The Origin Of The Name ‘Spanish Flu’

It’s a misnomer that endured for a century.

The Spanish flu wasn’t Spanish at all. Listen to this episode on the new Science Diction podcast!

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

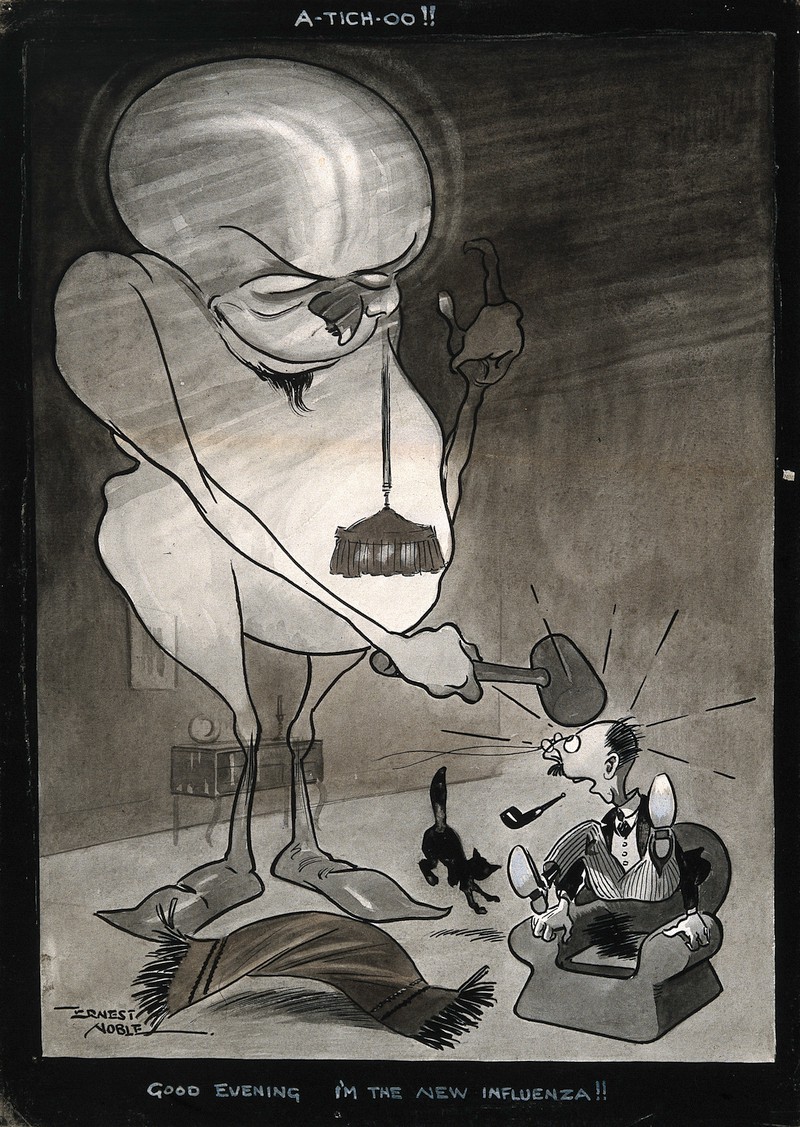

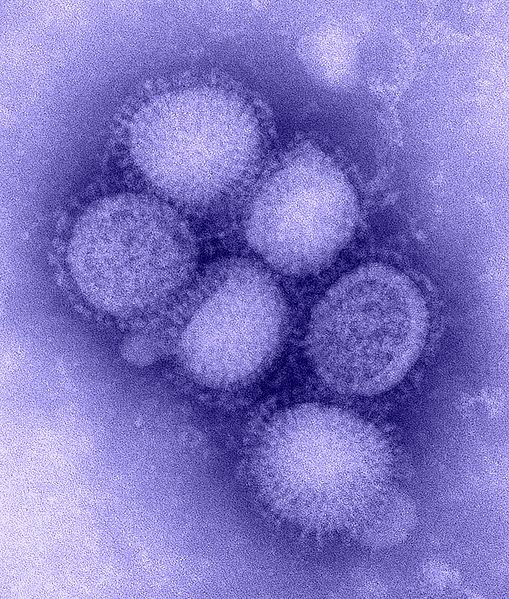

In ancient times, before epidemiology science, people believed the stars and “heavenly bodies” flowed into us and dictated our lives and health—influenza means “to influence” in Italian, and the word stems from the Latin for “flow in.” Sickness, like other unexplainable events, was attributed to the influence of the stars—and they gave the name influenza to one of the most common ailments, according to Isaac Asimov’s Words of Science. But the name for the infamous 1918 outbreak, the Spanish flu, is actually a misnomer.

On May 22, 1918, Madrid’s ABC newspaper published news of the spread of a strange illness that had begun infecting the people of Spain. The virus was mild, but sudden. People collapsed in the street; a week later, even King Alfonso XIII grew sick.

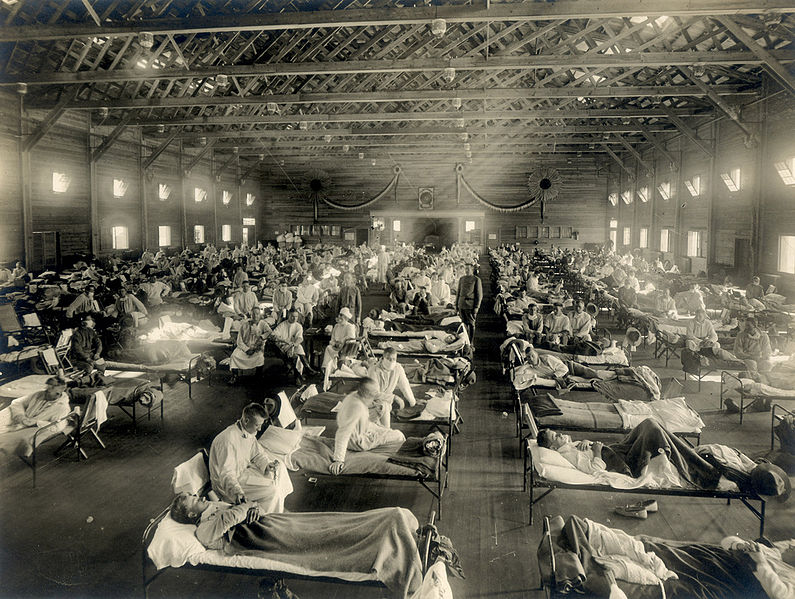

One month later, the poet Wilfred Owen was stationed across the continent in Scarborough army camp. While he was huddled in a tent, waiting to see if he would be sent back to the front lines of World War I, Owen wrote his mother a letter. “‘STAND BACK FROM THE PAGE! and disinfect yourself,’” the letter begins. “Quite 1/3 of the Batt and about 30 officers are smitten with the Spanish Flu. The hospital overflowed on Friday, then the Gymnasium was filled, and now all the place seems carpeted with huddled blanketed forms…. The boys are dropping on parade like flies in number.”

It’s tough to exaggerate the devastation of the 1918 influenza pandemic. An estimated one-third of the world’s population became infected over its course; at least 50 million people died. In some cases, there was simply no time to build enough coffins to house the dead, so people were buried directly in the ground, a process one survivor referred to as “plantings.” In one Pennsylvania town, the death rate was was so high that a high school functioned as a funeral home—bodies would be displayed in a window so loved ones could attend the viewings from the safety of the sidewalk.

In a Times of London editorial that forecasted the impending end of the “mild” illness, the devastating outbreak was dubbed the “Spanish flu.” But that name was a misnomer that would endure for a century.

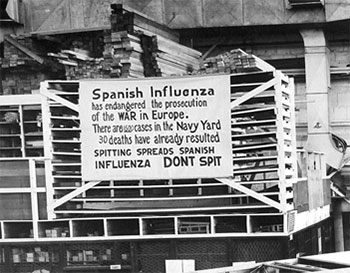

By the time the “Spanish flu” broke out in the spring of 1918, the United States, France, and Germany (among other countries) were embroiled in World War I. “WWI undoubtedly added to the horrors of Spanish flu,” Catharine Arnold, author of the book Pandemic 1918, wrote in an email to Science Friday. “Global mobilization of millions of troops meant that the flu spread swiftly, carried from the New World to the old on troopships, and fanning out from ports as far apart as India, Africa and Russia. The war turned the world into a giant petri dish in which the virus could spread AND evolve.”

One country that wasn’t involved in that worldwide exchange? Spain.

The American, French, and German press were most likely reluctant to let the cat out of the bag about the pandemic sweeping the country and causing their troops to drop like flies, according to an article from Clinical Infectious Diseases. In the United Kingdom, newspapers were forbidden from discussing the outbreak in detail under the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914. High-ranking British civil servant Sir Arthur Newsholme refused to take measures like instituting quarantine and shutting down public transport because he believed focusing on the war effort should claim top priority, says Arnold.

Spain remained neutral in the war, and, as a result, wasn’t subject to wartime precautions and censorship rules. The Spaniards had no reason to keep mum, and ABC, one of the national Spanish newspapers, was one of the first, if not the first, to report on the illness snaking through the country. The pandemic didn’t originate in Spain—in fact, it wasn’t nearly as bad there as it was for other countries. Even today, experts aren’t certain where the outbreak originated. Some say China, some say the American Midwest, and others suggest France. But one thing’s for certain—it wasn’t Spain.

“Nobody calls it [the Spanish flu],” says Albert Bosch, president of the Spanish Society for Virology. “It just happened to be the place where it was reported, and that’s it.” Arnold says the Spaniards themselves had different names for the virus—sometimes “the French flu” for their historic rival, sometimes “Naples Soldier” after a popular musical—but it was the name in the Times that would stick.

No flu season since has come close to the devastation of the 1918 pandemic, but for many flu season can be a stressful time of year.

For someone like Matt Smith, who suffers from cystic fibrosis, even a minor bout of the flu can be a life-threatening illness. If the average person comes down with the virus, she may spend a few days at home feeling lousy on the couch; Smith could wind up in the hospital for weeks.

“I’m constantly thinking about infection control,” Smith told Science Friday in November. “Anything that comes into the house, whether it’s packages or people, I spray it down with Lysol. When I go out in the public I wear a mask, and I’m always sort of vigilant for people who might be sniffling or coughing and do my best to run away from them as fast as I can if I hear that.” Out of caution, he skipped his 25th high school reunion.

Every flu season is different. The virus is always changing; tiny alterations occur in its genes as the virus replicates.

“Influenza can infect a wide variety of hosts, namely birds, but also [pigs], dogs, cats, ferrets, etc. So you can have the virus circulating and varying in all these hosts. Then you have a highly variable virus,” says Bosch. “And then, you must prepare a vaccine. And in order [for it] to be an affordable vaccine, you can include three, maybe four, strains.”

On top of these variables, researchers must prepare the vaccine about six months before the start of flu season, based on what they’ve seen circulating so far. “It’s a gamble,” says Bosch. “You have a lot of clues; it’s not a blind gamble. It’s based on science, what’s been in the past circulating everywhere, and what you expect could happen.” As of January 12th, the Centers for Disease Control estimate nearly 10 million people have flu-like symptoms.

Of course, the flu shot doesn’t guarantee immunity; it’s still possible to catch a strain of the virus not covered by the vaccine. But chances are, you won’t. Studies show that, in years when the vaccination matches the strains circulating, it cuts the risk of sickness by 40 to 60 percent, and prevents millions of illnesses each year. (For more information about vaccines, check out this Science Friday resource.)

“I know some people are kind of apprehensive about getting the vaccine,” says Smith. “But I’d like people to think of it as an opportunity to help out other people. And it’s not just people with a rare lung disease like me. It’s anybody with asthma or COPD or kidney disease or heart disease or the elderly or young kids. There’s millions and millions of vulnerable people so I hope that people will make an effort to go out and get the shot.”

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.