of visualizing evolutionary relationships between a group of organisms that share a common ancestor. A phylogenetic tree branches out as new species or groups of species are formed with their own unique traits. This can be incredibly helpful as members of similar branches of the tree will have similar traits. The phylogenetic tree on page 7 of your Dinosaur ID Guide shows which dinosaurs were alive and during what time. The names and numbers on the left side of the sheet indicate what era and how many million years ago they lived. You’ll notice that not all of the dinosaurs you’ve heard of are on the diagram. Some you’ve heard of before were alive during the entire age of dinosaurs. For example, Ceratopia, the group where the triceratops belonged, appeared first in the late Triassic at the earliest.

- Environment. Based on the location of the fossil and the relative age of the rock, you can learn about that location’s environment during the time that dinosaur was alive. The world has changed in an incredible amount of ways over time. Using Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Earth Viewer, move back in time to see a location and details about that location back when your dinosaur was alive. For example, the location of Los Angeles during this time period is no longer coastal area, but in a mountainous area. That type of environment could therefore be a potentially colder and rockier environment than exists there now.

- Look deeper. When there is very little fossil evidence, paleontologists take a much deeper look. Microscopic details in the structures of the bones can lead them in the right direction to identifying their dinosaurs. Minute details can mean big things to paleontologists, whether it be places for feathers to connect or channels for air sacs. Paleontologists also know the value of collaboration and what it means to support each as they make new discoveries.

Paleoartist

Paleoart is the artistic representation of prehistoric creatures that lived long ago. In the realm of paleoart, artists, in many cases, work to blend and compare the anatomy of existing animals, examples of creatures that are more well known, and anatomical structure from fossils that are as realistic as possible based on the information that’s available at the time. One such artist, Gabriel Ugueto, has taken his passion for the natural world and art and translated it into a career recreating dinosaurs and other extinct species for the public to see.

Gabriel has taken his passion as a herpetologist, someone who studies amphibians and reptiles, into the artistic realm. Using his knowledge, he’s developed his own method to recreate the fantastic organisms from long ago. Gabriel first looks at the bone structure to determine the shape of the organism. From there, Gabriel works outward to create the skin, scales, feathers, and color based on the time period and where the animal lived. Using all this information in concert, Gabriel creates his own interpretation of how the organism may have looked.

For the sake of our investigation, we’ll be sticking to the broader picture. Now that you have these details let’s begin to investigate! This is your opportunity to use some of the skills of a paleontologist, and a paleoartist!

Materials:

- Paleoart Student Notebook (Printable version or digital version for each student.)

- Dinosaur ID Guide (A digital version can be electronically shared with each student, or printed. Can be shared between a group of students)

- Morrison Formation Specimens (Students can print this out, or access an electronic version.)

Step #1:

- Pick one of the four Morrison Formation Specimens before you begin!

- Once you’ve chosen a specimen, be sure to note it on page 2 of your Student Notebook. If you’re using the electronic copy of the student notebook, copy over the images onto the page as well to make it easier to refer back to them in the future.

- These fossil specimens were found in the Morrison Formation Specimens. What does that mean in terms of how old your fossil is? Use your Dinosaur ID Guide as well as your own research about the Morrison Formation to help you learn more about the age of the rocks in the formation, then answer the questions on pages 4 and 5. Be sure to use specific evidence from the guide or your research to help you justify your answer. If you used information from your own outside research be sure to cite the source in your answer.

Step #2:

- On pages 6 and 7 of your Student Notebook, describe all the details about the fossil specimens that you can observe. Not all specimens have the same number of fossil images. If you have described all of your fossil images and have some additional blanks, you can delete them if you’re using the electronic version of the student notebook or simply cross them off or ignore them if you’re using a printed version. Remember, no detail is too big or too small when you’re making scientific observations. Write down every detail you see. When it comes to paleontology, each detail could be the difference between finding another specimen of a previously discovered species, reclassifying a specimen, or discovering a whole new species.

- Use your observations from pages 6 and 7 to compare to the Dinosaur ID Guide to help you hypothesize the identity of your dinosaur.

- Using page 8, create a claim based on the visual evidence you collected from your observations and comparisons you made in the dinosaur guide. Provide at least 3 specific pieces of evidence from the guide or your observations to support your claim.

- With the space provided on page 9 provide reasoning why each of the three pieces of evidence you provided support the claim you provided on page 8.

- Use your newly created hypothesis to conduct any outside research you may need into other critical details so that you can complete the outlines on page 10 and 11. For example, how long ago did your dinosaur live? What type of environment did it most likely live in? What type of food could have been a part of its regular diet? What type of color patterns may have been possible on its body based on all the information you gathered?

So What Does Your Dinosaur Look Like?

Materials

- Student Notebook (Print or electronic version for each student)

- Dinosaur ID Guide (Electronically shared with each student, or printed for each student. Can be shared between a group of students)

- Art Supplies (Pens, Pencils, Crayons, Markers, Rulers)

- Blank White Printer Paper

- Computer laptop, smartphone, etc. with internet access, capable of conducting internet searches.

Step #1:

- Watch Science Friday’s video about Paleoart and paleoartist Gabriel Ugueto so you can hear first-hand how a professional brings these creatures back to life.

- With your claims from the previous section, use your electronic device or prior knowledge to determine an organism alive today that might be somewhat similar to your organism.

- On page 14, describe why you believe that an organism fits as a living analog. Remember, the creature you’re trying to recreate is extinct, so don’t get hung up on the fact that no creature looks or would act exactly as you believe yours would.

Step #2:

- Starting with the skeleton of the organism as an outline, create the form of the body.

- Create an outline of the body structure of your organism here. Look at the examples from your guide, other research online, or in books that can help you create the shape and posture of your organism. Be sure to ask yourself questions such as how many legs did it walk on, did it have any large body features like horns, plates, or crests, and what position were its tail, head, or arms in when it moved.

Step #3:

- Add skin and color based on the environment and when the organism lived.

- Using something as a backlight, such as a flashlight or a window, sketch your organism from Part #1 on the previous page here. Test out your different color patterns and options to decide what best fits your organism. Use multiple versions of this page if need be. If you’re doing this electronically paste an image of your drawing here and try out your different colorations.

Step #4:

- Consider the size and body shape of your organism. Would your organism, based on the information you have and the environment, have been slender and agile? Covered in feathers? Have larger fat deposits to stay warm in marine environments?

- Using the same technique for recreating your creature’s outline in Part #2, create a sketch of your organism with the color scheme you chose. Now apply the appropriate environment to complete your paleoart. Be sure to keep in mind your earlier research about what it ate, the environment it lived in, the shape of its body, and other features that might give you a clue to how it lived and where it lived.

If you’re having a bit of creative block, use the example on page 20-22 to inspire you!

Reflection

Now that you’ve created your organism, put it into words.

- Describe the skin and features of your dinosaurs. What should it look like, what features should it have, and why? EXAMPLE: Does your creature have feathers? Did your creature have scales? Did your creatures have crests or other ornamental features?

- What should the skin color(s) be for your organism? Is there any type of pattern, coloration, or camouflage that your creature would have? Describe the features it should have and why, based on your research and observations.

- Why do you think artistic depictions of organisms like dinosaurs have changed so much over the past 100 years?

- In your opinion, why do paleoartists today create such a wide range of depictions of the same organism if the same information and research is available to everyone?

- What was the most difficult part of creating paleoart of your organism?

- Knowing you can’t hop in your time machine to find out if your paleoart is 100% accurate, what piece or pieces of information do you wish you could find to make your paleoart more accurate?

- How did the experience of this project change your ideas about the importance of fossil evidence in understanding our environment today? Use evidence from your experience to help support your point.

- How did the experience of this project change your ideas about the importance of fossil evidence in understanding creatures that are alive in the modern day? Use evidence from your experience to help support your point.

Standards

Next Generation Science Standards

3-LS4-3. Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity

Construct an argument with evidence that in a particular habitat some organisms can survive well, some survive less well, and some cannot survive at all.

HS-LS1-2 From Molecules to Organisms: Structures and Processes

Develop and use a model to illustrate the hierarchical organization of interacting systems that provide specific functions within multicellular organisms.

3-LS4-1 Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity

Analyze and interpret data from fossils to provide evidence of the organisms and the environments in which they lived long ago.

MS-LS4-2 Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity

Apply scientific ideas to construct an explanation for the anatomical similarities and differences among modern organisms and between modern and fossil organisms to infer evolutionary relationships.

Common Core English Language Arts Standards Writing

WHST.6-8.8

Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources; assess the credibility of each source; and quote or paraphrase the data and conclusions of others while avoiding plagiarism and providing basic bibliographic information for sources.

National Art Standards

VA:Cr1.2.7a

Develop criteria to guide making a work of art or design to meet an identified goal.

Thanks to:

ReBecca Hunt-Foster and the Dinosaur National Monument

Brandon Peecook of the Chicago Field Museum

Jim Kirkland, Utah State Paleontologist

Thomas Carr of Carthage College

Beverly Owens of Kings Mountain Middle School

Educator's Toolbox

Meet the Writer

About Brian Soash

@BSoashBrian Soash was Science Friday’s educator community leader. He worked to connect educators, schools, and districts with the outstanding educational content being developed by Science Friday.