How Shells Tell Secrets Of The Sea

Seashells have played many roles throughout history, from money to jewelry. But they also hold secrets of the ocean’s health.

The following is an excerpt from The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Oceans by Cynthia Barnett.

One hundred thousand years ago, a human cousin walked a rock-ribbed beach along the Mediterranean Sea, her head lowered and her large eyes scanning the shoreline. Now and again she stopped, bent her strong body, and picked up a seashell.

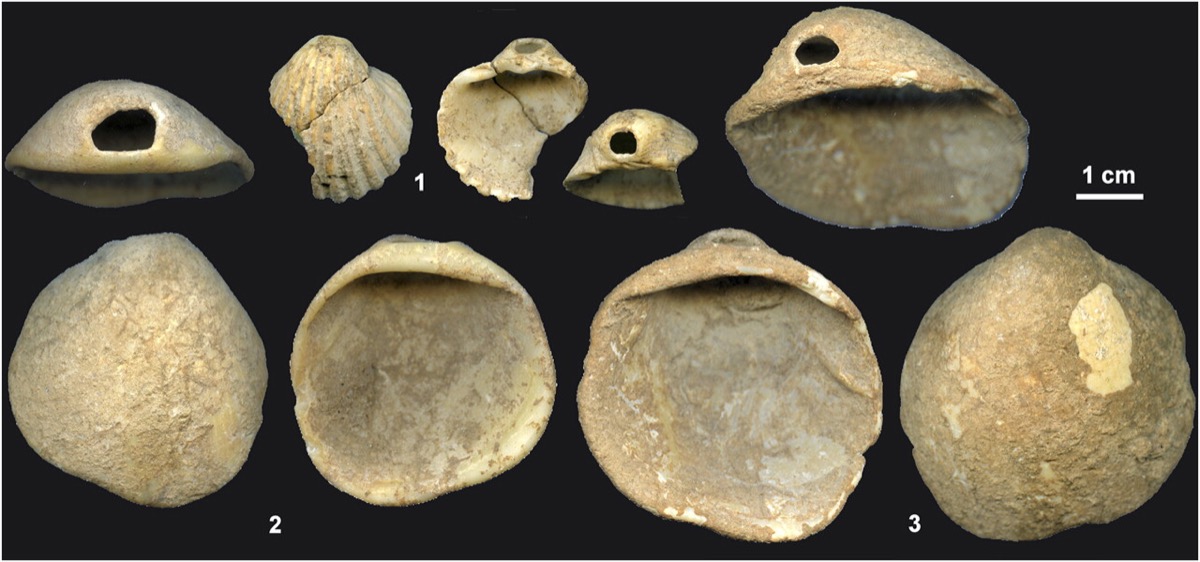

Among the polished whorls and sturdy half-shells washed ashore a couple miles from her cave, the Neanderthal girl knew precisely what she was looking for: cockle shells of a certain size and shape—about an inch across, perfectly round, and with a natural hole in the top.

She was picky about the hole, too. She collected those shells with eyelets she deemed best for threading. Her appreciation for seashells beyond food, and her imagination to string them together for a necklace or some other intention, would help scientists overturn nearly two centuries of assumptions and poorly conceived science that Neanderthals were dim-witted brutes.

The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Oceans

The cockle shells gathered in Neanderthal times were discovered fused into the maw of a sea cave overlooking Spain’s Cartagena Harbor. Several other shells found in the cave from the same era had been harvested live, for eating. Archaeologists could tell from their unblemished contours that they’d never bumped along the rocky shore.

The cockles had tumbled onto the beach empty. Someone collected them intentionally, but not for food. One keeper seashell, from a bittersweet clam, had been painted red. Another, from a thorny oyster, had a long second life as a cosmetic case. It still held a reddish pigment hand-ground from bits of hematite, pyrite, and other minerals, none found naturally in the cave.

These eons later, the powder still sparkles. And the girl’s human cousins are still picking up seashells.

When I read about the Neanderthal shell cache, I wondered whether the collector could have been a child. I imagined a young girl about five. That was my daughter’s age when, during a beach weekend on the east coast of Florida, she became obsessed with collecting only those shells with perfect holes in the top, for stringing necklaces and driftwood mobiles.

Those were the Bead Years in our house. In precisely ordered tackle boxes, she amassed colored beads and clear beads, owl beads and Scottie-dog beads, alphabet beads to spell out her friends’ names and I♥u. Now, as we slowly walked a bank of shell and seaweed sculpted by the high tide, that same collector’s gene was switched on at the Atlantic Ocean. Her fixated silence amplified the breaking waves beside us, the scold of gulls above, and the clink, clank, clatter of shells into her purple sand bucket. She skipped the shining olive shells, shark’s eyes, and other coiled prizes pressed into the wet sand. Like our ancestor, Ilana chose rounded half-shells: orange Atlantic cockles, purple-striped calico scallops, and scads of pendant-sized surf clams with hard-candy stripes and colors, all with a little round hole in the top.

When she’d chosen all she wanted, she wrote her name in big letters in the sand, along with the name of our town a couple hours inland, as if signing a seashell invoice from King Neptune.

Ten years later, those shells are still stashed here in our landlocked town, in a heavy little bag pushed to the back of a cabinet in my study. They’ve been tucked there since I rescued them from a pile of household detritus my husband was about to toss for spring cleaning. The shell necklaces and mobiles we strung on fishing line are long broken and thrown away. But I couldn’t bring myself to toss seashells so carefully chosen by the hands of a kindergartner, especially now that she’s a teenager keeping us at arm’s length.

I know of lots of other shell stashes, and inherited one. My mother-in-law once gave me a hand-painted porcelain cup from her late mother’s china cabinet. The delicate legacy was not the porcelain, but the two dozen jingle shells inside, shimmering pale yellow and orange. My husband’s grandmother had collected the translucent “mermaid’s toenails” with her young daughters along the beach at Long Island’s Peconic Bay. She stashed the memory in the small cup. Seventy years later, the shells still tinkle when I sift my fingers through their diaphanous forms. Finer than the porcelain, they are an order of magnitude stronger.

From the shell cults of prehistory to the impressive number of mollusk-inspired Pokémon characters, no creatures have stirred human admiration for as long or as intimately.

I wonder how many small but weighty bags and boxes of seashells are similarly hoarded in cabinets and closets from Muskegon to Mumbai; near the sea and many miles from it. Amid all the natural wonders cumulated at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, a small Money Cowrie, a Monetaria moneta not acquired by the founding father, is for me the most compelling. The humble cowrie was discovered in a subfloor pit beneath a slave house. A hole in the back of the shell and two grooves rubbed by a thread that had once run through it are part of the evidence that an enslaved African likely brought it to Virginia. The shell might have been attached to clothing, or somehow survived as a necklace.

It might have been a person’s secret stash; a connection to home.

A shell too is a home, and the life’s work of the animal that secretes it layer by layer with minerals from the surrounding environment. Consider the mollusks; soft animals far better known for the shells they build than for the lives within. The second-largest group of animals behind the arthropods that include insects, mollusks are everywhere—from the hundreds of snail species high in the Himalayas to the bone-white clams clustered at Earth’s greatest depths, filtering hydrothermal vents at Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean.

Seashells are the work of marine mollusks, the most diverse group of animals in the oceans. They inhabit worlds tiny—spiraled Ammoni-cera washing up on beaches around the globe with exquisite stripes too small to admire; and worlds vast—Tridacna gigas, or giant clams, weighing hundreds of pounds and glowing with millions of microalgae.

Seashells were money before coin, jewelry before gems, art before canvas.

Marine mollusks settle on reefs and rocks and seagrasses and sandy beaches and mudflats and countless places above and below. The violet sea snail Janthina janthina lives only on tropical surface waters, a molluscan Huck Finn floating on its own bubble raft. If anything happens to its homemade boat, the purple-shelled Huck will sink and die. Thin-spindled Tibia fusus hunkers deep in the sand thanks to its siphon that draws water for respiration through a long, thin shell canal like a hypodermic needle from a vial. The carrier snails, Xenophoridae, cement other shells, bits of coral, and even little pebbles onto their own shells in elaborate camouflage.

Marine mollusks are vegetarians and cannibals, fish hunters and filter feeders, algae distillers, and carrion eaters. They are sedentary blobs that leap and swim. Shy beings that create the showiest architecture of all time. Squishy invertebrates that make some of the hardest building materials known. Vulnerable species with the longest evolutionary history of any living today.

From the shell cults of prehistory to the impressive number of mollusk-inspired Pokémon characters, no creatures have stirred human admiration for as long or as intimately. Yet even in our time of Extinction Rebellion in the streets, and images of endangered species projected 1,250 feet up the side of the Empire State Building, the mollusks remain almost wholly anonymous artists.

Earth’s great shell middens—mounds of oyster, whelk, and other shells piled high along the world’s coastlines—testify to their significance as food since at least the early Stone Age. Raw or roasted, mollusks have often satisfied our appetites. Their iron, zinc, and other brain-boosting nutrients may have helped evolve the bigger brains that made us human.

But it is their shells that have captured our imaginations. Seashells were money before coin, jewelry before gems, art before canvas. Fossilized mussel shells found on the banks of the Solo River in Java, Indonesia, site of “Java Man,” bear geometric zigzags engraved half a million years ago by a purposeful hand. The decorated shells represent cognition among our human predecessors Homo erectus, and some of the world’s oldest-known art.

Seashells are the earliest-known keepsakes tucked into graves. A small cone shell, Conus ebraeus, holds its rose-colored tint after 75,000 years interred. The stubby cone was unearthed from the grave of a four-to-six-month-old infant in a large rock shelter in South Africa known as Border Cave. It had been notched by hand, strung onto a pendant, and worn for many years before being placed with the Stone Age baby.

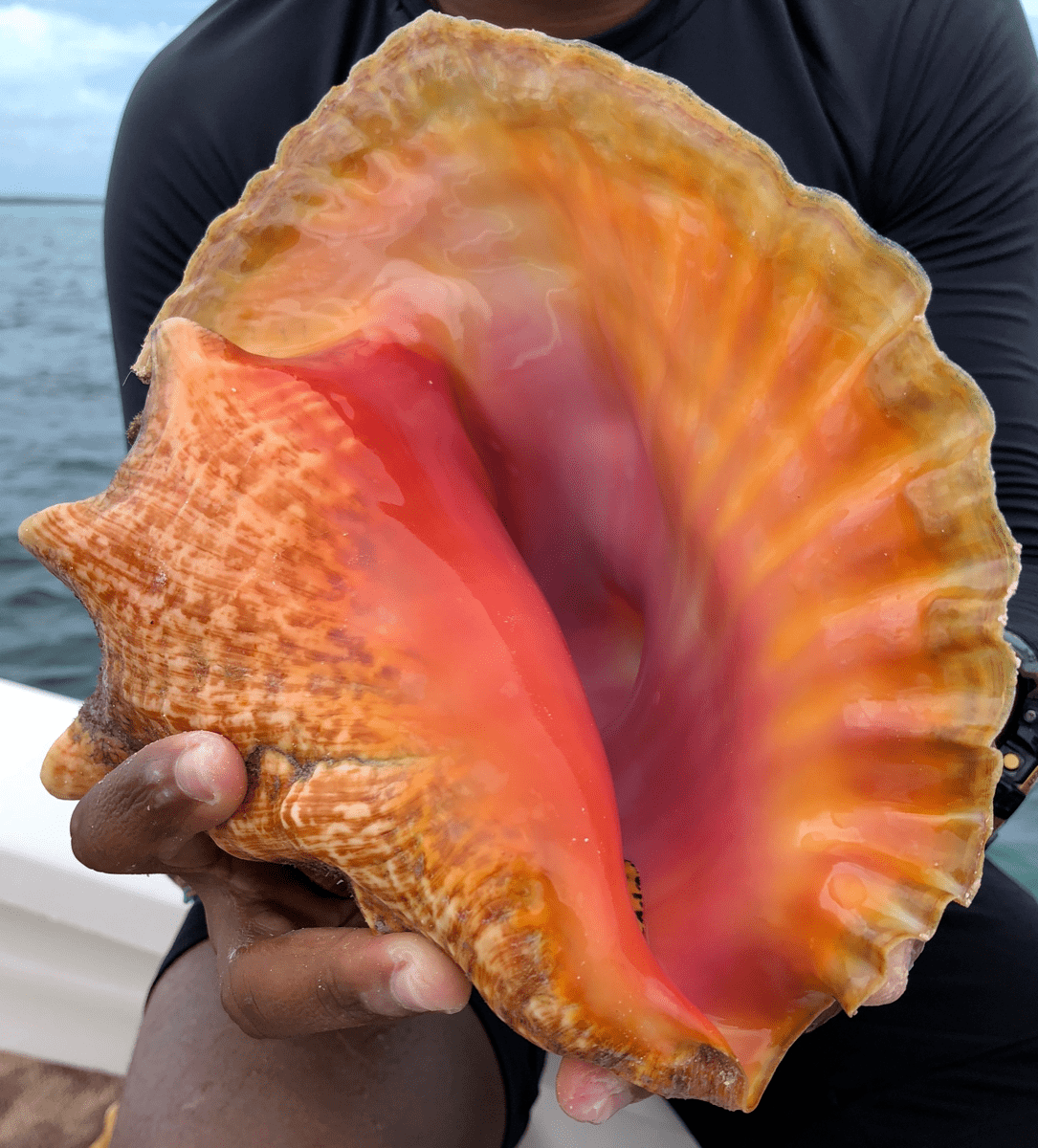

Shells are the most-collected naturalia along with rocks; easier to amass than butterflies and more affordable than gemstones. They are collected by children and by kings. A shell collection was unearthed from the ruins of Pompeii. Their devoted aficionados, known as conchologists, admit to a certain madness. But the polished forms captivate even casual admirers strolling the beach or museum displays: The perfect symmetry of a Chambered Nautilus. The pink-glossed lip of a Queen Conch. The pearlescent inlay of an abalone. The exceptional spines of a murex—raptor talons in some species, delicate doll combs in others. The distant roil in a trumpet shell, held to the ear for wisdom from the sea.

We’ve always tried to listen to shells. It’s striking how often they’ve led us to clear truths in murky times. Shells of unfamiliar species like ammonites provided evidence of evolution and extinction in an era of loyal belief that God made all creatures at once in everlasting perfection. Seashells on mountaintops told a story of shifting continents and rising and falling seas, articulating an Earth history much older than the six thousand years in the Bible. Layered in canyon walls and cliffsides and strata belowground, marine shells recorded a fossil diary for half a billion years, leaving one of Earth’s most complete archives of past life and global change.

Just as they hold Earth’s memory in mountains, or a mother’s memory in a small cup, seashells are more accurate recorders of human history than the humans who got to write it down. Shell middens once rose in North America like temples in the ancient world. Some early scientists and historians considered them mere garbage heaps of nomadic people. But the shells—contoured by long-ago hands to gird homes, sanctuaries, and public buildings, or buried in ancient cemeteries and shellwork factories—establish major pre-Columbian cities on U.S. soil. The “great cities of shell” make clear that the New World was hardly new, much less settled by bearded men from sailing ships. Around the world, shells are correcting history, fact-checking vanquishers.

The Portuguese archaeologist João Zilhão has spent his career tunneling deep into rock shelters and caves to understand how Neanderthals lived. Interpreting their marine shells from caves along Spain’s Iberian Peninsula has helped him shed light on Neanderthals’ intelligence, no less their humanity. The cockles join several tantalizing shell discoveries in proving that notions of symbolism and beauty long predate anatomically modern humans.

As early people interacted with greater numbers of outsiders, a cockle-shell necklace or other shell pendant might have been a way to burnish individual identity or declare allegiance to a social group. Coastal dwellers naturally adorned themselves with marine animals. Farther inland, the adornments were eagle claws or mammal teeth. Once trade networks took off, the transcendent appeal of shells carried them far from their ocean homes. Different species of the spiny oyster or Spondylus, the wild-spiked, blood-red bivalve that held the sparkly Neanderthal powder, are found in Neolithic burial sites across Europe as well as the rituals and jewelry of pre-Columbian cultures in South America, where they made their way from the depths of the Pacific Ocean to the tops of the Andes.

I asked Zilhão whether the cockle shells hidden in the Neanderthal sea cave could have been collected by a child. He didn’t hesitate. “Children and adolescents are more open to discovery,” he said. “One might guess that this use for an important social purpose was originally prompted by child’s play; a collection that begins while a child is helping out fishing or shell fishing on the coast, and running along and picking up these beautiful objects.

“There is something fundamental about shells’ aesthetics that pleases the brain, that must be very powerful. This is not just symbolic thinking. It’s this very modern sense of what is beautiful.”

One muggy June night at a ballroom seashell auction in Captiva, Florida, the barrier island where Anne Morrow Lindbergh wrote Gift from the Sea, her beloved 1955 book of shell wisdom, I watched two collectors try to outbid one another for a scarlet Spondylus crassisquama. Its two halves still attached at the hinge, the shell was big and round as a baseball and covered with at least a hundred curved spines, jutting short and long like a protozoan pincushion.

I appreciated those two modern women hungry for a species once revered by the Indigenous people of the Andes as the food of Pachamama, a fertility goddess who was also considered Earth’s mother. Bidding started at $50 and went up in discreet $25 waves of cardboard auction paddles to a final price of $250.

It wasn’t close to the highest price of the night for a single shell. A man named Donald Dan paid $2,000 for a rare slit shell, its conical steppes built by a secretive deep-sea mollusk named Entemnotrochus adansonianus bermudensis. Dan, a well-known shell dealer in Florida, grew up in the Philippines, where his boyhood acumen for seashells got him invited to shell club meetings at the presidential palace in Manila. Dan has helped the police solve the theft of rare shells from the American Museum of Natural History. He has helped scientists identify numerous species. They have named at least eight new species in his honor.

We’ve always tried to listen to shells. It’s striking how often they’ve led us to clear truths in murky times.

Among perils facing the sea, shell collecters’ harm to mollusks might compare to personal car trips versus the global fossil fuels industry in accruing the carbon emissions warming Earth. How you drive your car matters because transportation is the biggest source of U.S. emissions; our individual actions reflect the larger ethos that could help us live within the planet’s ecological limits. Yet one family’s way of living means little if we don’t change the larger industrial systems now breaking those limits.

The disappearance of mollusks and their shells from bays, beaches, and estuaries is most often linked to destruction of their habitats, including pollution. Mollusks famously clean up the water around them; scientists sometimes call them “the liver of our rivers.” Like livers, their soft bodies can take only so much. The digestive glands of marine mollusks living near human shores brim with dozens of contaminants such as PCBs and pesticides including DDT banned in the United States in 1972, revealing how everything we put out into the world comes back to us. Plastic is spreading yet farther. Tropical islands where no humans live are stifled in grocery-bag sludge thick as seaweed. Mollusks hunkered in the most remote arctic and deepest seas are ingesting microplastic fibers shed from our yoga pants.

Meanwhile the shell-makers most beloved to humans for their beauty—like Queen Conchs and Chambered Nautilus—are the ones we’re killing off for their beauty. Other threatened species are not listed as such, or studied as much, because mollusks don’t draw the attention or research dollars of animals like sea turtles and pandas whose eyes are big, soulful, and not mounted on tentacles. The Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature—the official gauge for the staggering decline of animals now underway around the world—severely underestimates loss of invertebrates, which make up an estimated 97 percent of all creatures.

The pages of history fill in some of what’s been lost. Early American coastlines were dense in oysters, scallops, clams—add abalone on the west coast—before we dredged or buried them alive to make way for waterfront development. When Henry Hudson sailed his ship Half Moon into New York Harbor in 1609, he had to navigate 350 square miles of oyster reefs. Within three centuries, oysters no longer colonized the harbor.

Colorful giant clams grew so abundantly in the shallow coasts of the Indo-Pacific that the nineteenth-century British conchologist Hugh Cuming described drifting over a solid mile of them on a collecting trip. Today the largest species are locally extinct in China, Taiwan, Singapore, and numerous smaller islands where they were overharvested for their adductor muscle—a sashimi delicacy—and their shells.

Ambitious restoration projects are underway in New York and other historic oyster bays around the world, and in giant-clam nurseries—some at top-secret locations to evade poachers—in the Pacific. Bringing back these seminal creatures could help restore the seas we share and establish the clean ocean farming we need to feed people and save wild fish. Yet their vulnerability to the warming, acidifying seas makes success far from certain.

The carbon dioxide we send into the atmosphere by burning coal and oil; manufacturing cement and plastics; and leveling the world’s great forests is warming the Earth unevenly. The sea and its life are taking a far greater blow than those of us on land. The oceans have silently absorbed 90 percent of the additional heat—already, some places have become too warm for mollusks. Oceans have also taken up a third of the carbon dioxide, which has made seawater 30 percent more acidic than at the start of the industrial era.

This chemical change, known as ocean acidification, has begun to limit the carbonate that mollusks use to make their shells. Acidic waters are also boring into some shells, pitting or eroding them. One of the world’s tiniest shelled creatures, the sea butterflies—a source of food for other sea life including shorebirds and whales—have thin, hard shells especially sensitive to the changing ocean chemistry. Scientists around the world have found these pteropod shells thinning, or corroding in their delicate outer layers.

The luminous fairies may be signaling what could happen to other shelled life as the seas turn more acidic. In the Pacific Northwest, young oysters have died off en masse, unable to build shell in lower-pH seawater. In California, scientists detect radical changes in the way mussels build their sleek black shells, trying to adapt. In the lab, ubiquitous periwinkles—wee bivalves common to rocky shores and soup bowls—build a weaker shell when subjected to seawater just a bit more acidic than today’s. In experiments that replicate the acidity forecast for a century from now, conch shells deteriorate. Scallops and clams build thinner homes. Scientists find that triton shells living near seeps with predicted future levels of CO2 grow thinner—and a third smaller—than those in normal conditions. The large spirals blown by the Greek god Triton to calm the seas or raise the waves are sending us a signal.

In William Wordsworth’s autobiographical poem The Prelude, the narrator falls asleep near the sea and starts to dream. He holds a seashell to his ear and hears

A loud prophetic blast of harmony;

An Ode, in passion uttered, which foretold

Destruction to the children of the earth

By deluge, now at hand.

Seashells do not really echo their native ocean, as people have believed for centuries. Nor do they foretell coming storms, as old superstition had it. Contrary to a more modern theory still found in some kids’ fact books, they don’t magnify the sound of blood through our veins.

No, the poet got much closer to the science when his narrator held the shell to his ear and heard his own mind’s fear. A large spiraled shell like a conch, whelk, or India’s sacred chank is simply the perfect resonating chamber. Like a hand cupped to the ear, it picks up ambient noise in the environment—amplifying exactly what’s going on around us.

The modern signs from seashells are as clear as those that showed earlier generations the age of Earth or the rise and fall of ancient seas. They are also pointing to the considerable solutions that lie beneath the ocean’s waves. The mollusks, and the seagrass meadows where many of them begin life, sequester tons of carbon. They build some of the world’s most efficient homes, and the best storm barriers known. They tap sunlight and algae for fuel.

Like a hand cupped to the ear, it picks up ambient noise in the environment—amplifying exactly what’s going on around us.

Their ranks include the longest-lived animal known—the burrowing Ocean Quahog, Arctica islandica, that can live beyond four hundred years—and the longest-surviving. The fabled nautilus has lived through warming, acidic oceans before. They do hold wisdom from the sea.

This book was born in a record warm and rainy winter (records now shattered) on Sanibel Island in southwest Florida, where every street is named for the seashells that wash ashore on the southern beaches. The marine biologist José H. Leal had invited me to give a book talk at Sanibel’s Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum, which is devoted entirely to shells and their makers. Leal, who grew up near the beach in Rio de Janeiro, has the lithe build, leather bracelets, and serene bearing of a lifelong surfer. He is an expert in the biodiversity of mollusks and in their constantly changing scientific nomenclature. Fluent in four languages, he reads another two. He has worked in the world’s great shell collections, from the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, and edits The Nautilus, one of the oldest scientific journals of mollusks. Yet he found what he considers his most vital role in a place that hosts shell-craft lessons where visitors glue googly eyes onto nature’s masterworks. For Leal, and a number of marine scientists I’ve met in the years since, helping people understand what’s happening to the world and its life has become even more important than their research. (I once asked Leal for his opinion on shell craft; he would say only that some of his best friends glue googly eyes on shells.)

Ten years before I met Leal, the shell museum had surveyed its visitors, many of them tourists and their children visiting Florida, to find out how much they already knew about seashells. The survey revealed that 90 percent of the visitors had no idea that a shell is made by a living animal. Most people thought they were stones.

As much as the modern crisis of truth is a conceit of politics, it is also a consequence of that severing from nature. When Pokémon characters are more familiar to children than the snails that helped inspire them, when drifts of plastic are far more common than seashells on many beaches of the world, natural history and life’s struggle to survive are hard to know.

Excerpted from The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Oceans. Copyright © 2021 by Cynthia Barnett. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.Donate To Science Friday

Cynthia Barnett is an environmental journalist in residence at the University of Florida, and author of The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Oceans (WW Norton, 2021). She’s based in Gainesville, Florida.