‘You Press The Button.’ The Rest Is History.

You thought the hand-wringing around cell phone cameras was bad? Learn how controversial even adding a button to cameras was in this excerpt from Rachel Plotnick’s “Power Button.”

The following is an excerpt from Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing by Rachel Plotnick.

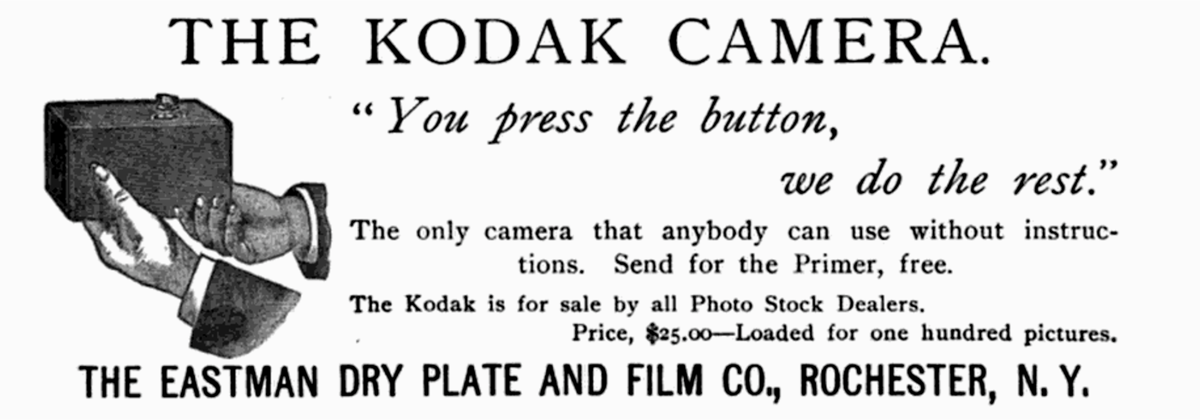

As with consumer technologies such as vending machines and elevators, a push-button mechanism on consumer cameras also attracted to the field of photography a new set of users who desired a more automatic and self-service experience without any requisite skill set. Through a catchy and direct tagline, “You press the button, we do the rest,” Kodak cameras appealed to potential consumers by heralding buttons as beacons of simplicity and automaticity—just press the button and let someone else deal with what happened next. The slogan served as one of the most popular anthems of the time period. One author noted that the phrase “is heard on the street, in the cars, at the theatre, in the clubs, and, in fact, wherever men and women most do congregate. The comic papers have burlesqued it, statesmen have paraphrased it, and it is repeatedly used to point a moral or adorn a tale.” Another editorialist called the statement the “prophetic cry of the age” because it spoke to one’s ability to summon anything—and anyone—with a touch. Recognized as one of the most effective advertising campaigns of its time, an advertising monthly journal interviewed George Eastman to understand how the phrase achieved so much success that “it has come to be common property, and is applied in every-day conversation everywhere.” In the article, Eastman noted that he never imagined how widely the phrase would take hold and could only offer in the way of explanation that he modeled it after the idea that, most basically, pressing the button represented the only work required of the camera’s user. The popularity of Eastman Kodak’s phrase in a wide variety of contexts indicates how the button served as a symbol of consumption, and pleasurable control of use for its users. As a catchphrase, “You press the button” tried to remove all previous assumptions that consumers might have about photography, refiguring the enterprise as a hobby made for amateurs who need not fear the camera, its mechanisms, or the effort involved in producing or developing a photograph. By removing labor from the photography process and by putting the working parts of the camera at a distance from the photographer, Kodak offered a model of digital command that relied on pushing and effects.

Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing

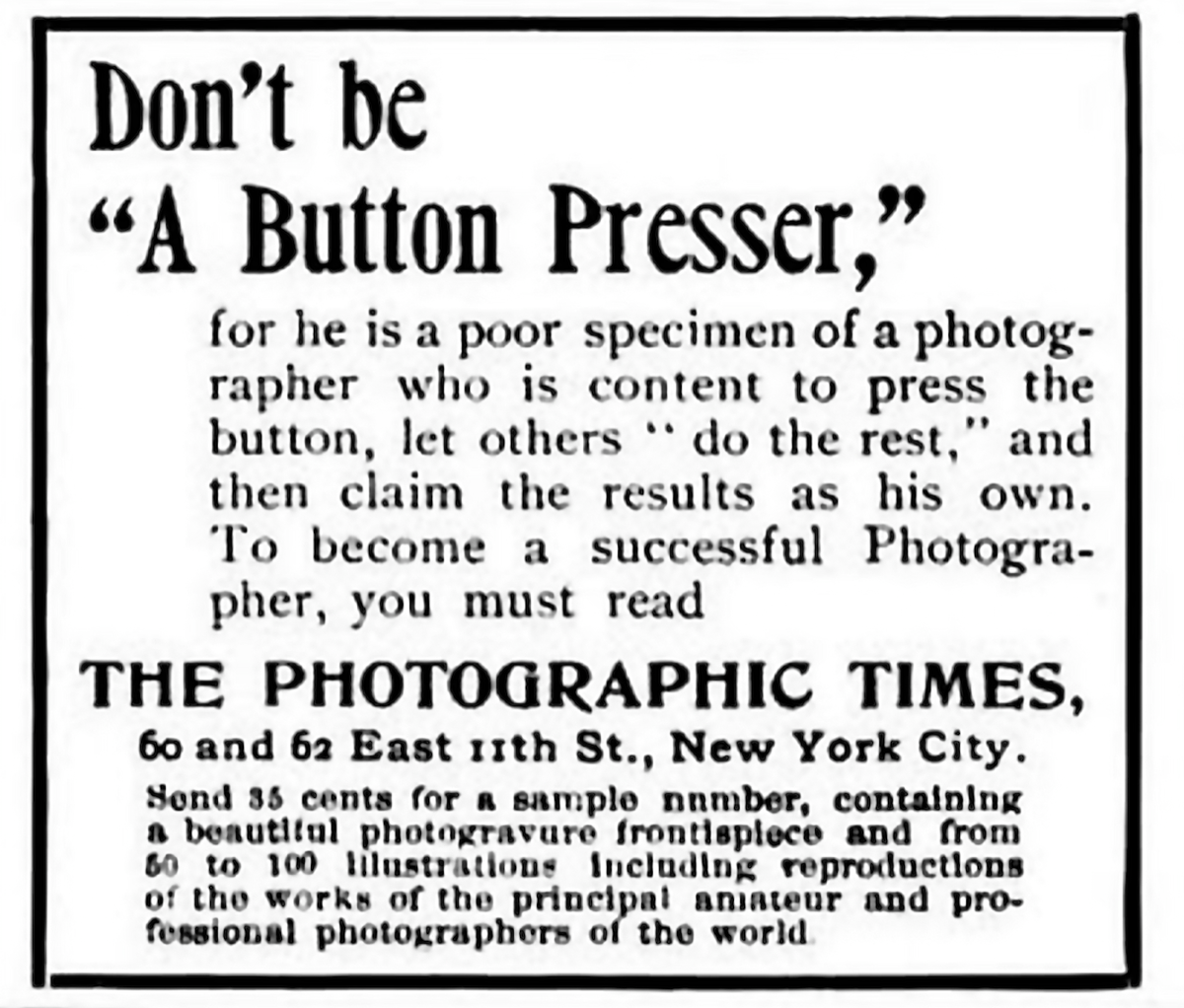

Despite the slogan’s clear success, this push-the-button mantra generated an irate response from those who felt threatened by the simple mechanism’s invasion of a once skilled craft, invoking concerns similar to those that manifested in discussions about doing away with elevator operators, shop clerks, or factory workers and in debates about push-button managers as nonworkers. In reaction to the campaign, a large ad in McClure’s magazine read (1896), “Don’t Be ‘A Button Presser,’ “for he is a poor specimen of a photographer who is content to press the button, let others ‘do the rest,’ and then claim the results as his own” (see figure 5.6). The stinging reproach, taken out by Photographic Times magazine, appeared in hundreds of publications at the end of the nineteenth century and criticized a growing number of amateurs using Kodak cameras. Boiling over into a variety of editorials and how-to manuals about photography, this tirade against button pressers served as a direct affront to the Eastman Company’s product and associated tagline. Professional photographers feared the rise of “you-push-the-button automatons” in their profession who would replace photo developers and make skilled workers unnecessary. On one level, Photographic Times’ antagonism toward the Kodak camera and its button helped to promote the magazine on the coattails of a well-known gimmick; on another level, however, it expressed a real anxiety at the turn of the century about push buttons and the kinds of interactions they facilitated with machines. For some, both within the photography community and well beyond it, button-pushing behaviors represented the dangers of letting machines replace human ingenuity, skill, craftsmanship, and effort.

Photographic Times’ public admonishment of the Kodak camera advertisement garnered attention within photography and advertising communities for its bold approach. One editorialist took the magazine to task for its criticisms, arguing that the Times “had no right to assume that every person who had his developing done by a professional was trying to get credit for the performance of some one else” and that “surely a man is not to be regarded as ‘a poor specimen of humanity’” because he desired this mode of photographic production. This advertising expert perceived the ad as an unfair attack against Kodak hand camera users, whereas professional photographers by and large embraced the notion that pressing a button had nothing to do with the art of taking or developing a photograph. Photographers cast aspersions against button pushers along a number of fronts, deeming them “careless, slovenly” individuals who could not be expected to imbue a photograph with “the emotions of a man’s soul.” These insults equated buttons with laziness and the kind of thoughtless behavior that existed in direct opposition to art making. The hand camera and its button threatened these individuals’ livelihoods, opening the doors of photography to a new class of amateurs previously shut out from the expensive, time-consuming process of developing pictures. Although unsurprising that this rank of consumers would attract vehement reproaches on the part of work-a-day photographers and developers, it is more interesting to note the ways that buttons grew entangled in such a debate. Photography experts did not blame the camera, but rather its button, for encouraging automatic (and therefore dangerously simple) photography. The button came to serve as an emblem of the camera, its push representing the opposite of photographers’ values and ethos.

At various points at the end of the nineteenth century, voices cropped up in support of button pressers, and as consumers increasingly took up the Kodak, photographers and developers were forced to come to terms with a change in the industry. In a stirring editorial titled “A Plea for Button-Pressers,” one author wrote, “When all is said and done, the sun takes the photograph, not we, and whether we put in a holder, draw a slide, remove the cap, count four, or only press the button, we do not ourselves really and truly displace the silver particles on the gelatin. … Why draw a hard and fast line between drones and busy bees at the mere development of a plate?” Once again, questions of effort and authentic engagement stood at the heart of this debate: Did pushing a button diminish one’s accomplishment or, as the writer suggested, merely combine steps in a process not entirely carried out by the photographer in the first place? Masking and even eliminating parts of the photographic enterprise, push buttons catalyzed concerns over whether simplicity stood in opposition to quality and true handicraft.

Excerpted from Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing by Rachel Plotnick, © 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Rachel Plotnick is the author of Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing (The MIT Press, 2018). She’s also an assistant professor of Cinema and Media Studies at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.