The Feat Of Building The World’s Largest Telescope

The Extremely Large Telescope is under construction on a mountaintop in Chile’s Atacama Desert. It could revolutionize astronomy.

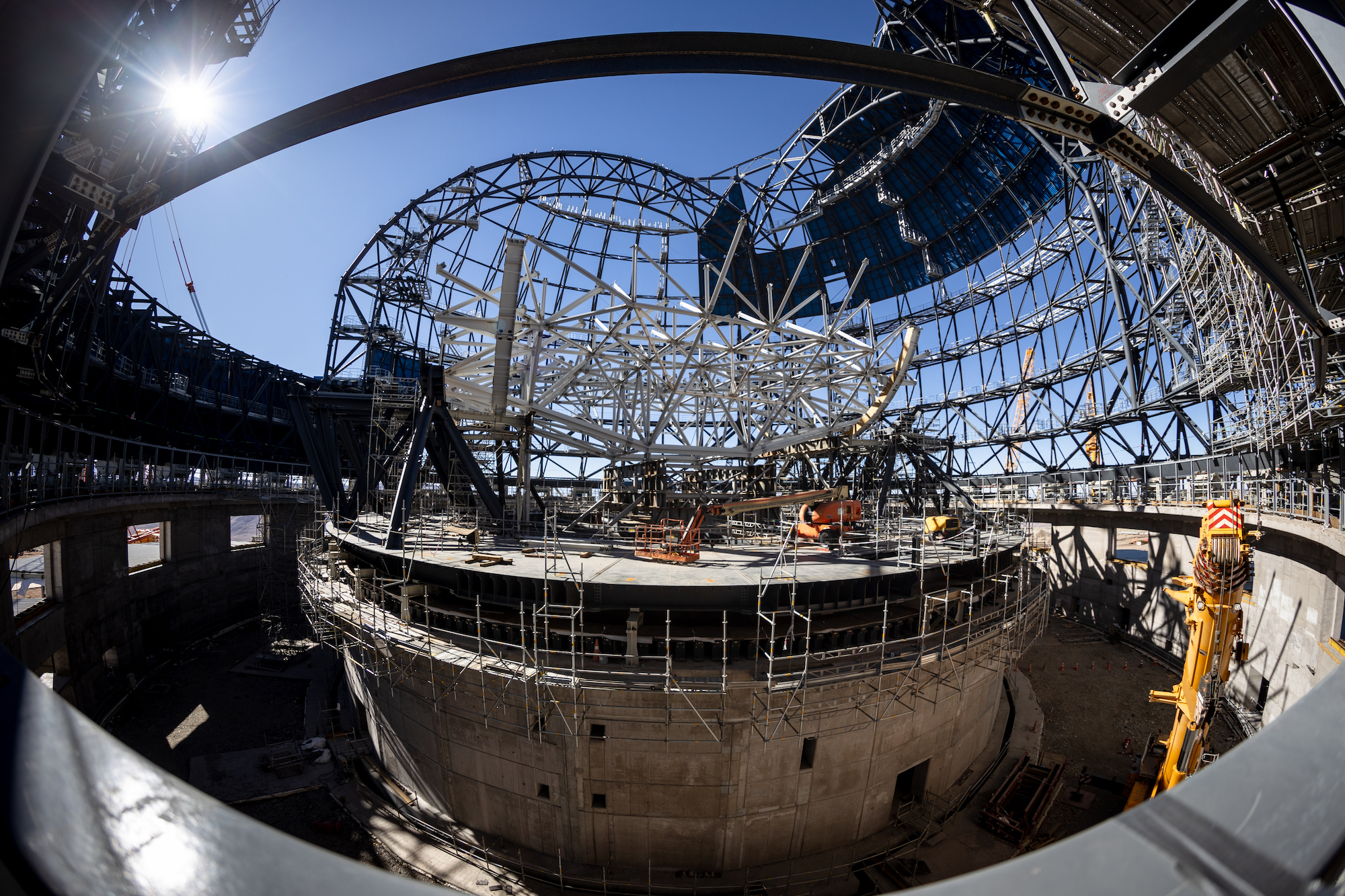

An interior view of the construction on the Extremely Large Telescope in Chile on May 8, 2024. Credit: Sofía Yanjarí

This story was produced by Science Friday and América Futura as part of our “Astronomy: Made in Latin America” newsletter and series. It is available in Spanish here.

In the remote Atacama Desert of northern Chile, an ambitious project is underway that could revolutionize astronomy: the construction of the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). Dubbed “the world’s biggest eye on the sky,” this colossal instrument is part of the European Southern Observatory (ESO)—an organization comprising 16 European countries as members, plus Australia as a strategic partner and Chile as its host—and is designed to probe the mysteries of the universe.

With a primary mirror that measures 129 ft in diameter, this will be the largest visible light and infrared telescope on Earth. Dr. Luis Chavarría, astronomer and ESO representative in Chile, says the ELT’s operations, which are scheduled to begin in 2028, could lead to a paradigm shift in our perception of the universe—a milestone similar to what Galileo achieved 400 years ago with his telescope.

The telescope is expected to help address the most complex questions in modern astronomy. Chavarría says it will allow researchers to study black holes in detail as well as the first galaxies that formed in the universe and dark energy and dark matter. The ELT could help scientists locate Earth-like planets, and potentially be the first telescope to find evidence of life outside our solar system, he says. “It will take us beyond where we’ve ever been before. Of course, its power will lead to unexpected discoveries, new areas of research, and questions that we are unable to ask today,” Chavarría says.

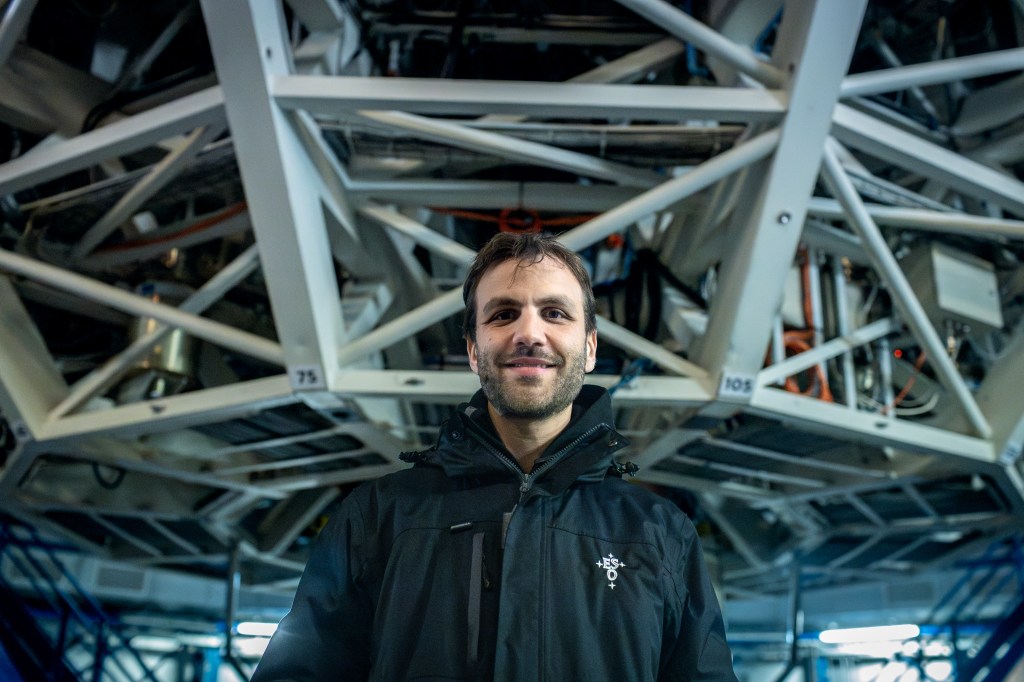

It will outperform the James Webb Space Telescope, which has discovered some of the longest-lived galaxies, because it will be able to capture images five times sharper due to the size of its primary mirror. “The bigger a telescope is, the more detail we can see in the universe,” says astronomer Dr. Michaël Marsset, who has worked at ESO’s Paranal Observatory since 2021.

Location is key when looking at the stars, and the Atacama Desert has become a veritable constellation of technology, thanks to its uniquely dry, and hence clear, atmosphere. It is massively attractive to astronomers, and is home to a network of telescopes, including ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), which is 14 miles from the ELT building site.

And so, the world’s biggest eye was destined to appear in the middle of this arid desert—a place where the Milky Way illuminates the night sky, and the dunes seem endless. But it also seems destined to be awe-inspiring. Its unfinished metal dome looms from the top of Mount Armazones, 10,000 ft above sea level, catching the eye of people passing by on the highway some 12 miles away.

However, Marsset explains that ELT’s cloud-topping height won’t be enough–it will also need adjustable mirrors, both on the telescope itself and its instruments, to compensate for image distortions caused by atmospheric turbulence.

This work has been an enormous feat of engineering, although, within ESO, they say you must think big to overcome the limits of science. Because its size makes it impossible to build in one piece, the telescope’s primary mirror, one of five and identified as M1, will be made up of 798 ceramic glass hexagons joined together like a honeycomb.

Tobias Müller, ELT’s on-site assembly, integration, and verification manager, inspects the coating of the M1 mirror segments in a large room of a building in Paranal. He wears a cap, mask, gown, and surgical gloves to avoid carrying any airborne contaminants. “It’s like an incubator (for the pieces),” he says. “Between entering and leaving the room, this whole process takes about 8 to 10 hours.”

Müller, and his team manage to process two segments a day. The goal is to give the fragments a highly reflective finish. Once the pieces leave the room, they are stored until installed. So far, however, only the 2,500-ton metal dome structure that will protect the telescope has been erected.

The extreme desert conditions can pose challenges during construction. A site supervisor, Marco Bravo, measures the wind speed to ensure that gusts do not endanger the dozens of workers inside the dome. “To make progress, at least on the facade, we have to take advantage of when the winds die down,” he says.

In many ways, bad weather can be costly, says astronomer Marcela Espinoza, an operator of the telescopes and instruments at Paranal, who monitors weather conditions as part of her job. Although she has specialized instruments to predict rain, she also uses what she calls her official machine: the human eye. That’s why in the evenings, she occasionally leaves the observatory to watch the clouds. If it looks like bad weather, protecting the telescopes always comes first.

The same treatment will be applied to the ELT once it’s up and running. “We have high expectations–hopefully I will also get my turn (to monitor it),” says Espinoza. Construction began in June 2014, but work slowed down for two years due to the COVID pandemic, and the project is now more than 50% completed.

For Italian Davide Deiana, ESO’s deputy site manager, the ELT is awe-inspiring not only for its technological advancement but also for its structure. “It’s like Chile’s own Colosseum,” he says.

This is not his first involvement in an astronomy project. He had already worked at the ALMA observatory in Atacama which, among other milestones, has documented the birth and death of stars, thanks to an image of a galaxy formed 600 million years after the big bang.

Based on his experience, he is convinced they are building an unprecedented work: “Everything is well-planned. This will be revolutionary.”

This story was translated from Spanish by Laura González.

Maolis Castro is a reporter for El País based in Chile.