This ’70s Artist Painted Our Future In Space

Forty years ago, artist Rick Guidice teamed up with NASA scientists to envision the space civilizations of the future.

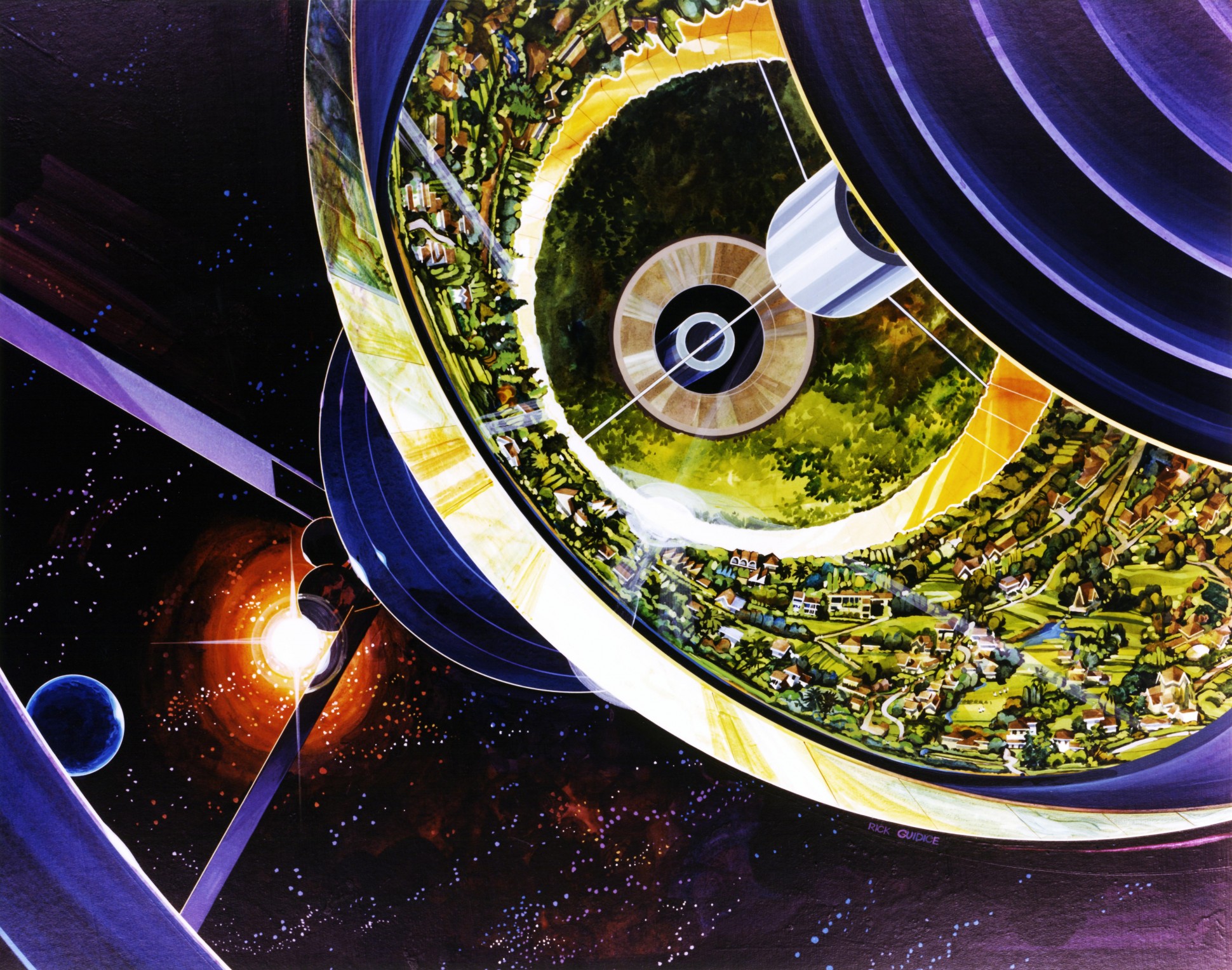

"Cutaway of Bernal Sphere Habitat," by Rick Guidice, 1976. This colony is comprised of two large spheres. The interior sphere rotates twice per minute to create gravity similar to that on Earth, while the outer shell shields space colonists from cosmic rays. Image courtesy of NASA Ames Research Center and New Museum Los Gatos.

Before computer-illustrating software, aerospace engineers and astronomers turned to the skillful hands of technical illustrators to depict future space missions. Los Gatos-based artist Rick Guidice was among them. In 1971, he went from drawing earthbound buildings at an architectural design firm to painting celestial bodies and space settlements for NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California.

Guidice was born and raised in San Jose, California, not far from the tech start-up companies sprouting across Silicon Valley. He began doing architectural illustrations when he was just 16-years-old, later studying fine art at the Academy of Art College in San Francisco. Between stints illustrating game advertisements for Atari and military maneuvers for the United States Air Force, Guidice worked for more than a decade alongside NASA scientists, illustrating missions and research so that their work could be shared with the public.

Sometimes that meant filling in the details of a picture when the science was still developing. For example, Guidice remembers receiving fuzzy photos of Jupiter and Saturn—the source material available at the time—and being asked to paint NASA’s Pioneer probes zooming past the planets. “I drew paintings of these missions and what these planets would possibly look like without them being seen before,” he says.

Now a selection of Guidice’s work is on display at New Museum Los Gatos in California. The exhibit, which runs through February 14, 2016, focuses on his depictions of space settlements.

In the 1970s, NASA was building up the space shuttle program to send humans beyond Earth’s atmosphere. That got some researchers thinking big about what could come next, such as structures capable of supporting whole cities and civilizations in space. During the summers of 1975-1977, scientists gathered at NASA Ames and Stanford University to design space settlements that incorporated only existing technology. The researchers asked how people would grow food, generate energy, and build colony infrastructures in outer space.

“The scientists wanted to know what would it be like if this earth became uninhabitable, and we had to turn to space,” says April Gage, an archivist working at NASA Ames. “What would it look like?”

It was Guidice’s job to illustrate several space colony concepts discussed in the Stanford sessions, including the O’Neill Double Cylinder (1975), the Bernal Sphere (1976), and the Stanford Torus Wheel (1976). While some colonies were intended to accommodate about 10,000 to 20,000 people, the O’Neill Double Cylinder could house on the order of a million, and was designed to generate its own gravitational pull, as well as simulate weather patterns found on Earth.

“If you think about the International Space Station, maybe four to five people are on that station,” says Gage. “When you look at these colonies, they are about 100 times larger. [The researchers] were looking at this using the technology of 1975. It’s fascinating to think about.”

While Guidice had no formal science training, he attended meetings with NASA’s mission directors and scientists to make sure he accurately reflected the technology discussed in the sessions. His depictions of gargantuan, space-roaming colonies might resemble the CGI-generated machines and hovercrafts seen in today’s science fiction movies. But back then, everything had to be done by hand, he says. “It was just drawn on paper with pencil [and paint], but it was done a long time ago in a very romantic fashion, you might say.” Each painting took him about three weeks to complete.

Guidice liked to paint with acrylics and often used warm, bold colors to give a luster to gases and stars. When Marianne McGrath, the curator of the space settlement exhibit at New Museum Los Gatos, came across his paintings, she was struck by how he transformed the science behind the designs into beautiful visions. “It’s not so cold or dark or vast,” she says. “The stars are almost within reach in these paintings.”

The three different colonies don’t appear as tin cans floating in outer space, but as a second home where people would want to live, McGrath says.

None of these settlements were ever constructed, but the colony concept lives on in NASA Ames’ annual Space Settlement Contest, which asks students up to 18-years-old from around the world to design their own space colonies. Recent research papers have also proposed scaled-down iterations of these colonies, residing within Earth’s orbit.

When Guidice’s paintings were first revealed to the public in the late 1970s, many people were surprised by how similar living in space seemed to how we live on Earth. That was by design, says Guidice. This portrayal of space colony life “is pleasurable to look at,” he says. What’s more, “it’s still something that looks into the future. When you look at it today, you get the same feeling and reaction of possibility as we did back then.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.Donate To Science Friday

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.