The Origin Of The Word ‘Meme’

What does LOLcats have to do with evolutionary biology?

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

An evolutionary biologist blended the ancient Greek word mimeme—meaning something imitated—with the English word gene, to set the stage for LOLcats, Success Kid, Rickrolling, and so, so much more.

“Most of what is unusual about man can be summed up in one word,” writes the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. “Culture.”

But what does culture have to do with evolutionary biology? Like genes, he argues, cultural transmission creates a pathway to evolution.

“I think that a new kind of replicator has recently emerged on this very planet,” Dawkins writes. “It is staring us in the face. It is still in its infancy, still drifting clumsily about in its primeval soup, but already it is achieving evolutionary change at a rate that leaves the old gene panting far behind. The new soup is the soup of human culture.”

Dawkins needed a noun to describe this concept of the transmission of an idea. He initially toyed with the Greek word mimeme, meaning imitation, but he wanted something shorter that gestured to the English gene. He landed on meme.

[A new life support technology leaves a doctor wondering how far she’ll go to save a life.]

In Dawkins’ sense, a meme is simply an idea; it could be anything from fashion to a catchphrase to a method of building arches. So, how did we get from that to… this?

Internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch says we can trace the cross-pollination of Dawkins’ memes to the internet to a 1994 op-ed that Mike Godwin wrote for Wired.

If the name “Godwin” strikes a familiar chord, it’s likely because of “Godwin’s law:” an internet adage that every conversation will inevitably lead to a comparison to Hitler and the Holocaust. In the op-ed, titled ‘Meme, Counter-Meme,’ Godwin reveals the process of coining this law as an experiment in “memetic engineering.”

“He was seeing people propagating this meme of ‘everything can be compared to the Holocaust,’” says McCulloch. “And he thought this trivialized the actual horror of the Holocaust, and he said ‘I can’t just tell people to stop; I need to create a way that they’ll tell each other to stop.’” Godwin created this “law” and seeded it in various corners of the internet. When he took ownership and gave it a name, McCulloch cites this as the first transfer of Dawkin’s idea meme into the internet. Other memes from around the era include Poe’s Law (the idea that it’s nearly impossible to tell the difference between satire of extremism and actual extremism on the internet) and “the rules of the internet.”

Internet memes have certainly evolved since Godwin’s law—in fact, they might not even be text at all. McCulloch says, “I think an internet meme is a template of sorts that spreads by people creating their own versions of and innovations on that template.”

Soon enough, people incorporated images into internet memes. Remember the Dancing Baby, that 3D rendering of a baby boogieing to a Swedish rock song? That’s one of the first image-based internet memes, which spread primarily through email chains.

Today, many memes consist of an image with overlaid text, which can be altered. McCulloch cites LOLcats as one of the earliest examples of an internet meme as we know it today.

Consider the example of the “distracted boyfriend meme,” which originated with a stock photo. People repurposed the photo, and gave it new, specific life with every iteration.

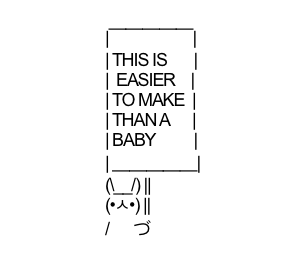

It’s been forty-two years since Dawkins gave birth to the idea of a meme as a “cultural gene.” That’s about a million lifetimes for internet memes. As the definition of a meme has evolved, does it still make sense to think of them as the genetic material of our wired culture? Perhaps the most obvious difference between genes and memes, says McCulloch, is that “It’s a lot easier to have a meme and propagate it than it is to raise a child.”

But the other key difference, she says, comes down to intention.

“Sexual selection describes a degree of intentionality,” she says. “But say I’m sexually attracted to tall people. I can choose to reproduce with a tall person, but it doesn’t guarantee that my hypothetical child will have tall genes. But if I like LOLcats or the Sign Bunny meme, I can choose to create a Sign Bunny.”

How does Dawkins himself feel about all this? When asked by Wired in 2013 about memes evolving into the internet sense, he said: “The meaning is not that far away from the original. It’s anything that goes viral.” In fact, in the final chapter of The Selfish Gene, Dawkins invokes the metaphor of a virus. “So when anybody talks about something going viral on the internet,” he told Wired, “that is exactly what a meme is and it looks as though the word has been appropriated for a subset of that.”

Well…

So, even if memes aren’t a perfect metaphor for sexual reproduction, they have been adapted to flourish in the different ecosystems that make up the internet. The ones that survive best—whether they’re Arthur’s Fist, Homer Backs Into Things, or Is This a Pigeon?—do so because they fit the idea they convey so well.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.