What Your Lips Might Say About You

Researchers are studying what lip prints and other subtle physical traits might reveal about the etiology of cleft lip and palate.

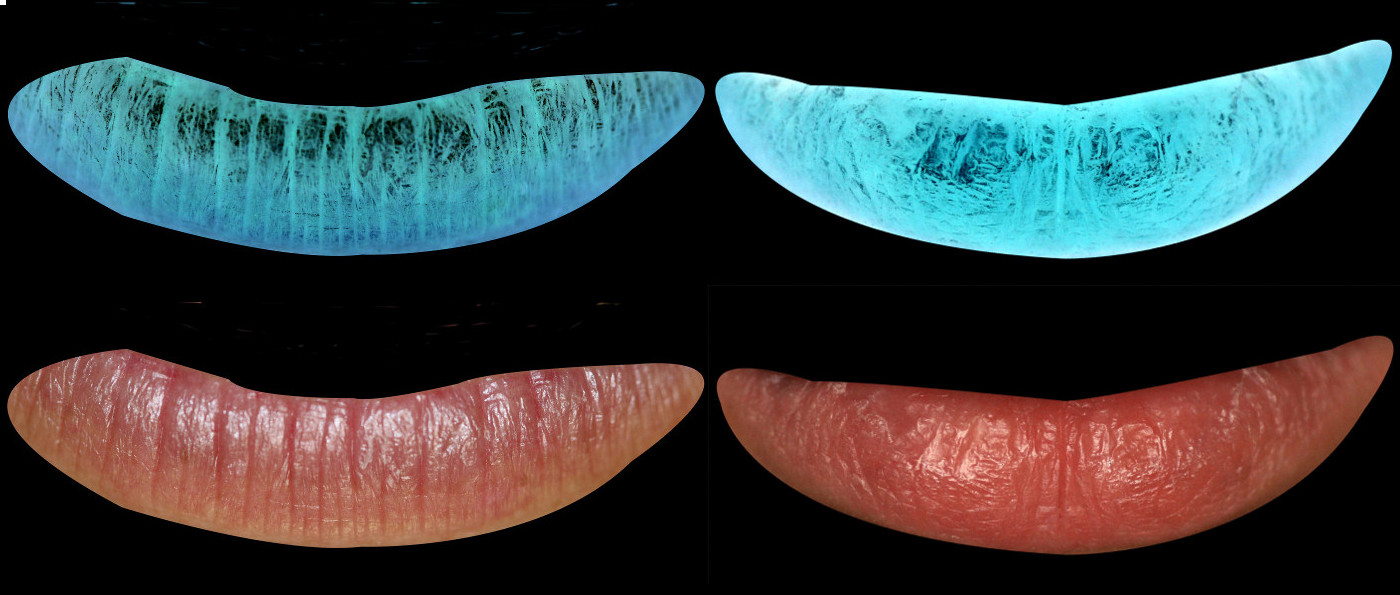

Notice any differences between the lips on the left and on the right?

Every single person sports a pattern of lines on their kisser. They’re laid down early in development and stay essentially unchanged throughout life.

“Lip prints are very much like fingerprints,” says Mary L. Marazita, a professor in the Department of Oral Biology at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Dental Medicine. “They’re unique to a person.”

Still, lip patterns can be broken down into several broad categories. There’s “straight and vertical,” like the photos at above left. Branching patterns, meanwhile, entail grooves that give way to more grooves, like limbs growing from a tree trunk. Some people’s lip lines crisscross like mesh. And others’ form circular patterns called whorls, like what you see in the photos on the right.

While they may seem incidental, prints on the lower lip are of particular interest to Marazita and her colleagues. They’re studying the etiology of clefts of the lip and of the palate, which are some of the most common birth defects in the world, affecting one in 700-1,000 babies worldwide. As part of their research, they’re investigating subtle physical traits that seem to occur in both people with cleft and in their unaffected relatives, and which could reveal deeper insights into the genetic underpinnings of cleft.

“We are not at the point yet when we can assign individuals or families to different genetic subtypes,” says Seth M. Weinberg, an associate professor of oral biology also at the University of Pittsburgh, who works with Marazita. “We believe the rich phenotyping approach we are pursuing, where we look at a wide variety of traits in cases and their family members, may help us get there.”

Clefting occurs early in development, during the first trimester. At about six weeks, a developing baby’s face starts to materialize as body tissues and cells grow from either side of the head toward the center to form features like the mouth and lips. If those tissues don’t join properly, clefts in the lip or the palate, or both, can occur.

“You have to appreciate the exquisite complexity that goes into forming a face. I mean, you’re talking about an embryo the size of a grain of rice, and there are these really precise events that have to happen, where tissues have to approximate each other, meet, fuse into sort of three-dimensional space, and it all has to be coordinated and happen with a very fine degree of precision,” says Weinberg. “This is why clefting is so common, because there’s so many places where you can go wrong.”

The likelihood that a fetus will develop an oral cleft of some sort is, in many cases, both genetically and environmentally dependent. Scientists have so far identified at least 15 or 16 genes that play a role, according to Marazita, who’s also the director of the Center for Craniofacial and Dental Genetics at the University of Pittsburgh.

“We’ve made a lot of progress, but there are still things that really puzzle us,” she says. “There are people who are carrying those risk genes but [who] do not express the birth defect. On the surface, they seem perfectly normal.” But they might bear certain traits that speak to an underlying risk.

A couple studies have suggested that lower-lip whorls could be one of those traits. During the 1970s, a German researcher named Von L. Hirth authored several papers investigating lip features and observed that the frequency of lower-lip whorls was higher in individuals with isolated cleft lip, with or without cleft palate, as well as in their families. (Isolated, or nonsyndromic, cleft does not occur with other birth defects, unlike syndromic cleft.) [Note: If your lips appear to have whorls, you do not necessarily carry risk genes for cleft.]

“You have to appreciate the exquisite complexity that goes into forming a face.”

More recently, in a study published in 2009 in the American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, a team led by Marazita found more reason to suspect that whorls are associated with clefting. They collected lip prints from 450 people with non-syndromic cleft lip, with or without cleft palate; their relatives; and unrelated control subjects from the U.S., Argentina, and Hungary. When they applied a narrow definition of “whorl,” the researchers found that the frequency of circular patterns in American individuals with cleft and in their relatives increased significantly, compared to controls. (No such association was found in Argentinians, and Hungarians showed no definitive whorl on their lower lips.)

Marazita and colleagues are continuing to collect lip prints from participants in various countries, including the Philippines, Nigeria, Colombia, and Puerto Rico, which they’re analyzing for further evidence of an association between whorl frequency and clefting, and “to see if we see the same phenotypes showing up in diverse populations,” says Marazita.

The “prints” the researchers are gathering are actually high-resolution photographs that they inspect specifically for whorl patterns. “We have three people independently review each image and score it, and then we use a ‘majority rules’ for the final rating of the image,” explains Weinberg. (In their 2009 study, the team did record actual prints on light-sensitive paper using a chemical placed on participants’ lips, but it didn’t “taste too good,” says Marazita.)

In addition to lip prints, Marazita’s team is also analyzing craniofacial features, such as dental characteristics and the musculature of the upper lip, as well as speech patterns, among other traits, to see what combinations of cleft-associated phenotypes occur in different groups of people, and to what degrees of prevalence.

From a genetic counseling perspective, this approach could eventually “help to identify relatives [of people born with cleft] who don’t themselves have clefts but who may be at increased risk for having a child or another relative with a cleft,” says Jeff Murray, a pediatrician at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine who has collaborated with Marazita and Weinberg for many years.

Last year Congress gave Marazita and her colleagues a funding boost, which they’ve put towards sequencing the entire genome of more than 400 sets of families (which each include a child with cleft and an unaffected mother and father). “It’s the first time that whole-genome sequencing on a large scale has been applied to cleft lip and palate,” says Marazita.

Once they dive into the results, they’ll be able to learn more about the genes that drive clefting, as well how they relate to what appear to be associated phenotypic traits. And maybe then they’ll have a keener sense of just what those lip prints are saying.

Julie Leibach is a freelance science journalist and the former managing editor of online content for Science Friday.