Meet The Sago Pondweed, World Citizen

In “Dispersals,” the story of the sago pondweed helped the author imagine what it could mean to have roots that span continents.

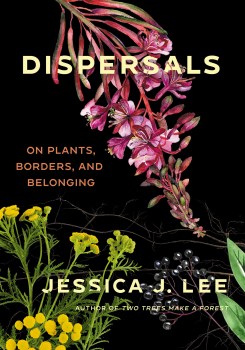

The following is an excerpt from Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging by Jessica J. Lee.

When you purchase products through the Bookshop.org link on this page, Science Friday earns a small commission which helps support our journalism.

Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging

Paddling from our camp in the corner of Brandenburg, we emerged from a narrow, tree-sheltered stream to a wider, more windswept lake. Small choppy waves rose here, nudging our canoes in rhythm as we cut our way westward. I’d paddled this lake plateau of Germany many times— swum it even more often—but still I was enlivened by the sights made possible by being in the middle of the water. Away from dry land, away from the roads and trails that only loosely strung themselves around this region. Water was a way of seeing more—at a different angle, below the land and roots of trees that forest east Germany. Here I could see freshwater life clearly. White and butter-yellow lilies bobbing in our gentle wake. Lotus seed heads plump and patterned with holes—these only ever sent my mind wandering to food, to chilli-flecked lotus root salads and sweet soups scattered with lotus seeds. Beneath us, sago pondweed danced like fennel fronds strung underwater. Every so often, my oar would bring up a strand of it and I’d twizzle its stems between my fingers. Jade green and delicate.

But I learned later that this plant was hardier than it appeared—as happy to grow in still lakes as it is in rivers, canals, ditches, and brackish lagoons. In turbid conditions, aquatic plants like sago pondweed help a body of water return to a period of relative clarity and health. In the late 1980s, when one of this region’s largest lakes began to recover from eutrophication, sago pondweed was one of the first species to slowly recolonise the lake and thrive, having survived even when the water was depleted of oxygen.

A map of sago pondweed’s native range shows nearly the entire planet; it lives on every continent except Antarctica. I look at the list of countries it calls home, a paragraph- size blot of places from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, and a purple highlight over Hawai‘i, the only place it is considered introduced. Sago pondweed’s range is therefore described as “cosmopolitan.”

What is it to be a world citizen amongst species? The sago pondweed lives under a banner of free movement in a world increasingly marked by borders. But the natural world presses against our tendency to lay arbitrary geopolitical boundaries upon it—and we, by our own movements, likewise transgress the borders we apply.

The first time I contemplated what it meant to be cosmopolitan, I was eighteen, clutching a pink pocket-size book by Jacques Derrida. To speak of the cosmopolitan, I read, requires us to speak of hospitality. A posture of welcome from those who stay in place.

For those who move, the realities of movement are far different. The first international standard for passports was not agreed upon until the 1920s, in the aftermath of the First World War. Efforts at plant quarantine, however, preceded it by decades. Measures to control the movement of plants across borders were widely enacted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with national legislation on pest control and quarantines coming into effect in Britain, the United States, Canada, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, amongst others, as knowledge of plant pests and the means of controlling them increased. But what of the world that does not fall tidily within these maps? Not all passports grant the same rights of passage. Some species—like the pondweed—might belong everywhere at once.

Though I move, just as my parents and grandparents have, I do not want to live afloat, at home anywhere I go. My friends are buying houses, asking which of my phone numbers is still valid and which they can delete. I am in movement nonetheless. Each time I move I find myself longing for a past place, unable to wash it from me. I am my mother’s daughter, seeking ponds in every place.

When I read of the sago pondweed’s recolonisation of that Berlin lake, I learn that it spread itself not by seed, but through tubers reaching beneath the lakebed, slow and persistent. What would it mean to move and stay rooted— to have roots that can span continents?

Excerpted from Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging, Copyright © 2024 by Jessica J. Lee, reprinted with permission of Catapult.

Jessica J. Lee is an environmental historian and the author of Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging. She’s based in Berlin, Germany.