The Origin Of The Word ‘Helium’

Astronomers thought the element could only be found in the sun.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

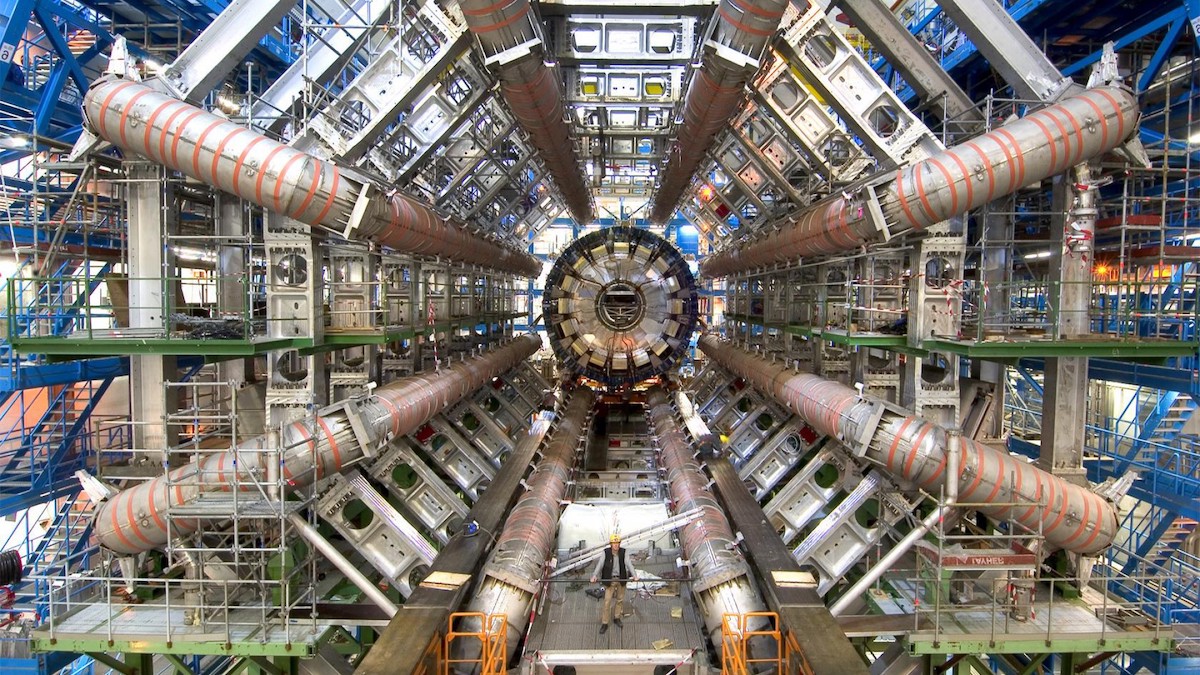

Helium comes from the Greek word for sun, helios. That connection to the sun is the reason why, for nearly three decades after it was first observed, chemists dismissed the element that we use today for everything from filling party balloons to cooling the Large Hadron Collider—and now helium is rapidly diminishing.

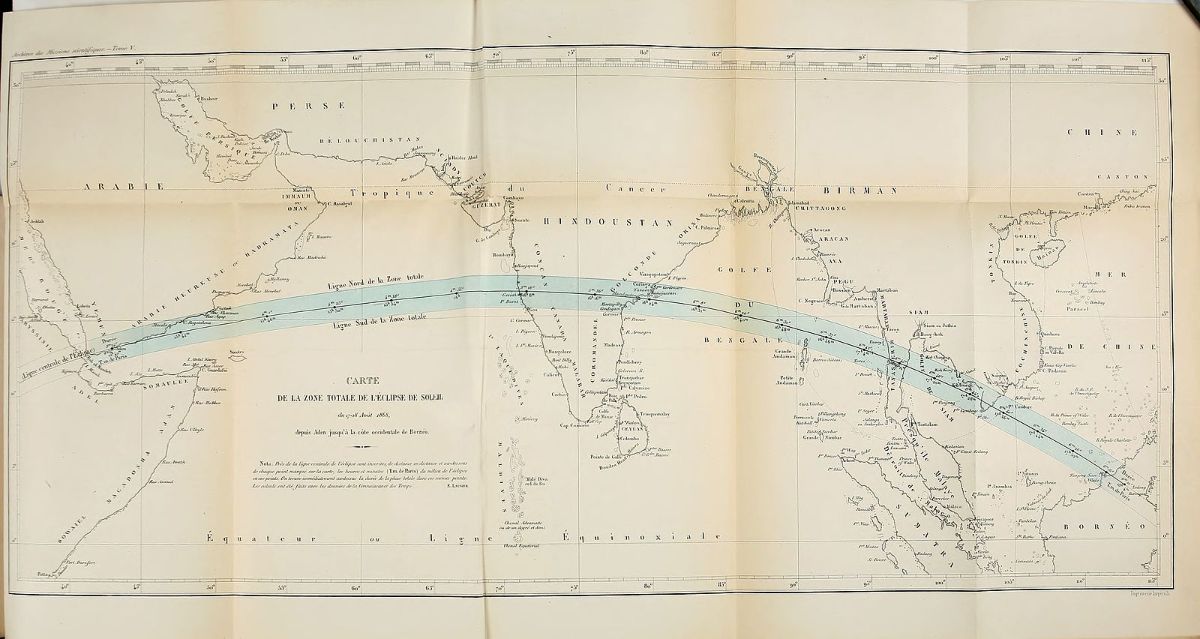

On August 18, 1868 in Guntur, India, the French astronomer Pierre J. C. Janssen positioned his prism in the brief moments of darkness during a total solar eclipse. Janssen was one of the many astronomers feverishly anticipating the eclipse, which would be the first since German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff theorized nine years earlier that scientists could use spectroscopic analysis to figure out the chemical composition of unreachable bodies like the sun. As white light passes through a prism, the light splits into rainbow lines of colors, and each element corresponds to its own singular pattern of colored lines. Astronomers believed an eclipse was the best time to make those observations—the blanket of darkness that fell across the Earth as the moon moved between it and the sun would block the glare from the sun.

When the light passed through the prism, Janssen noticed something funny. Among the usual spectral lines, a yellow line blazed through, writes Mary Elvira Weeks in Discovery Of The Elements. The line was similar—but not quite identical—to that produced by sodium. In fact, the line was so bright that Janssen suspected that it could be observed in normal daylight.

Meanwhile, working simultaneously and independently 5,000 miles away, the British astronomer Sir Joseph Norman Lockyer had the same suspicion. He was able to observe solar prominences in broad daylight—and also noticed the odd yellow line. “[He] compared the position of this line with those of similar lines produced by various elements,” writes Isaac Asimov in his Words of Science, “and decided that this new line was produced by an element in the sun that was not present, or had not yet been discovered, on earth.” Lockyer called the new element helium, after the Greek word for sun. Both Janssen’s and Lockyer’s papers describing their observations landed at the French Academy of Sciences on the same day, and both men received credit for the discovery of the “new” element.

But it took a long time for others to get on board with helium. For over a quarter of a century, other scientists dismissed the funny yellow light in the sun. It wasn’t until a Scottish chemist named Sir William Ramsay recreated an experiment, treating a uranium mineral with acid and studying the resulting spectral lines. Ramsay sent a sample to double-check with Lockyer, who wrote: “When I received it from him, the glorious yellow effulgence of the capillary, while the current was passing, was a sight to see.” It was helium—and it was on Earth.

Today, the sun element seems to be everywhere on Earth. We inflate countless party balloons with it. We blend it with oxygen in high-pressure environments to allow us to dive deep into the ocean, and we use it to cool giant electromagnets like the Large Hadron Collider.

But now, we’re running out of it.

“Helium is constantly being produced,” says retired chemist and American Chemical Society member Richard Sachleben. “Uranium and thorium are decaying down in the earth’s mantle and crust. And helium, which is the final product of that, comes sneaking up through it and some of it escapes through the surfaces and [into] the atmosphere, and some of it gets trapped in formations in the ground.”

The thing is, says Sachleben, that’s a really slow process—it can take hundreds of millions of years.

“We’re using what you might call fossil helium, just like fossil fuels,” he says. “It’s what was trapped in the earth’s crust in different formations over time. And we’re sucking it out of there [quite] fast compared to how it was actually trapped and stored.”

Demand for the element has increased by 10 percent per year over the last decade, and the price has skyrocketed by more than 250 percent. As certain industries grow, so does the demand for helium. The element is used in manufacturing optical fiber, and to cool military aircraft, for example. In these cases, there are very few substitutes—if any—for the element.

As the helium supply dwindles, “helium is expected to continue to be essential in enabling the development of such critical technologies in the future,” according to a report in Nature Resources Research. The welding industry uses helium as a cover gas when working with specialty metals, so they don’t react with oxygen in the air. Liquid helium has a boiling point of roughly 4 degrees Kelvin, or -452.47 Farenheit, which makes it useful for cooling superconducting magnets in everything from your local hospital MRI machines to particle accelerators at CERN.

When Qatar, which is the world’s second-largest helium supplier, was blockaded in summer 2017, the effects reverberated in both labs and companies across the globe. So, what are scientists and industrial users doing to prepare?

“Bottom line is, they’re not,” says Sachleben. “If the price of helium goes up enough, or the need for it goes up enough, there’s two sources. One is: Find more wells that have helium in them, and that’s possible. And the other one is: Get the helium out of the ones that aren’t worth processing right now.”

For example, he says, if we sucked all the helium out of all the natural gas we use, we’d probably be in pretty good shape. Right now, producers likely wouldn’t be able to sell that helium for a price higher than what it cost to extract it.

But someday, they might.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.