This Tiny Seahorse Has Mastered Its Domain

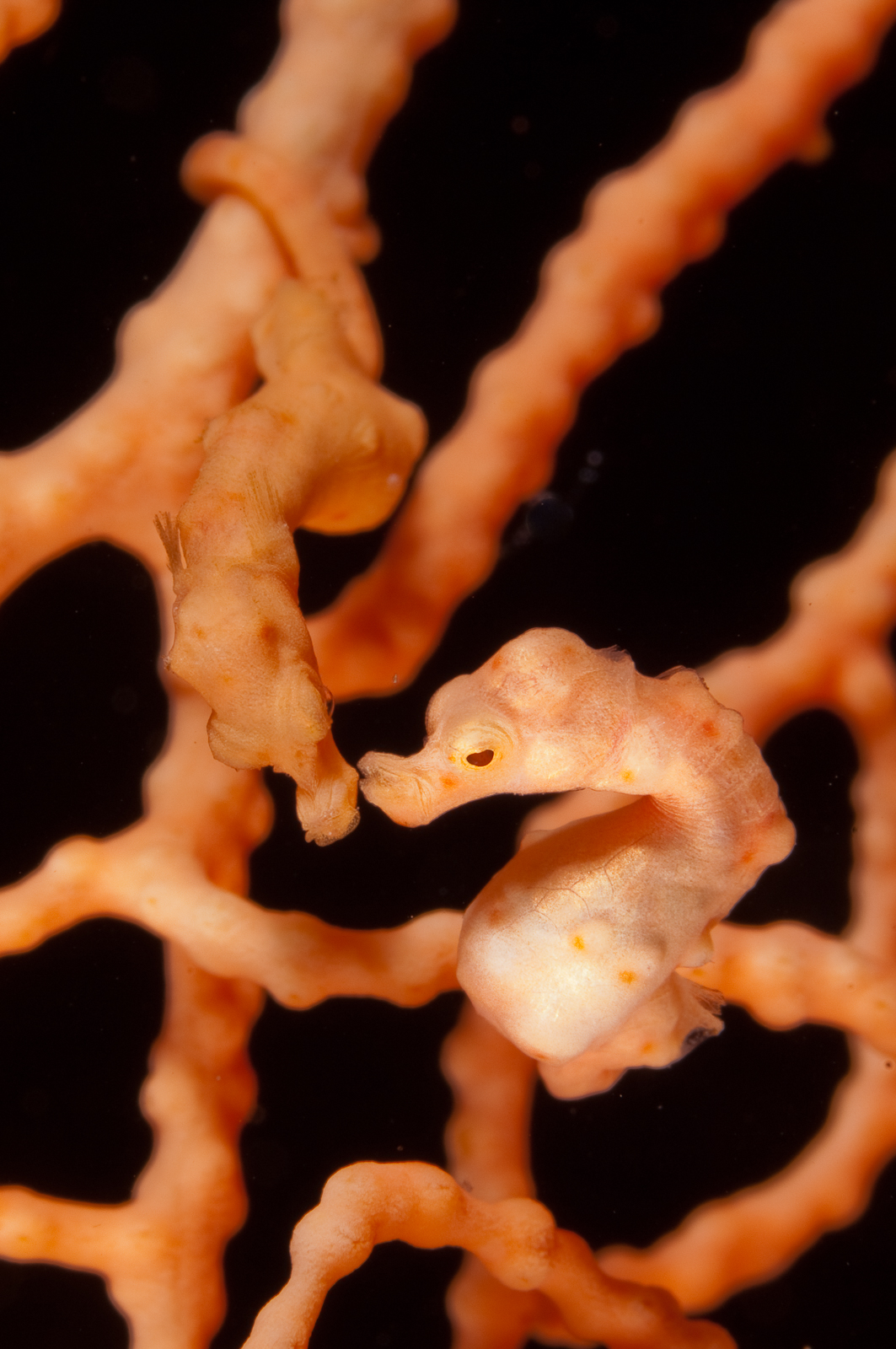

To hide in the knobby sea fans they call home, Bargibant’s pygmy seahorses have evolved exquisite camouflage.

In August 1999, conservation biologist Sara Lourie and underwater photographer Denise Tackett were diving off the coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia, researching a tiny seahorse species called Hippocampus bargibanti, when they witnessed an epiphany: a male giving birth. Over the course of 15 minutes or so, 34 miniscule babies—each about two millimeters long—popped out of their father’s belly as Lourie and Tackett watched, mesmerized.

“As far as I know, that was the first time anyone had ever seen [H. bargibanti] pygmy seahorses giving birth, and we certainly had no idea that they would have so many babies,” recalls Lourie, a research associate at the conservation organization Project Seahorse and author of the recent book Seahorses: A Life-Size Guide to Every Species.

[Climate change is washing away graves in the South Pacific.]

Hippocampus bargibanti was the first described species of pygmy seahorse, a reference to its diminutive size. Also known as Bargibant’s pygmy seahorses, (for their discoverer, a scientist named Georges Bargibant), they reach nearly 30 millimeters when fully grown—just a bit longer than the diameter of a U.S. quarter, according to underwater photographer Richard Smith, who researched this species and a close relative, Hippocampus denise, for his doctoral thesis.

As a tropical Pacific seahorse, H. bargibanti generally dwells in the “Coral Triangle,” a marine region encompassing Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands, although in 2015, Smith recorded the first sighting in waters around Japan, near Tokyo.

Bargibant’s pygmy seahorses are known for their clownish camouflage, which generally entails a full-body array of reddish-pink or orangey-yellow calcified bumps, called tubercles. Their marine attire exquisitely matches the knobby sea fans—members of a group called gorgonians—on which they depend for food and shelter. Specifically, H. bargibanti nestles amid the branches of Muricella gorgonians, according to Smith, the founder of Ocean Realm Images and a dive expedition leader. “It’s a real habitat specialist,” he says.

[Did you know that sea spray can change the weather?]

Bargibant’s seahorses aren’t unique for bucking gender norms—all male seahorses rear their young. But unlike many other species, H. bargibanti and its pygmy relatives (there are about a handful of species) carry the eggs in their belly rather than in a pouch at the base of their tail. “These are just adaptations, basically, because [pygmies are] so tiny,” says Smith. “If they had the brood pouch on the tail, then they would probably have difficulty with holding onto anything.”

Of the various seahorse species studied, most are known for forming partnerships called pair bonds, which they tend to reinforce through a “daily greeting”—it’s tempting to interpret it as cuddling—during which they might entwine their tails and twirl, or shake and sway next to each other, while brightening in color. Bargibant’s pygmy seahorses probably engage in such greetings, according to Smith, based on research he’s done on H. denise.

When it comes time to mate, seahorses that engage in daily greetings generally extend that ritual into a more elaborate display that ultimately says, “I’m ready!” A few years ago, biologists at the Steinhart Aquarium, part of the California Academy of Sciences, raised H. bargibanti in captivity for 126 days, and observed the species in mating mode. The interaction appears to go something like this: A male and female first trail each other around the sea fan, getting closer and closer until they’re facing one another. “By some signal, they decide, ‘this is when it’s gonna happen,’” says Richard Ross, a senior biologist at the aquarium. The pair then levitates from the safety of their fan, tails intertlaced, and the female deposits her eggs in about 30 seconds. They descend after that, but may repeat the process once or twice.

The males are pregnant for about two weeks, after which they’re ready to go at it again. “He gives birth, and then half an hour later, he’s mating again,” says Smith. Judging from the pygmies he’s studied, H. bargibanti probably only lives about a year, so “basically their whole thing is just producing as many offspring as they can,” he says. When the fry emerge, they’re essentially miniaturized adults that immediately bid a seahorse sayonara, drifting off to eventually find a gorgonian home of their own.

During that memorable dive off Sulawesi, Lourie and Tackett stayed underwater longer than they had intended, just to watch the H. bargibanti babies disperse. “We didn’t want to miss this amazing event,” says Lourie.

Julie Leibach is a freelance science journalist and the former managing editor of online content for Science Friday.