The Origin Of The Word ‘Crater’

It has more to do with wine than lava.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

At any given moment, an estimated 20 volcanoes are erupting on Earth. The word crater stretches back to ancient Greece, and has a lot more to do with wine than lava. In fact, the Greek kratēr comes from kerannynai, which means “to mix.”

There’s a scene in Homer’s Iliad where Odysseus, the Greek king of Ithaca, competes in a footrace. The prizes are fit for royalty. The runner who came in third would walk away with nearly 28 pounds of gold. The second-best runner would receive a fattened ox.

And for the winner, the grandest prize of all: “a mixing-bowl, beautifully wrought, of pure silver… and far [exceeding] all others in the whole world for beauty,” crafted by artisans in Sidon and carried across the sea by the Phoenicians. When the runners took off, Odysseus prayed to the goddess Athena to lighten his feet. He flew across the finish line, and earned the prized vessel.

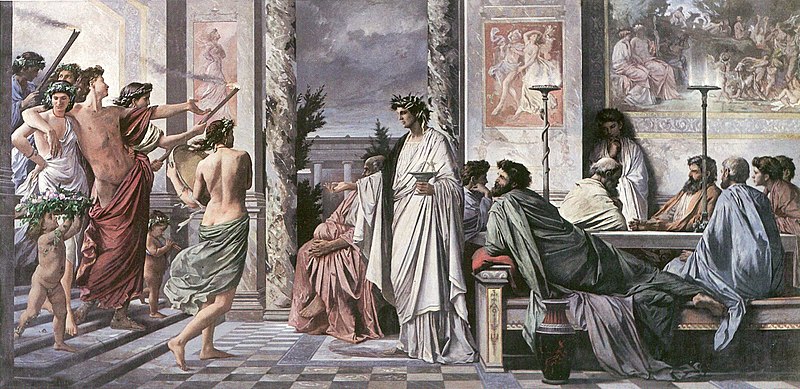

The mixing bowl was called a krater, and the ancient Greeks used it to mix water with wine. Kraters were ubiquitous; take a look at any depiction of a symposium scene—when men gathered to exchange ideas, philosophize, dine, and, of course, drink—and you’ll likely notice an urn with a foot and a large opening positioned prominently in the room.

Unlike modern varieties, wine in ancient Greece was typically aged in leather or clay containers, resulting in a very acidic taste and spiking the alcohol content to about 16 percent (compared to today’s wine, which typically contains roughly 12 to 13 percent). It was considered “uncivilized” and “barbarian” to drink the wine undiluted, so the Greeks would mix roughly two parts wine with five parts water in the krater before passing around the wine in a communal cup. In fact, in a surviving fragment of a lost play, the 4th century poet Eubulus wrote:

“For sensible men I prepare only three kraters: one for health, the second for love and pleasure, and the third for sleep. After the third one is drained, wise men go home. The fourth krater is not mine any more—it belongs to bad behavior.”

Pinpointing exactly why the word expanded and seeped into our everyday language remains a mystery. But eventually krater morphed into crater, and came to describe any bowl-shaped depression like the one in those ancient Greek vessels. The English cleric and traveler Samuel Purchas was the first to apply the word to the mouth of a volcano in his 1613 work Purchas His Pilgrimage, which covers theological and geographical history from Asia to the Americas.

Purchas recounts a violent volcanic explosion in Mexico, the ash of which burned the indigenous people’s crops: “The Vulean, Crater, or mouth whence the fire issued, is about halfe a league in compasse.” And it was Ralph Waldo Emerson who first penned a reference to the craters of the moon in his Conduct of Life in 1860: “Every man wishes to see the ring of Saturn, the satellites and belts of Jupiter and Mars, the mountains and craters in the moon: yet how few can buy a telescope!”

Ancient kraters may have instigated some libated singing, but some volcanic craters make their own music. Jeffrey B. Johnson, associate professor of geophysics at Boise State University, likes to compare volcanoes to enormous musical instruments.

Active volcanoes produce a wave phenomenon called infrasound, which reverberates against the boundaries of the crater, creating resonance. The infrasound is too low for the human ear, but instruments can detect them, in some cases from thousands of miles away. Like an enormous pipe organ or trombone, the geometry of the crater shapes the sound it produces, giving each volcano an individual infrasound “voiceprint.” These voiceprints can tell us valuable things about what kinds of rumblings are normal in a volcano—and when things become not normal. Changes in the way each volcano “speaks” could potentially signal an impending eruption.

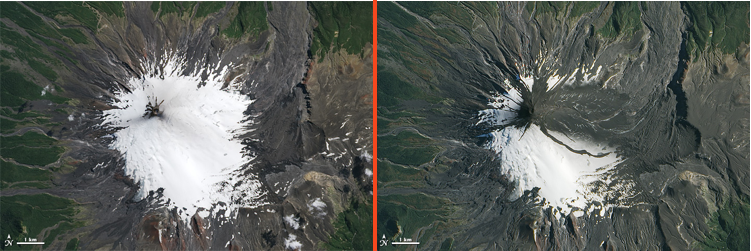

Consider the case of Volcán Villarrica in Chile, where major eruptions occur about every 30 years.

“[For years], Villarrica had been in its happy place, which was just sort of this lava lake bubbling away deep within the crater,” says Johnson. That all changed in 2015, when the volcano erupted catastrophically, resulting in widespread evacuation and major damage. While other typical volcanic indicators were ambiguous, when Johnson and the team of researchers analyzed the infrasound records, they noticed that in the days leading up to the eruption, the volcano’s infrasound changed drastically.

“The infrasound changed its tune from being a resonating system with a nice oscillation and sort of a musical tone to being thunk-like,” he says. “So what can cause that?”

The researchers determined that just before the eruption, the volcano’s lava lake—which had been peacefully gurgling down below—was suddenly sitting up high in the crater. As the lava lake crept up, it effectively shortened the length of the “trombone slide,” altering its infrasound. “As you might imagine, when a lava lake starts to move up into the upper section of the conduit for the first time in 30 years, then you should pay attention,” says Johnson.

Of course, Johnson and his team made this connection after the fact, and weren’t able to forecast the Villarrica eruption. “It was a case of the right place at the right time,” he says. The team just happened to have already been monitoring the site for a different research project, unknowingly chronicling the lead up to the eruption. Major eruptions like the one at Villarrica don’t happen very often, and researchers can’t camp out everywhere, all the time—but if they were able to respond to the very first indication of volcanic unrest, Johnson says, it might be a step toward using infrasound to forecast eruptions.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.