An Experimental Valley Fever Treatment Paves A New Path For Research

When four-year-old Abraham came to UCLA’s children’s hospital, his immune system couldn’t fight off his severe valley fever. Then, clinicians tried a new therapy.

This story by Kerry Klein was originally published KVPR Valley Public Radio. Listen to Klein in a Science Friday interview about valley fever and read a profile of patients and researchers in a multimedia feature on Methods, from Science Friday.

Hundreds of children and their families cycle in and out of UCLA’s Mattel Children’s Hospital each week, and yet Dr. Manish Butte still remembers the day almost two years ago when he met a young boy who could barely walk or talk and needed a feeding tube to eat.

“We saw these very large lumps on his forehead, and the lumps were full of fungal infection and they were burrowing through the bones of his skull,” Butte said.

Four-year-old Abraham Gonzalez-Martinez was suffering a life-threatening bout of valley fever, a disease caused by inhaling the spores of a fungus that lurks in arid soil in the American Southwest. Also known as coccidioidomycosis or cocci, the fungal disease typically infects the lungs but can spread into other organs, the bones and, in the most severe cases, the brain and nervous system.

“He was desperately ill,” Butte said. “He was on multiple antifungal medicines, top doses of everything, and the infection was still spreading.”

Listen and see valley fever patients and researchers in a special multimedia feature from Science Friday and KVPR Valley Public Radio on Methods.

Today, Abraham is back home with his family in Santa Maria, with his valley fever under control and his life largely back to normal. But that outcome didn’t always seem likely during his year-long stay in the hospital as doctors searched for a treatment that would return him to health.

Butte is a pediatric immunologist and a founder of the California Center for Rare Diseases at UCLA. The team takes on the hardest-to-solve cases, like those suffering from severe autoimmune diseases and rare genetic mutations, and pours all its energy into figuring them out.

In that way, Butte might resemble Dr. Gregory House, a TV doctor from the early 2000s who, despite a scathing grouchiness and penchant for Vicodin, saves a life in every episode by unraveling the most complicated medical puzzles. Butte, though affable with a candid smile and easy laugh, said he gets the comparison a lot.

“I hope I’m not as abusive and mean as Dr. House is,” he said, laughing. “But yes, in this clinic we only do mystery cases. So in that way, there’s a lot of parallels with the show.”

The young Abraham had originally visited a hospital near Santa Barbara, but the disease was so stubborn and fast-moving that doctors there sent him to the medical sleuths at UCLA. “We were going full-court press to try to save him,” Butte said.

Severe cocci isn’t unheard of, but Abraham didn’t fall into any groups known to be at elevated risk of the disease, like African Americans, Filipinos or pregnant women. As far as health officials knew, no one else had fallen ill in a local outbreak, and none of the child’s family members, who might have been exposed to the same conditions, seemed affected.

Confronted with these puzzling clues, some doctors may have simply diagnosed it as a case of tough luck, but Butte didn’t buy it. Perhaps there was a flaw in Abraham’s genes, or an error in his immune system.

To investigate, he brought in backup: Dr. Maria Garcia-Lloret, another pediatric immunologist at UCLA. “We always say that we don’t believe in bad luck,” said Garcia-Lloret, a fast-talking Argentine who’ll share her cell phone number with her patients.

She and Butte believe there’s always a reason the immune system breaks. “That’s the starting point is to be convinced that there’s got to be something here,” she said, “that bad luck is just a surrogate for lack of knowledge for exactly what’s going on in the immune system.”

Just maybe, they thought, if they could find that knowledge for Abraham, his case could help the thousands of others diagnosed with the disease every year. “Part of our job as scientists, as discoverers, is to try to peel that apart, understand what broke, and then understand how we can fix it,” Butte said.

For most people, valley fever passes with only mild symptoms or none at all. Sometimes it’s misdiagnosed as pneumonia or bronchitis. In rare cases, however, the disease can spread throughout the body. It kills a few hundred Americans and debilitates many more each year.

Why people respond so differently to the disease has puzzled experts for decades. Abraham’s case, and his intensive level of care, offer some insight into that question—and as more research funding trickles in, it may be the start of even bigger advances.

Butte, Garcia-Lloret and their colleagues dove into Abraham’s case not in his hospital room, but outside of his body, in the Butte Lab. Part clinic, part research space in a newly refurbished campus building, the lab has some of the most high-tech tools available anywhere: Flow cytometers to sort cells, atomic force microscopes to manipulate them, and liquid-nitrogen-chilled coolers to store blood and tissue samples.

Armed with these, the team counted, sorted and observed Abraham’s white blood cells, the front lines of the immune system. “We stimulate them and poke and prod them to make sure their function is working the way we think,” Butte said, “and then we sequence the genome to try to understand what genes there are and if they’re broken.”

The doctors didn’t find any genetic defects, so they zeroed in on the T cells, immune cells that fight off infection and disease. The immune system programs T cells into two main classes, each of which battles different families of threats. There, things got interesting: Abraham’s T cells had been programmed to fight the wrong threat, one that wasn’t even in his system.It resulted in an immune dysregulation that’s akin to sending a SWAT team into an empty building. “The rest of his immune system was telling his T cells, ‘Hey, we’re fighting a fungus today,’ and the T cells weren’t listening,” Butte said. “They were instead focused on fighting a parasite.”

Butte wondered: What if those T cells could be reprogrammed? And that’s when the team began building momentum. Garcia-Lloret, who specializes in allergic diseases, suggested Actimmune, a drug treatment for immune disorders that promotes the T cell Abraham needed. It worked—sort of.

“He was getting better. We were reasonably satisfied,” she said. But still, too many of Abraham’s cells were running the wrong program. “When we kept on looking at the lesions in the head and in the back, nothing was being fully resolved.”

By this time, Abraham had been in a hospital bed for months. Garcia-Lloret’s memory kept returning to an earlier case of a 17-year-old girl whose cocci had landed her in intensive care. “Slowly but surely, she ended up dying in the ICU,” Garcia-Lloret recalled. “I heard about that case 10 years ago or a little bit more, and it never left me.”

She couldn’t bear to let that happen to the four-year-old boy in front of her. She continued digging around and found another drug, a relatively new one named Dupixent that’s also meant to treat immune disorders.

As far as the doctors know, it had never before been used on valley fever. They tested it first in Abraham’s cells in the lab, then in his body, and bingo: “We saw that his skull bones were all healing, and you could see immediately that all the lumps of a fungal infection in his body were fading away,” Butte said.

Dupixent is just a few years old. It’s indicated for asthma and eczema, two disorders completely unrelated to fungal diseases, but it works by calming the part of the particular immune program that has gone haywire in Abraham’s system. Together, the drugs had simultaneously suppressed Abraham’s dysfunctional T cells and boosted those that could attack the fungus. Seeing them work together in Abraham’s body “turned out to be one of those eureka moments,” Butte said.

Within a few months, Abraham’s lumps and lesions had disappeared. He began eating and playing, and he talked more, singing along to YouTube videos and learning new languages. “Seeing him get better was a joy for all of us,” said Garcia-Lloret.

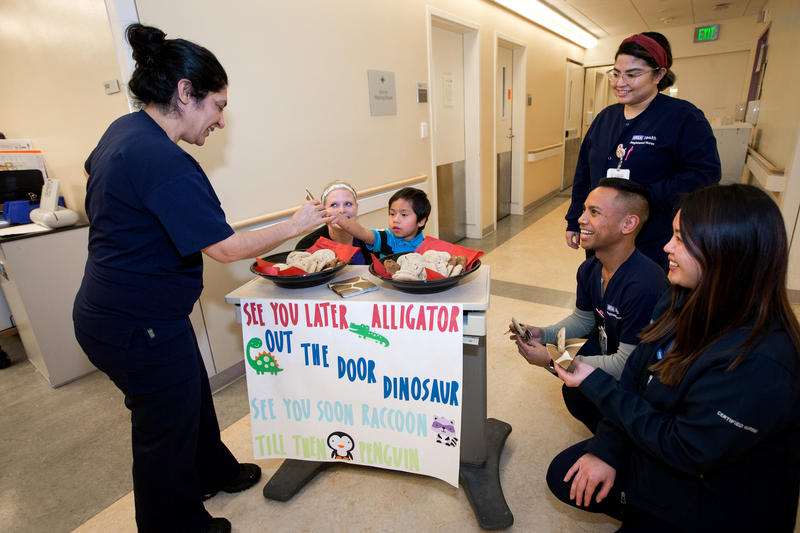

Finally, after 11 months in a hospital bed, he returned to his mother and older sister in Santa Maria in early 2019.

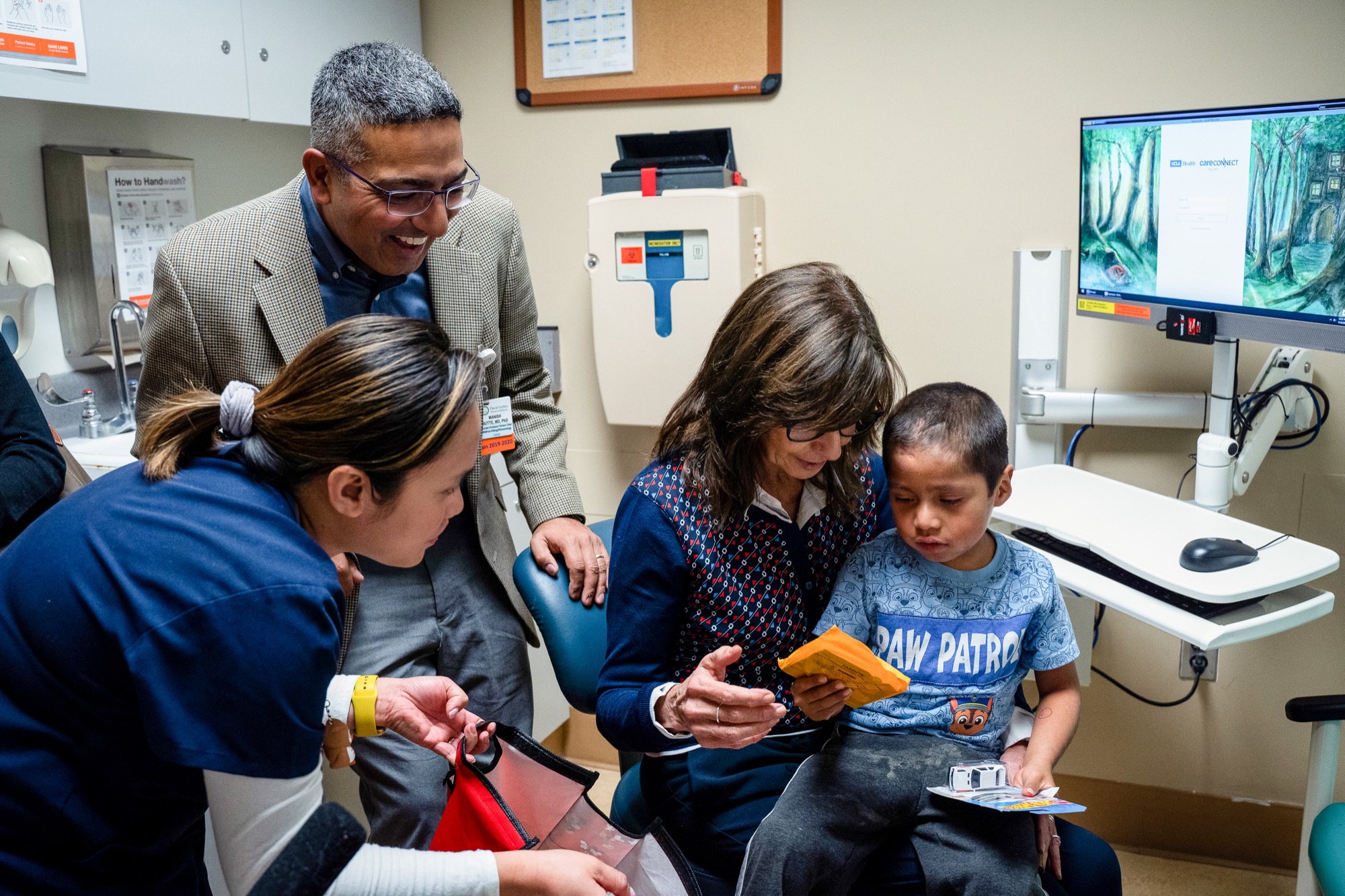

On a sunny November morning, nearly a year after he was discharged from the hospital, Abraham has returned to UCLA for a checkup. The now-six-year-old’s valley fever isn’t gone from his system, but it’s managed. His mother still injects him with a cocktail of drugs, and one goal today is to measure how his body responds to cocci this many months out. Despite weekly injections, Abraham still melts into panicked tears when a nurse approaches him with a needle.

A tiny boy in Batman socks and a Paw Patrol T-shirt, Abraham is smiley and sweet but painfully shy. During his stay in the hospital, he’d jump out at doctors from behind his curtains, and a video from his birthday shows him hopping from foot to foot while handing out cupcakes to staff. Today, however, pediatric dietitian Danielle Mein can barely get one word out of him at a time.

“What is your favorite food?” she asked. “Pizza,” he answered coyly, to which Mein agreed—pizza’s the best.

The fact Abraham is speaking English at all is a feat. He and his mother arrived at UCLA understanding only Mixteco, an indigenous language of Mexico. Throughout his 11 months in the hospital, however, he picked up bits and pieces of both English and Spanish.

“You know everybody at the hospital misses you?” Mein asked, to which he nodded. “But we’re glad you’re home,” she said.

During his stay, Abraham was practically raised by hospital staff. His mother, Magdalena Gonzalez, is a strawberry picker in Santa Maria. She was lucky if she could take just one day a week to travel the 300 miles roundtrip to visit him.

“Yes, it’s difficult,” said Gonzalez through an interpreter. “Sometimes I can’t find any transportation to come here.”

Gonzalez still isn’t comfortable in English, but the experience taught her enough Spanish to get by with bilingual staff. Garcia-Lloret, who developed a companionship with both Gonzalez and Abraham, said the petite, soft-spoken farmworker transformed right alongside her son, eventually managing his many prescriptions and fielding communication with both pharmacists and doctors.

All this, according to Garcia-Lloret, Gonzalez did without a driver’s license or being able to read or write in any language. “Having a patient like him with a chronic illness and so many medications is a challenge,” Garcia-Lloret said. “She’s gained my respect and my admiration.”

Abraham, meanwhile, seems blissfully unaware of just how ill he once was. He may also be unaware of how important he was to valley fever research.

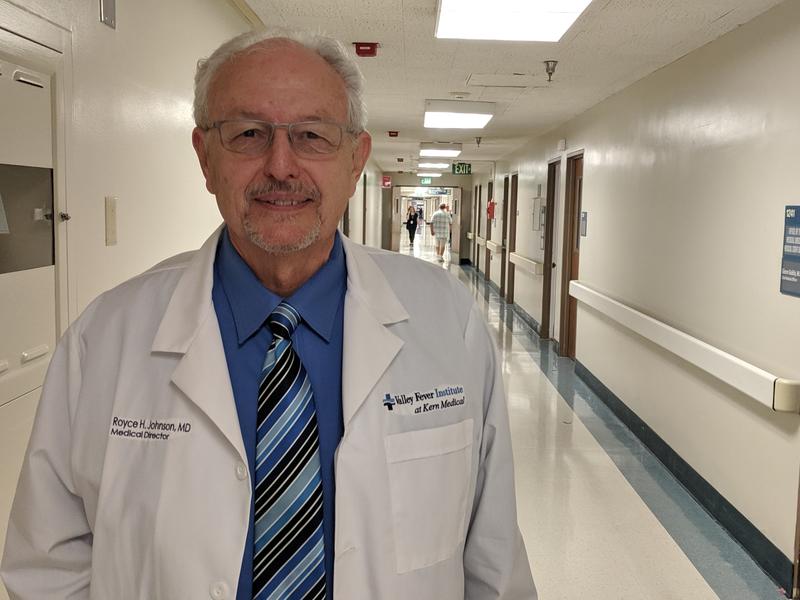

Abraham’s hospital experience falls into what’s called precision medicine, in which doctors use each patient’s unique circumstances and genetic code to develop a personalized treatment. For routine care, most patients don’t have access to so many resources. “It’s an unusual case for anywhere,” said Dr. Royce Johnson, a longtime cocci specialist and medical lead of the Valley Fever Institute at Kern Medical in Bakersfield.

He wasn’t involved in Abraham’s care but is familiar with the young boy’s case. “Very few patients unfortunately get the kind of extraordinary evaluation and care that this child received,” he said.

Having treated hundreds of patients with severe disease, Johnson has long been interested in why people exposed to the same spores can develop such radically different symptoms—and whether the answer could lurk somewhere in the body. In Abraham’s case, the key was in the immune system.

“I’ve wondered about this for years and years, but we didn’t have the technology to really try and answer the question until relatively recently with exome analysis, whole genome analysis,” Johnson said.

Could such resource-intensive care ever be within reach for the thousands of people diagnosed with the disease each year? Yes, believes Johnson, someday.

Dr. Paul Krogstad, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at UCLA, agrees. With decades of valley fever experience behind him, he treated Abraham alongside Butte and Garcia-Lloret.

Krogstad says Abraham was a test case, and later patients should only become easier to treat. “If you improve the science so that you can figure out what the needs are, you often can reduce the amount of the complexity of care that’s required,” he said—and the cost.

To that end, these researchers and others across three University of California campuses and the Valley Fever Institute have launched a new project to study the immune systems of 50 valley fever patients in nearly as much detail as they studied Abraham’s.

Among other goals, Krogstad said, they hope to find additional examples of immune dysregulation “to help a person recover and have a shorter course of valley fever by helping intensify the immune system by refocusing it.” Someday, researchers may even find a way to predict early on whether a patient is likely to develop severe disease.

The project was partially inspired by Abraham, though it had been in the works well before he appeared at UCLA, and it’s made possible by state funding allocated by former Gov. Jerry Brown. After decades of slow research progress, Krogstad said it’s refreshing to see rising interest in the disease.

“We simply haven’t seen sufficient attention paid to this condition,” he said. “I’m afraid it has just looked like a regional problem that didn’t require special attention.”

Abraham’s case also caught the eye of big pharma. Horizon Therapeutics and Sanofi, the manufacturers that produced the immune drugs that saved Abraham’s life, confirmed that they’ve been talking with UCLA about further research and, potentially, clinical trials on more valley fever patients.

As for Abraham himself, his doctors plan to start weaning him off his many drugs in the coming months. They hope someday he’ll be done with them for good. One can imagine the kindergartner himself also wants to be rid of needles, so that maybe he can just focus on normal kid concerns: his favorite animals (flamingoes), his favorite color (red) and, of course, pizza.

Read and listen to the story on KVPR Valley Public Radio. The story is a part of the series “Just One Breath” by the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative. Learn more about valley fever in our feature on Methods, from Science Friday.

Kerry Klein is a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California.