The Origin Of The Word ‘Humor’

From pseudoscience to Shakespeare, it’s no laughing matter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

1340 is the first written record of the word humor entering Middle English.

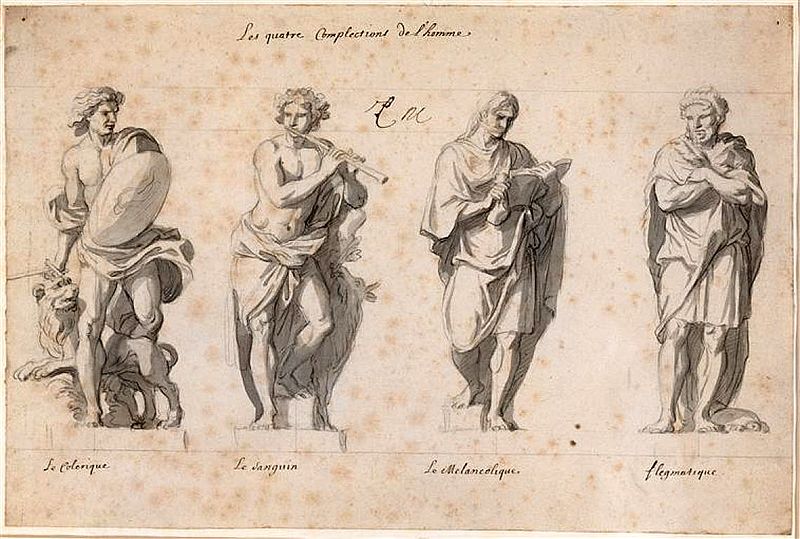

Traditionally, humor is believed to have grown from the Latin word for “liquid” or “fluid.” It originally referred to the four chief substances that ancient Greeks believed flowed through our bodies: yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm. In ancient humoral theory, each of these substances was associated with a personality trait, and each person’s unique mixture dictated their disposition. But today, there’s a lot of serious science behind laughter.

Things aren’t off to a great start when Petruchio and Kate arrive at an inn in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. Petruchio refuses to let his wife eat, claiming that the meat is burned. He plots to complain about the bedding, and deprive her of sleep. It turns out Petruchio is intentionally aggravating Kate, who he describes as a “falcon” that must be trained, “and thus [he’ll] curb her mad and headstrong humour.”

Kate and Petruchio are both cholerics, one of four character types based on the ancient Greek theory about the humors that dictate our temperaments. In early Western physiology, ancient physicians like Hippocrates and Galen believed that not only our temperament, but also our overall health, hinged on the balance of the four fluids that flowed through us and their interplay with our environment and lifestyle.

The “ideal” person contained a healthy and balanced mixture of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. In fact, Hippocrates believed an overabundance of black bile in an organ caused cancer, and this theory held for over 1,300 years through the Middle Ages (autopsies were banned for religious reasons).

While we now consider the humoral theory pseudoscience, it played a vital role in medical development—it was the first organized theory that indicated that illness stemmed from natural causes, rather than something supernatural or cosmological. That caused physicians to really start paying attention to their patients. It was easy to dismiss factors like diet and exercise when the cause of an ailment was supernatural; not so when it could be cured through rebalancing. Early physicians like Galen were tasked with diagnosing which humor was out of balance, and prescribing treatment to restore it to equilibrium. Too little blood? Take a long drink of the fluid. Too much black bile? Purge it out via sweating, vomiting, or an enema.

But while the Greeks thought humoral balance made for a healthy, rational person, it didn’t make for particularly interesting characters.

“In Elizabethan times, there was quite a fad for the writing of plays about people who had some pronounced one-track personality,” writes Isaac Asimov in his book Words of Science. Beside the eccentric Kate and Petruchio, you can see the same idea in 16th-century playwright Ben Jonson’s Every Man in His Humour, in which the characters can’t shake their overbearing humoral traits.

When it came to temperament, that balance—or imbalance—of the humors dictated whether a person was in “good” or “bad humor.” Cholerics, like Kate and Petruchio, were characterized by an excess of yellow bile, which resulted in an aggressive and fiery personality. Too much black bile induced sadness, or a melancholic disposition (the Greek word melas means “black”). A phlegmatic person tended toward easy contentment, and a person with too much blood grew warm and sanguine.

“William Shakespeare’s plays provide examples of all four temperaments, but it’s the cholerics who provide much of the drama,” writes Nelly Ekström for the Wellcome Collection. “If it was all down to the brooding melancholics, the lazy phlegmatics and the friendly and pleasure-seeking sanguines, not much would happen.”

“[Elizabethan-era] plays were generally comedies and the characters, each harping away at his particular personality trait, were laugh-provoking,” writes Isaac Asimov. “For that reason, the word humorous has come to mean ‘funny.'”

Humoral theory may be long gone, but scientists are still studying laughter—and it has very little to do with comedy.

Recently, neurologist Sophie Scott of University College London bumped into another woman while walking. Afterwards, they did something interesting—they both laughed.

“We weren’t amused, but we were both kind of saying, ‘I’m ok, you’re ok, I’m not trying to hurt you,’” explains Scott. “But imagine if I’d bumped into her and I’d laughed and she’d gone, ‘Why are you laughing? You just hurt me’… It’s simple things like that that rest on a very, very complex set of assumptions that we’re both making in the breathtaking seconds before we actually start laughing.”

Laughter hasn’t been studied nearly as widely as reactions around emotions like stress or anxiety. Yet it is primarily a social behavior, explains Scott, which means that it can tell us a lot about how we relate to and communicate with other humans. Laughter is universally recognized, and we’re 30 percent more likely to laugh when we’re around other people. Within those interactions, though, we’re not usually chuckling in response to a joke; we use laughter to signal agreement, or show affection, or demonstrate that we understand someone. Laughter does a lot of the “emotional work” in our interactions, says Scott, and “when something goes wrong with your laughter, that can have really big impacts on your day-to-day interactions with people in all kinds of situations.”

“What you’re always doing when you hear somebody laughing, particularly as an adult, you’re trying to work out why that person’s laughing, what’s their intention behind it,” says Scott. “We use laughter in this very complex way. Laughter itself is quite simple as a sound, but actually we read into it a phenomenal amount. And we will rely on other people doing that.”

Scott says we can also think of laughter as more than a social signal. It can be a tool, too, like nervous laughter.

“If you can in a difficult situation use laughter to make yourself both feel more positive and less stressed, then that’s a very nuanced way of using laughter to actually negotiate yourself to a better place in terms of emotions,” Scott says in a video for the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. “And that’s really interesting because it’s not just sending a signal there, it’s something you’re actually using to regulate an emotional state—and regulate it in a positive way.”

The reasons for laughing may be deeply complex, but on another level, it’s also a very basic, ancient act. Scott says laughing is more similar to an animal call than speech—and we may be tapping into an ancient response every time we let loose a chuckle.

“Laughter is older than us,” says Scott. “We see it in very recognizable forms in rats and apes.”

Other mammals produce nonverbal vocalizations mainly via the midline system that runs up the middle of the brain, explains Scott, and that same system is almost certainly important in humans, too. “Speech involves a completely different brain system,” she says. For Scott, that’s one of the big questions about laughter: “Is it the case that when you’re laughing you kind of drop into this really ancient way of producing sounds? Or is there a more complicated sort of interaction? Or are you using it as an interplay between the old and the new?”

We may associate laughter with lightheartedness. But really, there’s nothing funny—or humorous—about it.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.