World War I’s Operation Face Lift

Medical historian and author Lindsey Fitzharris explores the history of facial reconstruction surgery, starting with a ballerina’s rump.

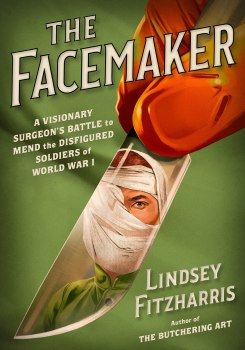

The following is an excerpt from THE FACEMAKER: A Visionary Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I by Lindsey Fitzharris.

THE FACEMAKER: A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

The war and all its horrors were as yet unimaginable as Harold Delf Gillies and his wife wove their way through Covent Garden. Slender, with a beaklike nose and dark brown eyes that often glinted with mischief, the thirty-year-old surgeon had a habit of slouching that made him seem shorter than his five foot nine inches. The couple pushed on through the throng of stallholders and hawkers who were concluding their day’s business on the cobbled streets. In the spring of 1913, London was a far more commanding presence in the world than it would be on the cusp of the Second World War, twenty-six years later. With over seven million people living there, this bustling metropolis was larger than the municipalities of Paris, Vienna, and St. Petersburg put together, and it was home to more people than Britain and Ireland’s sixteen other largest cities combined.

London wasn’t just big. It was also wealthy. The city funneled ships into and out of the North Sea via the Thames as they exported and imported goods from all points of the compass. It was one of the busiest and most prosperous ports in the world, and a vast emporium of luxuries. Dockers unloaded regular shipments of Chinese tea, African ivory, Indian spices, and Jamaican rum. With this influx of goods came people from countless nations, some of whom decided to settle in the capital permanently. As a result, London was more cosmopolitan than ever before.

Londoners worked hard and played harder. There were 6,566 licensed premises that fueled the city’s favorite pastime—drinking—and ensured that the police force was kept busy. London boasted 5 football teams, 53 theaters, 51 music halls, and nearly 100 cinemas that would see weekly attendance triple by the end of the decade.

On that unseasonably warm spring evening, the Royal Opera House was staging its first performance of Verdi’s Aida for London’s more well-to-do music lovers. Gillies had been given tickets by his boss, Sir Milsom Rees, a laryngologist who specialized in illnesses and injuries of the larynx, or voice box. As medical consultant to the Royal Opera House, Rees was charged with tending to the throats of its famous singers. On this occasion, however, he was indisposed, so he sent his young protégé to deputize for him.

Three years earlier, Gillies had acquired his cushy position at Rees’s medical practice, situated in the fashionable district of Marylebone, largely by happenstance. When he interviewed for the job, he had just completed his clinical studies at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. During that time, he had shown a keen interest in otorhinolaryngology, a surgical subspecialty that deals more broadly with conditions of the head and neck. Those who work in this field more commonly refer to it as ENT (ear, nose, and throat). The chief physician, Walter Langdon-Brown, considered him to be one of the ablest in his class. But it wasn’t Gillies’s surgical skills that had landed him the job with Rees across town. Rather, it was his reputation as an excellent golfer that had caught the older doctor’s attention.

At the time, Gillies had just reached the fifth round of the English Amateur Championship. During the job interview, Rees brought out his own golf clubs for Gillies to inspect. As the laryngologist demonstrated his swing, Gillies grew impatient. “This is ridiculous. When is he going to talk about the job?” he wondered. As it turned out, they never did find a chance to discuss the terms of employment. A short way into the interview, a patient arrived, prompting Rees to rush a bewildered Gillies from his office. Just as he was closing the door, Rees briefly swung his attention back to his would-be employee and offhandedly remarked, “Oh, my dear fellow, I’d forgotten! Well, how would five hundred [pounds] a year suit you? Any private patients you pick up you can keep for yourself. All right?” Gillies—who had been making fifty pounds a year at the hospital—was elated at the prospect of making ten times as much money as an ENT specialist in Rees’s private practice. It was not the last time that admiration for Gillies’s sporting prowess would open the door to opportunity.

Gillies had always been a high achiever. He was a man for whom talent—be it athletic, artistic, or academic—was “mysteriously inherited rather than laboriously acquired,” as his early biographer Reginald Pound observed. The youngest of eight children, Harold Gillies was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, on June 17, 1882. His grandfather John had immigrated there from the Scottish Isle of Bute in 1852, bringing his eldest son, Robert, along with him. Robert eventually set up business as a land surveyor, and it was in Dunedin that he met Emily Street, the woman who would become Harold’s mother. The two fell in love and married shortly thereafter.

Gillies spent the first few years of his childhood tottering around the cavernous rooms of a Victorian villa. His father, an amateur astronomer, had commissioned the construction of an observatory with a revolving dome on the roof of their ornate stone residence. Robert Gillies christened the family home “Transit House.” He chose the name in honor of the New Zealand astronomers who had made important observations of the 1874 transit of Venus when the planet passed across the face of the sun.

Gillies was a precocious child who loved to spend time roaming the expansive countryside around his home with his five older brothers, who would prop him up in the saddle of Brogo, the family mare, and bring him along on hunting and fishing expeditions. Early in life, Gillies fractured an elbow while sliding down the long banisters in the family home, which permanently restricted the range of motion of his right arm. It was a disability that later spurred him to invent an ergonomic needle-holder for use in the operating theater to compensate for his limited ability to rotate his hand.

Two days before his fourth birthday in June 1886, Gillies’s idyllic childhood was shattered. That morning, one of his brothers climbed the stairs to check on their father, who had complained of feeling unwell the previous evening. When he entered the bedroom, he found Robert Gillies alert and in good spirits. His father told him that he would soon join everyone for breakfast in the dining room downstairs. The boy hurried off to tell his family the welcome news.

The kitchen sprang to life as pots and pans were pulled from high shelves, and the kettle whistled at the end of the water’s slow boil. But as the minutes ticked by, Gillies’s brother grew increasingly concerned. After half an hour, he climbed the grand staircase once more. A shock awaited him in the bedroom. Lying motionless on the mattress was Robert Gillies, dead from a sudden aneurysm at the age of fifty.

Following her husband’s death, Gillies’s mother moved herself and her eight children to Auckland so that they could be closer to her own family. When Gillies was eight years old, he was sent to England to attend Lindley Lodge, a boys’ preparatory school near Rugby, in the heart of the country. Four years later, Gillies returned home to continue his education in New Zealand, but he wouldn’t remain there for long. In 1900, at the age of eighteen, he moved back to England in order to study medicine at Cambridge University. His decision to become a doctor came as a surprise to everyone. It was a career he purported to have chosen to differentiate himself from his brothers, who were lawyers. “I thought another profession should be represented in the family,” he joked.

At Cambridge, he gained a reputation for being something of a maverick after he spent his entire scholarship fund on a new motorcycle. He wasn’t afraid to challenge his professors and could often be found arguing with the anatomical demonstrator in the university’s dissection lab. Despite this lack of deference for authority, he was eminently likable and admired by teachers and classmates alike for “his happy temperament and his smile that broke into uproarious laughter.” His popularity won him a nickname, “Giles,” which stuck with him his entire life.

In spite of his rebellious spirit, Gillies had an orderly mind with an affinity for rules and boundaries— especially if he was the one setting them. For the duration of his studies, he lived in a Victorian terraced house with five other young men. As students are wont to do, they came and went as they pleased. Gillies noticed that not every housemate was present at mealtimes, so he devised a system to keep track of costs. Each person was required to mark down his attendance at meals in addition to the number of “units” he consumed, as well as the cost per unit. One of his fellow lodgers called it a “most original and ingenious scheme” that ensured equity and helped keep costs down for everyone. But his mates were less impressed when Gillies charged each of them interest on money that they owed him after he had settled a household debt. For Gillies, fairness was all.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

It was during his studies that he developed a serious interest in golf, routinely swapping his pen for a hickory-shafted driver. He tried out for the university’s golf team on a whim after traveling to Sandwich for a party with some classmates. He had brought his golf clubs with him so that he could play a round on the famous course there, where a match between Cambridge and Oxford was going to be held a few days later. After the party was over, Gillies boarded a return train. At the last second, he had a change of heart. He grabbed his clubs and hopped off the carriage just as the locomotive began steaming out of the station. Shortly afterward, he was welcomed onto Cambridge University’s golf team.

Gillies spent an inordinate amount of time locked away in the bathroom, which must have raised a few eyebrows among his housemates. His daily ritual in the tiny room was to plant his feet on the same two patches of linoleum and practice his swing in front of the mirror. His friend Norman Jewson, who would later become a famous architect, was struck by Gillies’s “immense powers of concentration, and will power.” Those who knew him described his talent for golf as “supernatural.” In time, his patients would come to see his skill as a plastic surgeon in a similar light.

As the years passed and his studies progressed, Gillies began to display an aptitude for surgery— which was not surprising, given his obsessive attention to detail. He was driven in a way many young men of his social class were not, often sequestering himself in a library while his peers were out socializing. One friend remarked, “Whatever he decided to do he did.” His determination would serve him well in life.

This was never truer than when it came to matters of the heart. Although Gillies had vowed never to marry a nurse, he found himself suddenly and hopelessly in love with Kathleen Margaret Jackson, a nurse at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, where Gillies had been working during his clinical studies. But there was a problem: another doctor was also courting her.

Never one to shy away from a little competition, Gillies redoubled his efforts. One evening, he hired a hansom cab and invited Kathleen out for a ride. Once in the buggy, Gillies had the cabbie drive them continuously through the streets until she accepted his proposal. The stern etiquette of the day required that nurses live on hospital grounds and remain unmarried, so Kathleen resigned from her job shortly after becoming engaged. The two were happily married six months later on November 9, 1911. By then, Gillies was ensconced in his lucrative position at Rees’s private medical practice.

It was with his wife, Kathleen, that Gillies was attending the performance of Aida in Covent Garden’s grandly porticoed opera house on that pleasant spring night. The couple had left their firstborn— a little boy named John who would become a POW during the Second World War when his Spitfire was shot down over France—in the care of family. As the curtain fell on the opera’s first act, a white- gloved attendant approached Gillies discreetly and requested his presence backstage. Given the habitually light duties of his boss on these occasions, Gillies expected to have to do little more than spray some sort of soothing balm into the overworked throat of a singer. Instead, he found one of the dancers injured and in a state of undress. Felyne Verbist, the Belgian prima ballerina, had sat on a pair of scissors, sustaining a deep puncture wound to her shapely backside. Gillies set to work bandaging the tender spot.

As he returned to his seat, he wondered how he would explain his prolonged absence—and the details of the “throat” case—to his young wife. Throughout the rest of the performance, he had trouble concentrating on anything “but the slight lump in the beautiful dancer’s costume where my rather rough-and-ready dressing bulged.”

It was an incident that Gillies would recount many times in later years, as if removing the pointed end of a pair of scissors from a ballerina’s buttock was the crowning glory of his career.

Excerpted from THE FACEMAKER: A Visionary Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I by Lindsey Fitzharris. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by Lindsey Fitzharris. All rights reserved.

Lindsey Fitzharris is a medical historian and author of The Facemaker.