The Origin Of The Word ‘Umami’

There’s science behind deliciousness.

Find out how umami redeemed MSG’s reputation. Listen to this episode on the new Science Diction podcast!

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

From the Japanese word for “deliciousness.” But the story of how the “fifth taste” entered our lexicon is equal parts science and cultural history.

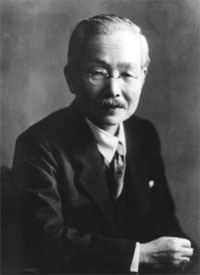

Early in the 20th century, a Japanese chemist named Kikunae Ikeda was puzzled by a certain dashi broth. The broth contained no meat—kombu, or kelp, is a key ingredient in dashi stock—yet it had a sumptuous, layered, and deeply satisfying flavor, akin to a long-simmered stew. Suspecting that there was something else at play beyond the accepted four basic taste sensations of sweet, salty, sour, and bitter, Ikeda decided to investigate the seaweed’s chemical composition.

After chemically treating the seaweed using a number of methods including removing the mannitol, sodium choloride, and potassium chloride, small crystals formed on the kombu. The crystals were chemically identical to glutamic acid, which is a type of amino acid found naturally in the human body. When the crystals were dissolved in liquid or sprinkled on food, the flavor exploded. Ikeda coined this sensation—which has been heralded as the “fifth taste”—umami, or “deliciousness.”

[What will restoration look like after the CA wildfires?]

Over the past few decades, umami has exploded in both cultural and scientific popularity. Articles about umami recipe competitions appear in the New Yorker, and hits for “umami” in PubMed (a database for medical literature) increased tenfold in less than two decades. (In 2000, there were 86 hits for studies that used the term or were archived under “umami.” Last year, there were over 800.) But it was a long, simmering process to get there.

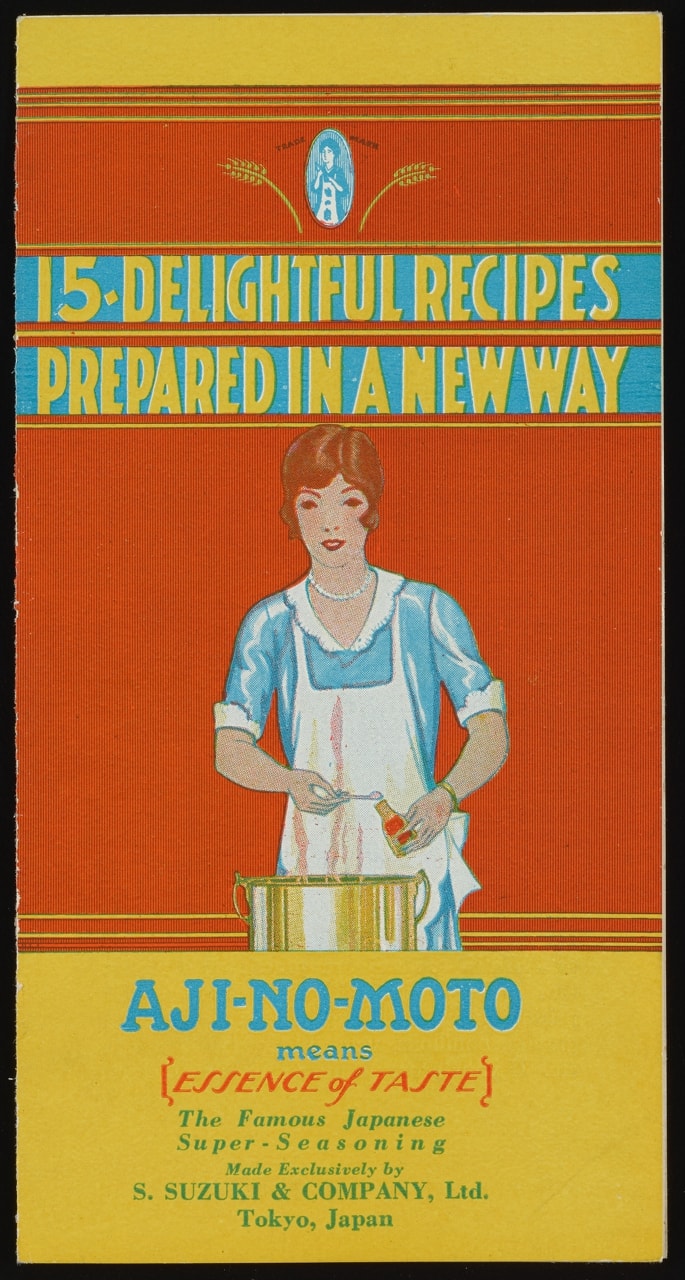

“With umami in its usage in English,” explains Sarah Tracy, a historian of science and food, “there is a very clear dotted line between the scandal and the moral outrage in the United States about MSG as a hidden toxin, and the shift in vocabulary in marketing—almost explicitly—of the Ajinomoto company [the chief producer of MSG] from talking about glutamate to talking about umami.”

Monosodium glutamate, or MSG, is a compound molecule that contains glutamate and binds with sodium in order to stabilize into something that can be packaged and sold in seasoning bottles, writes Helen Rosner. In essence, it’s umami in a shaker jar. MSG became widespread in the U.S. after WWII when the major players in industry and food science gathered for a convention “and they realized, ‘Oh, the Japanese military has been using MSG to great effect to improve troop morale and make things taste better,’” explains Tracy. At that point, Campbell’s Soup, among other companies, began to incorporate MSG as a flavor enhancer in order to make their products more competitive.

But for decades, MSG had a bad rap in the United States after the The New England Journal of Medicine published in the 1960s an infamous, controversial letter from a doctor about “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” The doctor wrote that he experienced symptoms similar to those of an allergic reaction when he ate food from a Chinese restaurant. Shortly thereafter, Science published a study in which researchers injected laboratory mice with MSG, which led to brain lesions and other neurological problems. Together, these publications were taken as an indictment of MSG.

It took a revolution in the world of food science to transform MSG’s image in the United States from a mass-produced, allergy-causing flavor enhancer to a secret miracle ingredient.

But there were problems with the Science study—researchers injected the MSG under the mice’s skin, while humans only eat MSG. Plus, the mice were injected with doses fit for horses. As for Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, “If you think you get a reaction to Chinese food, maybe you do—it’s just not the MSG,” John Fernstrom, a professor in the department of pharmacology and chemical biology at University of Pittsburgh, told Science Friday in 2015. “The thing is, there are all kinds of spices in Chinese food that are obviously plant-based—and people get allergic reactions to plants.” (Learn more about the history of MSG in the United States here.)

[Among a flock of fossils uncovered in China, the most primitive example of a beaked bird.]

For umami to gain acceptance in the United States, explains food historian Nadia Berenstein, Westerners would need a different kind of “proof” that MSG wasn’t harmful. That’s where molecular researchers come in.

“Umami particularly picks up speed in the 1990s, when taste receptors become the site at which taste becomes a real scientific thing,” explains Sarah Tracy. “I think directly in response to the turn in the 1980s and ‘90s of looking at food as science and food as something that can be molecularly tracked and interpreted… that is the general moment in which umami was being investigated,” she says.

In 2000, molecular biologists at the University of Miami published a paper in which they discovered a unique taste receptor for umami on the tongue of a mouse. The paper, which demonstrated that the presence of glutamate sent an electric signal to the brain and caused the taster to experience the sensation of umami, contributed to a sea change, says Tracy. “2000 was the ‘aha!’ moment,” she says. “We’ve got the receptors; umami is real.”

Here was the “proof”: “Once Western science can find the genetically linked biomedical pathway of umami reception, then the idea of the concept of umami as a basic taste modality that the Japanese have known since the beginning of the 20th century—only then does it becomes accepted,” Berenstein says. “Essentially, they needed a different kind of proof than what was possible or even imaginable earlier in the century.”

The food world has come to the rescue, too. The prolific chef David Chang has gone on the record in defense of MSG, points out Helen Rosner. So have food researchers, Anthony Bourdain, and the food writers Harold McGee and Rosner herself.

That’s all “part of this wider moment of excitement around chefs being research chefs and having research kitchens and not just preparing foods blindly in deference to tradition or french technique for example, but really trying to understand the ‘why’ behind what makes something taste good and how [we can] push that creative envelope,” says Tracy. “So [David] Chang is part of that moment of really innovative deconstructionist, fusion, post-post fusion of chefs who want to create new ways of things being delicious—and you have to go scientific in order to do that.”

[Who says we can’t reinvent the wheel?]

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.