Unpacking The Demand For Multilingual Science Media

Audiences tell us how they engage with and share science stories in multiple languages.

SciFri Findings is a series that explores new practices in journalism and science communication, and their impact on our audiences. Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest reports!

If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that science literacy—and in particular, language barriers in the sciences—can have a huge effect on people’s everyday lives. Miscommunications and accessibility issues can become big problems; with COVID-19, for example, the lack of multilingual public health information has caused dire circumstances for communities who don’t speak English.

The lack of linguistic accessibility has troubled the sciences for decades, and as a result, hindered diversity and impacted science literacy.

During the pandemic, increasing the visibility of local experts and inviting them to communicate research in their own language is important for building community trust. Effective public health interventions are based on local knowledge and expertise. In 2015, The Atlantic reported that 80% of scientific papers were written in English, leaving millions of scientists and researchers around the world in the dark on the latest innovations and findings in their fields. These linguistic barriers can result in non-English speakers being underrepresented in STEM fields. Limiting the languages that research is communicated has also encouraged “parachute science” in developing countries—when research within a country is conducted almost exclusively by foreign scientists.

Those are some of the reasons Science Friday has been examining its past and current efforts to deliver Spanish-language content. As a public media and non-profit organization, we produce science journalism in English via a radio program, website, and YouTube channel. We have, however, pursued opportunities to create stories in other languages, in particular Spanish. Science Friday’s first effort to offer programming in another language was in 1994, when we worked with Hispanic Radio Network to produce stories in Spanish. Since then, we have experimented with ways to help make science more accessible in Spanish, including:

Our most recent Spanish-language story in August 2020 provided a chance to learn more about our audience’s interest in multilingual science content. Led by radio intern Attabey Rodríguez Benítez, with the help of digital producer Lauren Young, we planned and produced Spanish and English language content in parallel, creating a podcast episode and digital article in both Spanish and English.

We aired an interview between our host Ira Flatow and biochemist Rosa Vásquez Espinoza in English, discussing the microbes of Peru’s Boiling River, and how she collaborates with local communities to do her research. A digital article profiled Vásquez Espinoza and her work, written in English by Rodríguez Benítez. Following the broadcast, Rodríguez Benítez and producer Kathleen Davis put together an additional podcast interview and digital article with Vásquez Espinoza in Spanish. Alongside each article and podcast, we included a reciprocal link to the version of the article in the alternate language. (“This story is available in English. Esta historia está disponible en inglés.”)

As Science Friday’s Manager of Impact Strategy, I watched our producers fluttering translation copies rapidly back and forth on Slack. I wanted to better understand: How does our audience engage with multilingual content?

In the US, one in five Americans speaks a language other than English at home, with the highest percentage (13.4%) speaking Spanish. To better understand how our recent dual language content was received by our audience, I asked Science Friday’s podcast, radio, social, and newsletter audiences questions about why, where, and how frequently they use multilingual media and news.

Two hundred and thirty people responded, and 82% completed the survey. We were interested in how many of our audience members understood, spoke, or read another language as it would help us understand the demand for content in multiple languages. We found that 83% of respondents spoke, read, and/or understood a language other than English.

| Recruitment Avenues | Number Of Respondents From This Channel |

Percentage Of Total Respondents |

| 1 | 0.4 | |

| Podcast Extra | 31 | 13.5 |

| SciFri Website | 124 | 53.9 |

| 6 | 2.6 | |

| WNYC | 68 | 29.6 |

| Total | 230 | 100.0 |

Here is a breakdown of where respondents found our Translated Science Media Survey. N=230, 82% completion rate, 83% spoke/read/understood language outside of English.

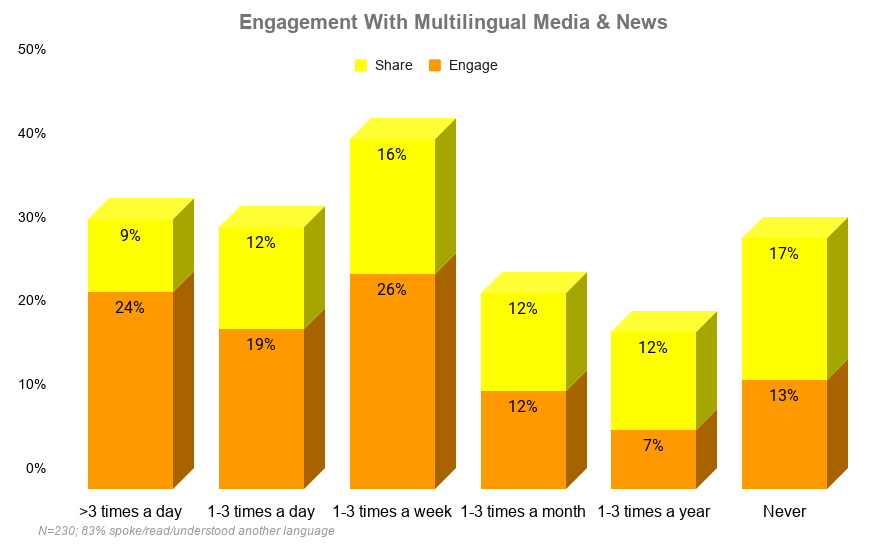

A high percentage of respondents (43%) engaged at least daily with multilingual media. However, when asked about sharing multilingual media, only 21% of respondents reported doing so daily (no data is available on how often they share English-language media daily). This led to more questions: Why do audiences engage with, but not share, multilingual content?

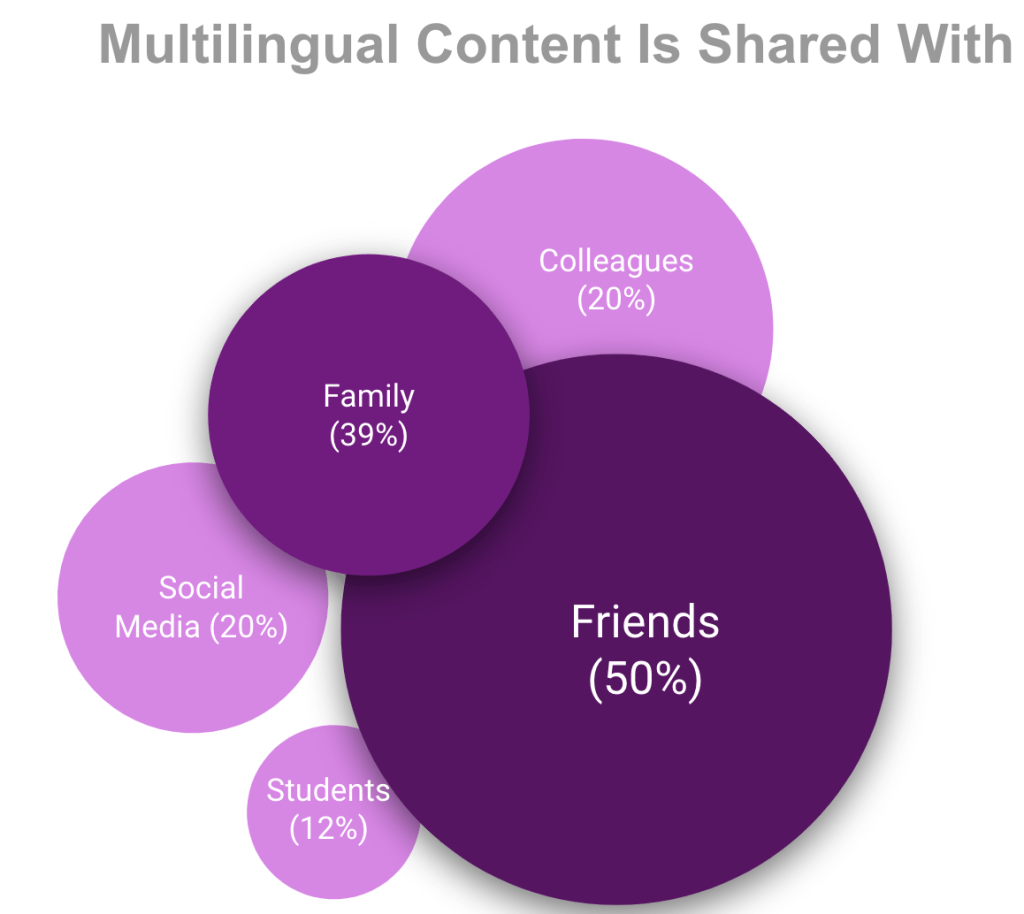

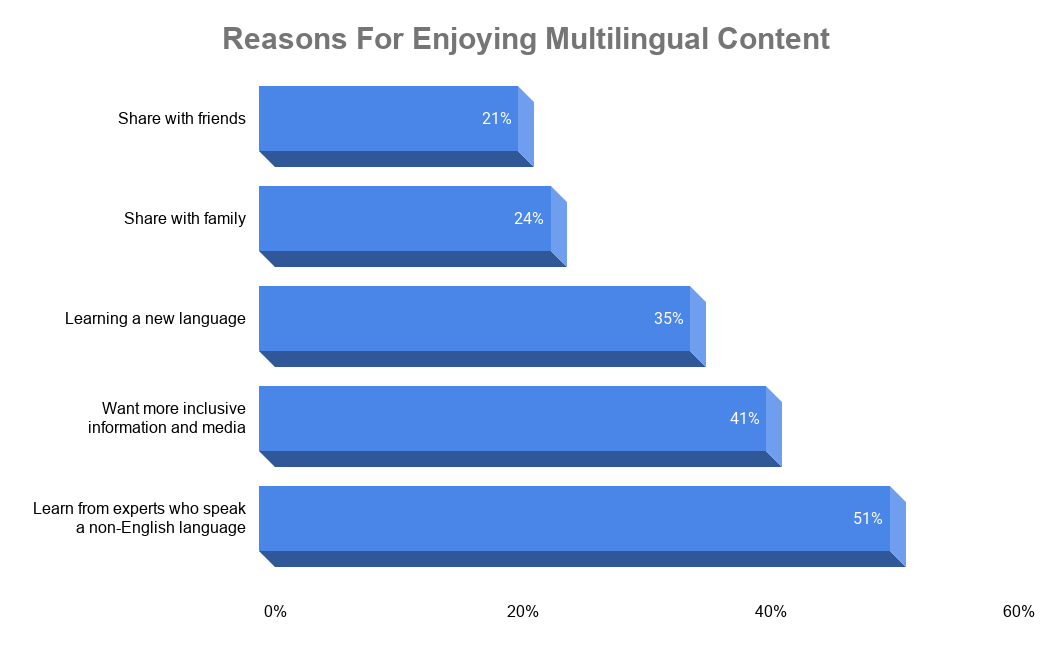

When we asked people why they engage with multilingual content, and with whom they share it, most respondents said they shared multilingual content with friends (50%) and family (39%). Reasons why users listen to or read content in other languages varied, but half of respondents said they engaged with content because they wanted to learn from experts who speak languages they speak.

Fifty-one percent of participants wanted to learn from local experts (“often get different perspective[s] in native languages”), and 41% wanted more inclusive media (“Would be great to include voices from Indigenous communities in Indigenous languages”). These findings suggest that audiences engage with multimedia content that amplify local voices, and experts that reflect their communities.

Intentionality of program design is a key component in advancing science literacy. Connecting a producer and researcher who were both native Spanish speakers early in the production process of our recent podcast episode helped us establish early on what a Spanish-speaking audience would want to learn in relation to this story. This allowed us to document the nuances of the research in a way that was accessible, and better catered to native Spanish-speaking audience members.

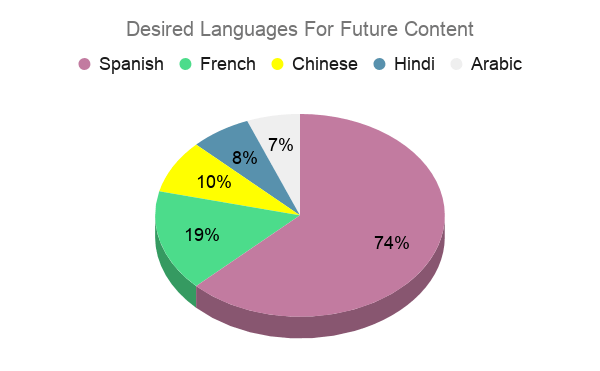

Creating Spanish-language content can also serve English-speaking audiences. Thirty-four percent of respondents engaged with multilingual content for language learning. The vast majority of respondents (74%) were interested in future content in Spanish, followed by French (19%), Chinese (10%), Hindi (8%), and Arabic (7%). Educators may consider utilizing Spanish science media in STEM and language learning curriculum.

Numbers are only part of the story. Because the Spanish-language version of the podcast episode was added to the Science Friday podcast feed, most subscribers received both versions automatically. While feedback was positive, respondents did express surprise and even frustration to hear a Spanish conversation in the Science Friday podcast feed. (“If you want multilingual podcasts, let the listeners choose what language; don’t make us download something we won’t understand in the feed. This is especially important for bandwidth limitations.”) This has made us consider how we might provide choice for audience members as we continue to consider multilingual stories.

The overwhelming majority of survey respondents were excited about Spanish content. They told us the reasons they desired Spanish content included non-English speakers’ desire to better understand science, and to see programming for historically underserved communities. Here are a few of the comments shared by survey respondents:

Creating multilingual stories requires intentional staffing, production, and distribution. As content creators, we recognize there is a need to balance science communication, storytelling, and audience voice in how we choose and produce stories. One of Rodríguez Benítez’s favorite moments while producing our recent segment was hearing that Vásquez Espinoza’s grandmother listened to the story—one of the few times she got to hear and understand her granddaughter’s work.

Multilingual content is a worthwhile effort that may lead to more equitable audience impact, and greater science learning and activation among new audiences. These stories can allow us to see science for what it truly is: a global community endeavor!

*Editor’s Note 5/24/2021: This page has been updated to add Aleszu Bajak’s contributions to SciFri en Español and corrected the date in which the programming began.

Nahima Ahmed was Science Friday’s Manager of Impact Strategy. She is a researcher who loves to cook curry, discuss identity, and helped the team understand how stories can shape audiences’ access to and interest in science.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.