Welcome To The Emotion Arcade

A new generation of video games engages complex emotions like empathy, complicity, and grief. Game researcher Katherine Isbister gives a newbie gamer a tour of the “Emotion Arcade.”

Confession: I am not a gamer. The sum total of my gaming experience is an intense, elementary school obsession with Oregon Trail. You won’t find Candy Crush on my phone, and my thumbs fumble around the simplest game controllers. But I would love for this to change. Why? Because as game researcher Katherine Isbister argues in her new book, How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design, the emotional experiences that today’s games offer are often complex, sophisticated, and satisfying.

“I think a lot of people have in their minds something that’s really a 10- or 15-year-old vision of gaming,” Isbister explains. They picture “somebody by themselves, shooting things, staring at the television.” And that’s too bad, because today’s games can often have “more shades of grey” and “more mixed, ‘grownup’ emotions to offer,” Isbister says. “You might compare them to the more sophisticated media experiences of cable or Netflix series, as opposed to a Hollywood action film.” Who wouldn’t want to try that?

On April 1, Isbister, a professor of computational media at the University of California, Santa Cruz, joins Ira to talk about the strategies game designers use to more deeply engage emotions such as empathy, complicity, and grief. But in the meantime, I wanted to see what the hype is about. Could Isbister recommend a few titles and tips for newbie gamers like me?

Welcome to the Emotion Arcade

As a non-gamer, one of my barriers to entry was always the expectation that I’d need to sink money into a gaming system. Not so. All the games Isbister recommends are available via the free gaming platform Steam (you will need to download Steam, however), and no individual game costs more than your average paperback. What’s more, none of the titles Isbister suggests are the gaming equivalent of a slow-to-start novel. They’re interesting—and complex—right from the get-go. “None of these games is a 50-hour type of commitment,” she says. And “here’s the dirty secret,” she adds. “A lot of experienced gamers, they watch playthroughs, and they look up FAQs when they get confused.” So if you’re new to a game, consider those Google and YouTube search bars your friend.

Her Story

Platform: Steam, iPhone or iPad

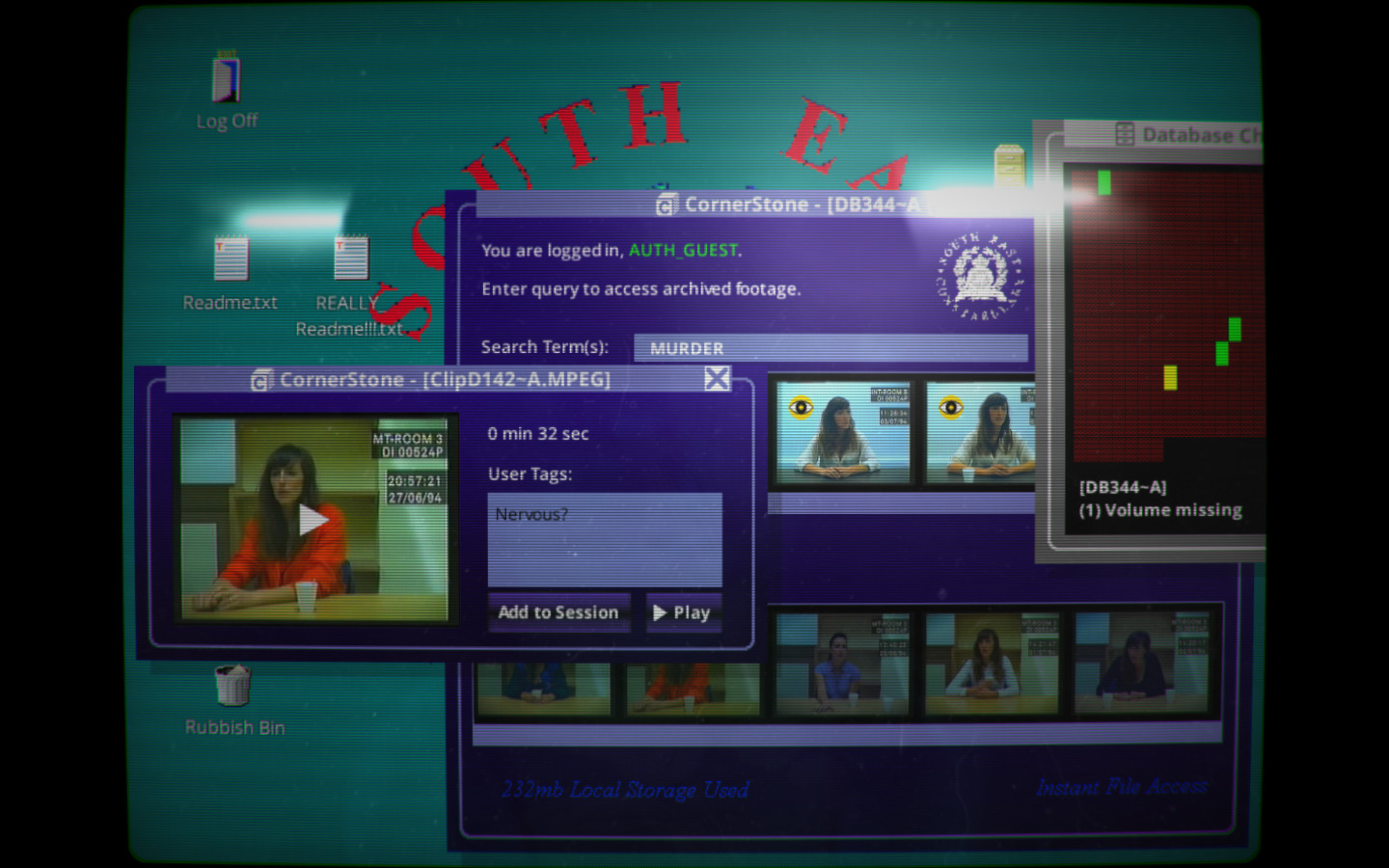

As Her Story boots up, I find myself peering at a late ‘90s computer belonging to the Portsmouth, U.K., constabulary. (Yes, I’m navigating a computer within my computer.) This blast from the pre-Y2K past is the interface for Her Story. Clicking around my “desktop,” I find hours of searchable videotape—interrogations with a mysterious woman whose husband, Simon, has been murdered. (A text file left on the desktop informs me that I’ve gained access to this circa-1999 police database through a Freedom of Information request.)

I don’t need to be told my objective in Her Story; it’s obvious. This is a whodunit. “You’re trying to sort out what’s happened to this woman who is being interrogated multiple times,” Isbister affirms, “[trying] to figure out what actually went down.”

I do this by querying the constabulary’s video database, using the names of other characters (“Simon,” “Diane”), locations (“Glasgow”), and plot points (“murder”) to dredge up additional tape. As details accumulate, I begin to wonder if I should be taking notes, like a real detective.

According to Isbister, the answer is yes. “There’s a really long tradition in gameplay of making notes and maps,” she explains. “That may be one reason that the average person isn’t always drawn to [certain] games.” Unraveling the mystery of Her Story takes real mental work—but it pays off. “There is definitely a major denouement regarding the interviewee,” Isbister says.

And then there’s the emotional workout the game provides. “I think this game is meant to get you to take a closer look, and try to really get in this other person’s shoes,” Isbister says. Without my fully realizing it, Her Story encourages me to empathize with—and scrutinize—the woman on screen. Because I’m watching an actual human being (albeit an actress) rather than an animated character, I have access to “rich non-verbal cues,” Isbister points out. I register the woman’s nervous smile, the worry in her voice, and the way she fiddles with her cup of tea. “[You’re] building some sort of connection to her, through the rich and emotive performance of the actress,” Isbister says. As for whether or not she’s guilty, you’ll probably have to break out the pen and paper to find out.

Papers, Please

Platform: Steam, iPad

For a medium that’s seemingly all about play, you might be surprised by the number of games that simulate work. Take Cart Life, a game where you can play the part of a bagel cart vendor. Or Disaffected!, a parody game that offers you the chance to be a discontented Kinko’s employee.

In Papers, Please, my job is similarly mundane. I am a border security officer employed by the fictional country of Arstotzka (seemingly a dystopian, communist, Soviet state). My task is to guard the Arstotzkan border, reviewing applicants’ passports, work permits, and fingerprint records to determine who gets in and who doesn’t. What’s surprising is just how enjoyable this turns out to be. I get into a groove (gamers might call it “flow”). I’m good at my job. And then things start to get complicated.

I allow a man to immigrate to Arstotzka. But his wife, who visits my checkpoint directly after her husband, doesn’t have her paperwork in order. Do I let her in? Later, I catch a man attempting to smuggle medicine through the border. He offers me a bribe. I know I could use the money. Do I take it?

Papers, Please prompts uncomfortable questions. Will I play in a subversive way? Will I play by the rules? “[The game] sets up this routine of being the worker, and then sets up these smaller and larger moral challenges or questions once you’ve got the gameplay down,” Isbister says. The border checkpoint is “a very clever premise to unlock emotion, because you are making the choices as each person comes through: Will I let them in or not?” What happens to your character (and to Arstotzka) depends on your answer.

That Dragon, Cancer

Platform: Steam, Ouya, Forge TV

Of the games I played, That Dragon, Cancer packed the hardest emotional punch—it follows a family struggling with how to care for their toddler son Joel, who has terminal cancer. The game is based on a true story. Joel’s father, Ryan Green, a game developer, created That Dragon, Cancer with his wife, Amy, and a team of designers. (You can hear Ryan and Amy Green talk about That Dragon, Cancer on SciFri on April 1.)

As a player, I follow Amy, Ryan, and their family as they experience the sometimes-mundane, sometimes-harrowing, sometimes-joyful moments that constitute caring for Joel. The actions I can take within a given scene are limited. For instance, I use my mouse to navigate the halls of a cancer ward, decorated with the tempera-paint handprints of tiny patients. I click once to send Joel gleefully down the slide at the playground. (He claps his hands and asks, “More?”). I hand him pieces of bread to throw to some ducks (which he gleefully does, laughing infectiously). And I urge him to sip from a juice box during a particularly hellish night at the hospital, hoping against hope that it might stop him from crying.

As Isbister sees it, the relatively limited range of actions available to players in That Dragon, Cancer is by design. “A lot of games, what they’re really about is making the player feel powerful and graceful and buoyant and light,” she explains. “This is a different feeling…You are kind of being trained to relinquish control at some level. And that’s a very intense emotional experience.”

You don’t “win” That Dragon, Cancer. You can’t change the outcome of Joel’s story. But that doesn’t mean your actions are futile. If That Dragon, Cancer has a strategy, Isbister says, it’s this: “You do what you can, and you enjoy the moments you have, and you focus on the short term view of optimizing,” she says. “You don’t have control over the narrative.” And you don’t have the luxury of a long-term story to work with.

There’s a lot more emotional territory to be explored through games beyond these three titles, according to Isbister. “One can find contemplative games, games of quiet joy, [and] games of heartfelt companionship,” she writes. And now that I’ve gotten my feet wet, I’m looking forward to trying them.

Game on.

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.