The Problem With The Plasma

In this excerpt from “Nine Pints,” Rose George explains how issues with the 1970s American plasma led to a contaminated supply.

The following is an excerpt of Nine Pints by Rose George.

Julian Miller sits on a chair in a TV studio. Its color scheme is 1980s beige but he is not. He wears a loud checked jacket, a pink shirt, and glasses that are the size that glasses were in the 1980s, so half his face is lenses. He has blond hair and eyes so blue, as serene and charming as his upper-class accent. He is probably the first hemophiliac to go on television and say he is HIV-positive.

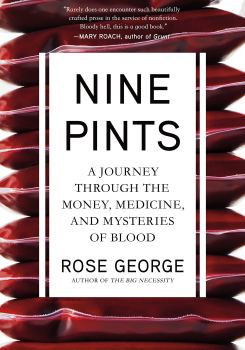

Nine Pints: A Journey Through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood

He thought he had been infected in the early 1980s. He was told after a routine blood test in 1984. His manner on TV is astonishingly calm. He smiles now and then, when he calls himself a “spontaneous mutation,” because he was the first hemophiliac in his family. He speaks of horrific things with the modulated serenity of priest or counselor. “In 1979,” he says, “it began to be fairly plain that there might be a problem with AIDS infection of American blood products.” He took himself to the venereal diseases clinic at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, as that was the only place then to get information on this new disease called AIDS. He sat down in the corridor “with all the other people who were waiting to see him for a different reason”—another grin— then saw a consultant. “He told me in a very grave, serious way about AIDS [. . .] and I left rather shocked.” His own hemophilia doctor, when Julian expressed his concern, gave the advice that most other worried hemophiliacs were given at the time. Carry on as normal. He said, “‘You’re in more danger of a life-threatening bleeding episode than you are of getting AIDS.’ So I carried on and in October 1984, having been tested, they told me I was HIV-positive.”

Ade Goodyear was fifteen when he was told he was HIV-positive. At Treloar [an English boarding school for disable children], Goodyear told the BBC, “we went into the office in the medical center in groups of five.” The atmosphere was relaxed but weird, because they had heard rumors. All schools have rumors, but not usually the kind that might kill you. “The doctors cautiously informed us that ‘you may have heard that Factor VIII [a therapy commonly used by hemophiliacs at the time] is not as clean as it should be.’” Then, with artless horror, “we were told who had HIV by the words ‘you haven’t, you have, you have, you haven’t,’ and so on.” The boys asked how long they had got. Two years. Maybe. Of those five boys in that room, Goodyear is the only survivor.

The trouble for Julian, and for thousands of other hemophiliacs who injected hepatitis and HIV with their Factor, is who their donors were, what they were donating, and how Factor was manufactured.

By the mid-1970s, the UK’s plasma supply had problems. Concentrates were too popular, and the country could not find enough plasma to process. Most countries aim for self-sufficiency in their blood and plasma supply, but plasma concentrates require a level of donations that hardly any country can maintain. In 1973, the UK began to import Factor from the United States. Many other countries did the same. The United States, in the 1970s, was supplying half of Europe’s plasma. In his book Blood, Douglas Starr quotes Tom Drees, then president of the Alpha Therapeutic Corporation. “‘As the US feeds the world,’ Drees told a conference of fractionators, ‘so does the US bleed for the world. Or, more correctly, the US plasmaphareses itself for the rest of the world.’” How? Because they paid people for it. Sometimes, the kind of people you want nowhere near a safe blood supply.

How do you make blood safe? According to the World Health Organization, you take it from volunteer donors who are not paid and who have no reason to lie about their health. Plenty of studies show that when donors are paid, they are more likely to lie about it. Obviously they do: they want to keep getting paid. Paid donors are also more likely to come from sections of society that have poor health to begin with. But the US blood supply has always rested on commerce and transaction. After the Second World War, countries such as the UK, France, and the Netherlands developed a non-remunerated blood supply, often run by a single government entity. The United States did not. It took a book by a British sociologist to change the world. (That is not a sentence you will read often.) In 1970, Richard Titmuss published The Gift Relationship, and it threw the blood business up in the air. He compared the UK’s voluntary, altruistic system with the fee-paying blood business in the United States, and his conclusion was damning for those who considered blood to be a product to be bought and sold like any other. Paying for blood made it unsafe. He wrote soberly, but he used words like “moral” and “right.” Even so, it was only in 1978 that the FDA required all blood to be labeled as paid or voluntary donation, and payment for blood died out.

But payment for plasma did not. Somehow, plasma taken from blood has become something other than blood: tamer, and less biological. Something you can pay for. This parallel reality began during the Second World War, when a doctor, Edwin Cohn, developed plasma fractionation for military use (plasma derivatives were easier to transport). In the 1950s, trials with gamma globulin, a protein isolated from plasma, proved successful at treating polio. Companies realized how successful plasma might be, if transformed into pharmaceutical products. Trade data lump whole blood and plasma together under the same category but in practice the United States treats them differently. Environmental activists talk of greenwashing: perhaps this was yellow washing. Anyway, it worked. Blood and plasma grew apart in concept and regulation. Now donors gave blood and sellers sold plasma.

But the plasma had to come from somewhere, and lots of it. Even paying for plasma did not bring in the huge numbers required to make good business. What about getting it from a captive resource? In 1947, German doctors were put on trial at Nuremberg for perpetrating “ghastly” and hideous experiments on concentration camp prisoners. Part of their defense was that Americans were also guilty of it. Some prisoners had been infected with bubonic plague in the name of science. Before the war, a doctor named Leo Stanley transplanted testicles from executed prisoners to “senile and devitalized men.” Later he switched to animals, injecting several hundred San Quentin residents with “animal testicular substance” from goats, rams, and boars. During the war prisoners took part in experiments that exposed them to gonorrhea, malaria, and the induction of gas gangrene. Sixty-two Sing Sing inmates volunteered in 1953 to have themselves injected with syphilis. Nearly half developed the disease, which attacks the eyes, brain, heart, liver, bones, and joints, and which can kill. In return, they got “a carton of cigarettes brought in by the doctors at Christmas time, a brief note on their records, and the good feeling which comes from having done something to help others.”

During the war, more than seventy thousand American inmates gave blood to the Prisoners’ Blood Bank for Defense. For the next two decades, there were enterprising efforts to rehabilitate or coerce or coax prisoners into better behavior by using their blood. In the 1950s, writes Susan E. Lederer in Flesh and Blood, “prisoners in the Virginia State penitentiary received days off their sentence for each pint of blood donated.” Prisons in Massachusetts, South Carolina, Mississippi, and Virginia offered prisoners five days off their sentence for each pint of blood given. Prisoners were used to giving up body fluids for profit; they would be a rich pool for plasma.

Read about the activities of the plasma industry and you will perhaps wonder why they were never turned into a James Bond film. Companies such as Baxter, Grifols, and Octapharma, which control the industry and which are vast conglomerates with secretive billionaire bosses (in the case of Octapharma), set up clinics in skid rows and prisons all over the country. They also harvested plasma from poor countries. As Douglas Starr writes in Blood, the Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza had shares in Plasmafaresis, a plasma harvesting company in Nicaragua, which sold plasma to the United States. Locals called the facility “the house of vampires.” In Haiti, a company named Hemo Caribbean paid vendors $3 a sale—$5 if they accepted to have a series of tetanus shots—and flew it out on Air Haiti to buyers in the United States and Europe. New York Times reporter Richard Severo, who exposed the unpleasant trade in poor people’s plasma, wrote in 1972 that the company was shipping 6,000 liters a month, and looking to expand. Haitian sellers had the motivation of being desperately poor. They also had one of the lowest caloric intakes in Latin America, as well as alarming rates of tuberculosis, tetanus, gastrointestinal diseases, and malnutrition. Hemo Caribbean’s technical director, a Mr. Thill, said that “few if any diseased persons slip through,” and even if they did, even if they had venereal diseases or malaria, he was confident that the freezing process killed such bacteria. In Cummins Jail in Grady, Arkansas, seventy miles south of Little Rock, a plasma center had been running since 1963. Prisoners were given $7 in exchange, and the plasma was sold for $100 a donation. They queued up in the center to lie down on cots and sell. They were “like little cows,” said an official who worked with Bill Clinton, twice governor of Arkansas. The little cows were milked and business was good. In 1974, the prison began selling to a company called Health Management Associates. HMA sold the plasma to North American Biologics, a subsidiary of Continental Pharma Cryosan, a Canadian company. (Cryosan later pleaded guilty to “mislabeling” blood from Russian cadavers as coming from Swedish donors. We’ve all done that.) From there, prison plasma was exported worldwide, to Canada, France, Iran, Iraq, Japan, the UK, Hong Kong.

Titmuss’s book caused upheaval in the blood business but not the plasma business. Yet in 1975 a California surgeon named J. Garrott Allen wrote to the Blood Products Laboratory in England, which had been buying American plasma products for years. Did they know, he inquired, that American plasma was “extraordinarily hazardous” and taken 100 percent from “Skid Row derelicts”? It also contained worrying levels of a new variety of unknown hepatitis, later called non-A, non-B, and finally C, which was more frequently encountered in “the lower socioeconomic groups of paid and prison donors.” The practice of selling blood became so popular with some socioeconomic groups, the press began to call it “ooze for booze.” Allen’s research showed that rates of hepatitis in prisoners and skid row donors were ten times higher than in the general population. Drug use, needle sharing, general poor health: all of these were risk factors. But nothing changed. Prisoners and the poor were too good a resource.

Reporters embedded themselves on skid row and wrote firsthand accounts. In 1975, reporters for World in Action, a British investigative current affairs TV program, traveled to various US cities to meet people who were selling their plasma. A man named Gary in San Francisco was asked whether he always answers questions about his health truthfully. “No.” He reconsidered. “You know, yeah, most of the time.” He is scornful of the health screening. “I’m healthy, you know?” Another donor says simply, “Pardon me while I puke.”

By 1980 in the US, payment for blood had come to be seen as unethical. But 70 percent of the country’s plasma came from paid sellers and no one saw anything wrong with it. BPL did not act upon Dr. Allen’s warnings. Hemophiliacs had no intention of giving up Factor and going back to endless hospital stays. They wanted it for three reasons: It gave them a life. They didn’t know about hepatitis C. And no one had told them about HIV, insidiously making its way to being a global pandemic.

Excerpted from Nine Pints by Rose George, with permission from Metropolitan Books Henry Holt and Company. Copyright 2018 © by Rose George.

Rose George is a journalist and author of Nine Pints: A Journey Through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood (Metropolitan Books, 2018). She’s based in Leeds, England.