The ‘Rebellious Scientist’ Who Inspired Kurt Vonnegut

The story behind the Kurt Vonnegut story about an antiwar scientist named Professor Barnhouse.

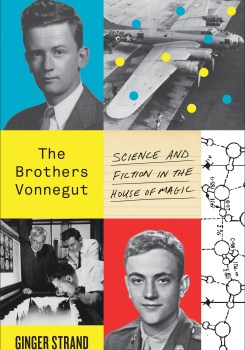

The following is an excerpt from The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic, by Ginger Strand.

Kurt was thinking about what might happen if a scientist refused to tell the military men what they wanted to know. A scientist had recently done just that: Norbert Wiener.

Professor Norbert Wiener of MIT was one of the world’s leading mathematicians. He was good friends with John von Neumann, but the two men could hardly have been more different. In January 1947, Wiener had made national news by canceling a talk at an MIT symposium on high-speed calculating machines because the conference was funded by the military. Just before the conference, The Atlantic had published Wiener’s open letter to an aircraft company researcher who requested a copy of a paper on controlled missiles Wiener had written during the war. Wiener refused to give it to him. It was simple, Wiener wrote. He had done that work under government contract because he thought he should assist the war effort. But then he had seen the results.

“The policy of the government itself during and after the war, say in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” he wrote, “has made it clear that to provide scientific information is not a necessarily innocent act, and may entail the gravest consequences. One therefore cannot escape reconsidering the established custom of the scientist to give information to every person who may inquire of him.” Scientists had now become arbiters of life and death, he declared, and he was censoring himself because “to disseminate information about a weapon in the present state of our civilization is to make it practically certain that that weapon will be used.”

Wiener’s letter had made a big impression in Schenectady. The scientists Kurt knew at GE often discussed issues like those he raised. Had it been morally right to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima—and on Nagasaki? If morally wrong, were the scientists who built the bomb as guilty as the generals who decided to use it? Wiener’s vow of noncompliance was admired by many in the Scientists’ Movement and beyond, but it was disturbing too. Should scientists censor themselves? Didn’t knowledge belong to the world at large?

Two years of debate had not settled the question. In November 1948, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists had published Wiener’s follow-up essay, “A Rebellious Scientist After Two Years.” Again, Wiener pulled no punches. “The degradation of the position of the scientist as an independent worker and thinker to that of a morally irresponsible stooge in a science factory has proceeded even more rapidly and devastatingly than I had expected,” he wrote. “In view of this, I still see no reason to turn over to any person, whether he be an army officer or the kept scientist of a great corporation, any results which I obtain if I think they are not going to be used for the best interests of science and of humanity.”

A morally irresponsible stooge in a science factory! Some people might look at the GE Research Lab and see exactly that. GE made no effort to hide its cozy relationship with the military; on the contrary, it boasted of it. But what did this mean for scientists like Bernie? Were they really kept scientists, ethically deficient worker ants mindlessly contributing to a proliferating war machine? Kurt knew his brother was at heart a pacifist; their parents had raised them that way, and the war had only deepened the conviction for them both. But as soon as cloud seeding was made public, its military uses were being discussed. There was General Kenney telling the graduates of MIT, “The nation that first learns to plot the paths of air masses accurately and learns to control the time and place of precipitation will dominate the globe.” That made Bernard uncomfortable. But because of his discovery, he was now answering to the generals. If a scientist like Bernard wanted to stop his work from being used for violent ends, what might he have to do?

Kurt’s new story was different from anything else he had written. There was no grieving widow or office romance, none of the crowdpleasing claptrap he had been churning out, hoping to please the slicks. Nor was there mention of World War II. Instead, right there at his desk in the Schenectady Works, from his vantage point in GE’s science factory, he began to imagine an antiwar scientist named Professor Barnhouse.

Professor Barnhouse discovers something shocking: he has the ability to control things previously thought to be uncontrollable. But his dream of using his power for humanity’s benefit soon crumbles as he realizes that the military men only see its value as a superweapon.

He called the story “Wishing Will Make It So: A Comprehensive Report on the Barnhouse Effect.” On one of the first full drafts, he crossed out “Barnhouse.” Was it too close to his brother’s nickname, Barney? He made the professor Brenhaltz instead. Lots of scientists had German names. Before long, he restored it to Barnhouse.

The story is narrated by Barnhouse’s student because the professor himself has disappeared. Barnhouse’s student has been tasked with explaining the history of the “Barnhouse effect.” It began, he explains, when Barnhouse, an artillery private in the Army, rolled sevens in his first barracks dice game—ten times in a row. Like Langmuir with his New Mexico storm, Barnhouse went off and excitedly calculated the odds of that happening by chance: they were one in sixty million. He tried rolling dice again and realized he could produce the effect: he had telekinetic powers. He began consciously cultivating this power, “dynamopsychism,” until eventually he could destroy entire buildings from miles away.

Barnhouse keeps his power secret at first, annoying the student-narrator with what seem like irrelevant questions. His favorites are “Think we should have dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima?” and “Think every new piece of scientific information is a good thing for humanity?” He reveals his power to his student-narrator when he decides to declare it publicly, in a letter to the secretary of state.

“I have discovered a new force which costs nothing to use,” he writes, “and which is probably more important than atomic energy.” It was exactly the same claim Langmuir was making about weather modification. And like Langmuir, Professor Barnhouse quickly finds himself taken up by the military. A Senator Warren Foust—sounding a lot like General Kenney on the topic of weather control—declares, “He who rules the Barnhouse Effect rules the world!” The military starts a dynamopsychism program, naming it “Project Wishing Well.” It secludes the professor and his student in a safe house under the protection of guards on loan from the Atomic Energy Commission and plans a secret test of the Barnhouse effect called “Operation Brainstorm.” It succeeds brilliantly. Barnhouse, sitting on a couch, uses his dynamopsychic powers to destroy ten V-2 rockets fired in New Mexico, bring down fifty radio-controlled bombers over the Aleutians, and completely disarm 120 target ships headed for the Caroline Islands. The generals are so elated by the operation’s success they don’t notice when Barnhouse slips away. It’s left to the student to read aloud the manifesto the professor has left behind.

The manifesto opens with the kind of pun Vonnegut could never resist. “Gentlemen,” the professor writes, “As the first superweapon with a conscience, I am removing myself from your national defense stockpile. Setting a new precedent in the behavior of ordnance, I have humane reasons for going off.”

The manifesto goes on for another page and a half. The tone is Norbert Wiener’s, but the politics are even more overt. In fact, the manifesto could have come directly from a United World Federalists position paper. Barnhouse points out the fallacy of trying to forge peace by building weapons and declares that the world cannot afford a nuclear war. He chastises the generals for failing to put their faith in government—in particular, the downtrodden United Nations. He explains that henceforth he will be making sure UN recommendations are carried out. And he demands that there be no more vetoes—just as the Scientists’ Movement had insisted a few years earlier. The story ends with the professor noting that if the world leaders don’t like it, they can lump it; he’s in control now.

Even as it addressed the vexing ethical quandaries raised by science, “Report on the Barnhouse Effect” was an optimistic story. The professor is a good person, an idealist with the power to enforce his principles. He sets an example for scientists much as Norbert Wiener did: he refuses to cooperate with the war machine. If enough scientists like Barnhouse would just step forward, the madness of an arms race could be averted.

Professor Barnhouse was the first in a long line of fictional scientists Kurt Vonnegut would write into being. He was also the most unambiguously noble, born at one of the last moments when Kurt thought that politics might still turn around, that the world might come to its senses and find its way to a new, enlightened era of prosperity and peace.

Excerpted from The Brothers Vonnegut by Ginger Strand, published in November 2015 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Ginger Strand.

Ginger Strand is the author of The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015). She’s based in New York, New York.