The Real Scientific Revolution Behind ‘Frankenstein’

Mary Shelley’s classic novel was written in a world where the dead twitched.

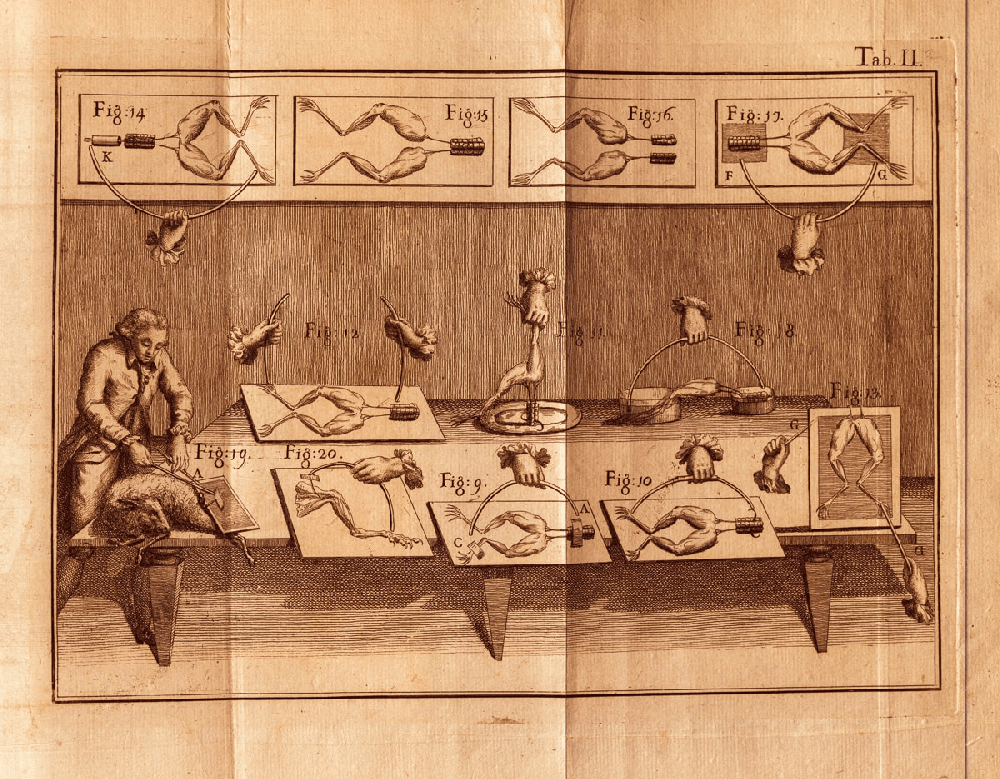

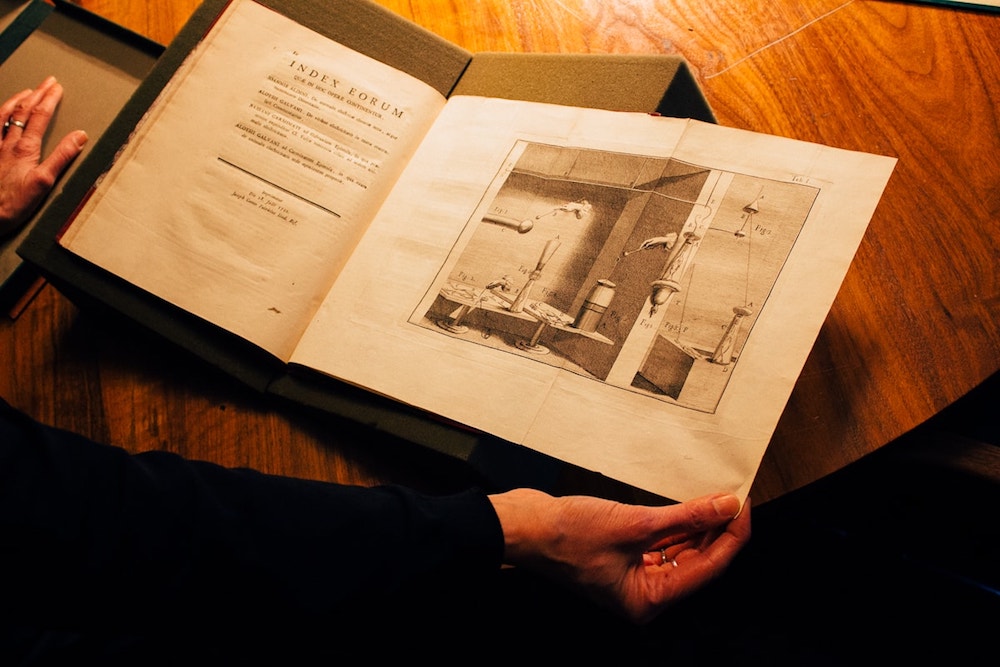

Italian scientist Luigi Galvani (left) and the steps of a suspended reanimation experiment on frog legs and a sheep. The manicules (pointing hands) illustrate to the reader how the steps should be performed. From “De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius” by Luigi Galvani, 1792. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library

This story is part of our winter Book Club conversation about Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or call our special voicemail at 567-243-2456.

It was an early September evening in 1786. An Italian physician and physicist, Luigi Galvani, lined frog specimens one by one along a parapet, each dangling by the spinal cord from a metal hook. Then by chance, one of the hooks touched an iron plate, and much to the scientist’s surprise, the frog’s legs began to mysteriously twitch—the dead animal seemingly reanimated with life.

“Behold! A variety of not infrequent spontaneous movements in the frog,” Galvani wrote later in 1792 in his book about his experiments.

Galvani had been conducting a series of experiments on muscular motion in dissected animals when he first observed the contractions and spasms of the frogs’ legs that were stimulated by an electric current. Although Galvani would describe it as “animal electricity,” the phenomenon would later be named “galvanism,” after him. He and others repeated and performed variations of his famous frog experiment and even applied electric stimulation to the human body, both dead and alive. Scientists began to wonder if Galvani had discovered an innate vital force that powered life.

Demystifying the workings of the human body and living organisms—distinguishing living from dead—was just one of the areas of research that swept across Europe during the Enlightenment, the period of scientific discovery from the late 1700s to the early 1800s. Chemists competed to identify new elements; physicians began to focus on pathological changes from disease; physicists studied the nature of electricity. It created the perfect setting for Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein, says Thomas Broman, a recently retired science historian specializing in the Enlightenment at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The literary movement Romanticism, “itself is a culture that fetishizes genius and the brilliance of young people making a new world,” Broman says. “So there’s such a huge buzz about the genius of scientists and I’m sure [Shelley] is playing on some of this idea, too.”

Shelley was no stranger to current research. She would listen to philosophical and scientific discussions among her circle of intellectual friends. She even journaled about attending a public lecture on the medicinal uses of electricity in London—one form of the many science shows for entertainment and education that was in vogue. Nowhere in the original Frankenstein does she mention the word “electricity,” however, she reveals in the introduction of her 1831 edition that the popular galvanism experiments were a potential impetus for bringing the creature to life.

“It’s very easy to imagine that these kinds of experiments were in her mind, that really informed the way she was thinking about creating artificial life,” says Paola Bertucci, an associate professor of history of medicine at Yale University.

The experiments of Shelley’s time laid down the necessary fundamental research for modern medicine and the technologies of Industrial Revolution, says Broman. Pathological anatomy helped reconceptualize the treatment of disease, while new ideas of atomic combinations led to deeper understandings of chemical compounds.

Galvani’s research and those famous twitching frog legs were the beginning of electricity as we know it, Bertucci explains. The popularity of electric experiments eventually gave way to Alessandro Volta’s invention of the voltaic pile—the early electric battery, she says. And despite being a centuries-years-old experiment, dissected frog legs still kick on laboratory tables—students in physiology labs perform iterations of the electrical experiments that likely influenced the world of Frankenstein.

To dive into the scientific world that Shelley lived in, Science Friday took a peek at the experiments tucked between the pages of late 18th- and early 19th-century texts at the rare book room of the New York Academy of Medicine in New York City with historical collections librarian Arlene Shaner. Books written by scientists like Galvani and his nephew Giovanni Aldini contain electric medical instruments, practices on how to revive the apparent dead, procedures of early skin grafting, and galvanic experiments on human corpses. The vivid and rather macabre depictions are easily reminiscent of Frankenstein.

Historical collections librarian Arlene Shaner. Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt

Table I from Luigi Galvani’s book depicting his various frog reanimation experiments. From “De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius” by Luigi Galvani, 1792. Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt

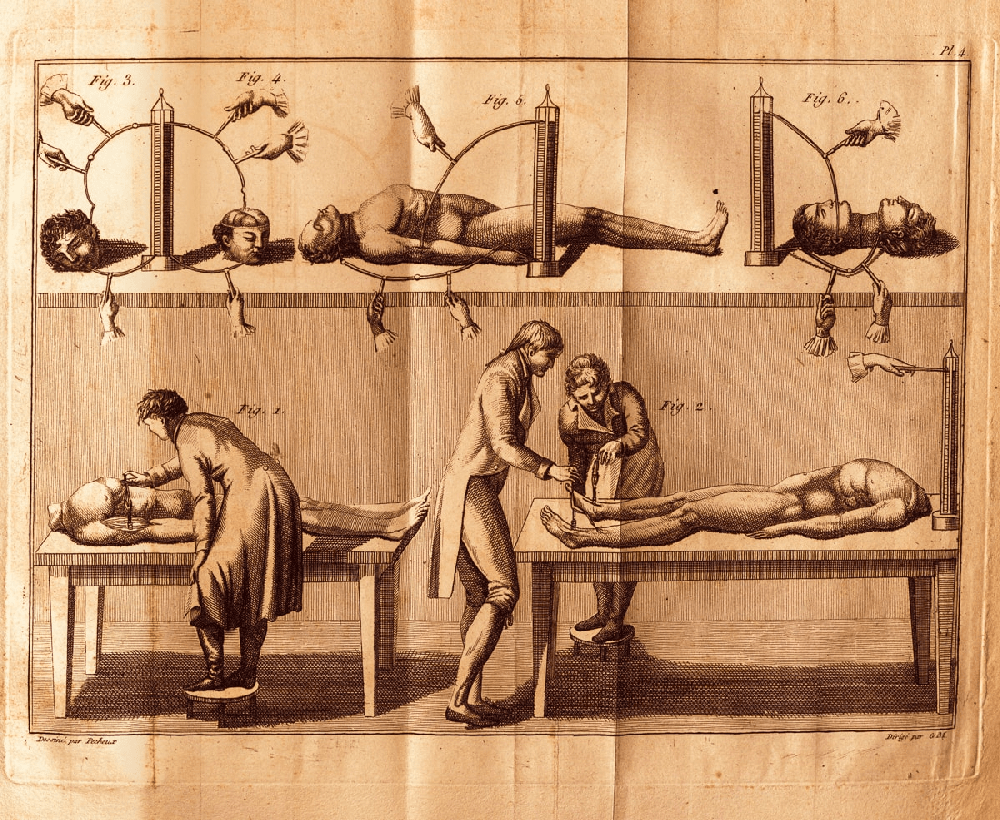

From “General views on the application of galvanism to medical purposes; principally in cases of suspended animation” by Giovanni Aldini, 1819. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library

After Galvani’s initial experiments on frogs, scientists took galvanism a step further—Galvani’s nephew, Italian physicist Giovanni Aldini, started sending electric stimuli into the bodies of dead humans.

Aldini noted, “various contractions, sometimes of the fingers, sometimes of the hand, and sometimes even of the whole arm. The fingers bend and unbend very visibly, and sometimes the whole fore-arm is carried towards the chest.”

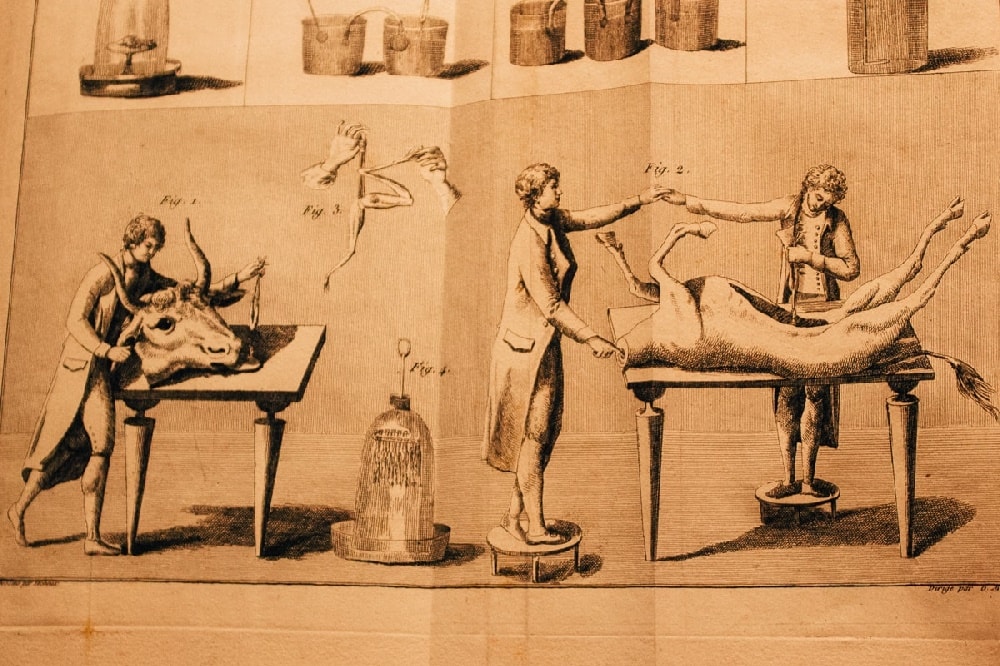

From “General views on the application of galvanism to medical purposes; principally in cases of suspended animation” by Giovanni Aldini, 1819. Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt

Aldini also conducted a variety of galvanic experiments on large bodied animals like oxen, as depicted above in his 1819 book.

“The size and vigour of the English oxen, generally so well marked, increased the effects of the galvanism,” Aldini writes about an 1803 experiment on an ox in London. “The irritation of the organs was so great, that the whole head was put into most violent agitation.”

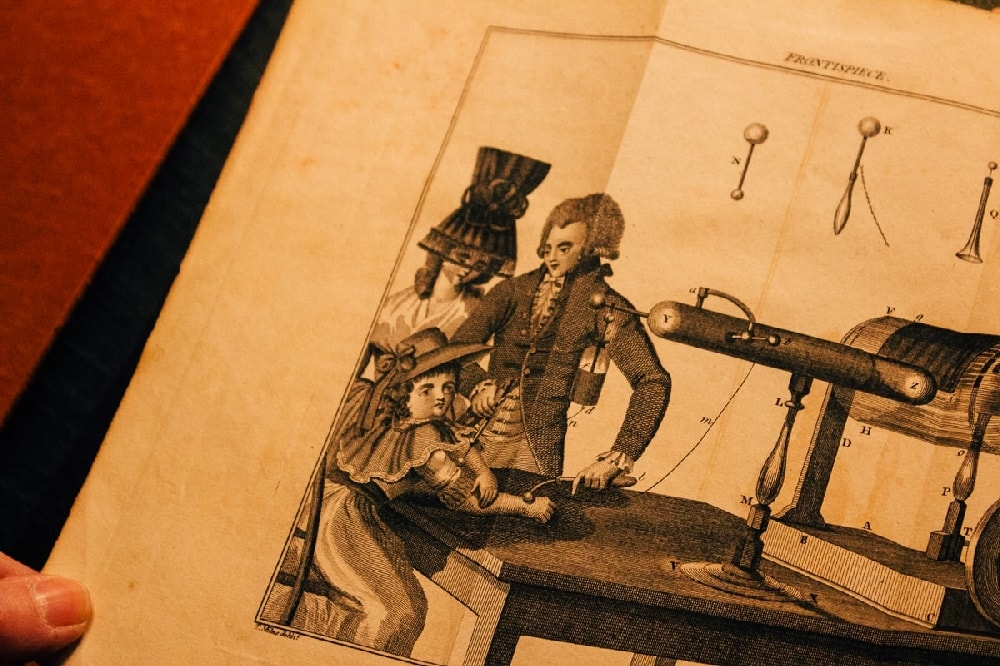

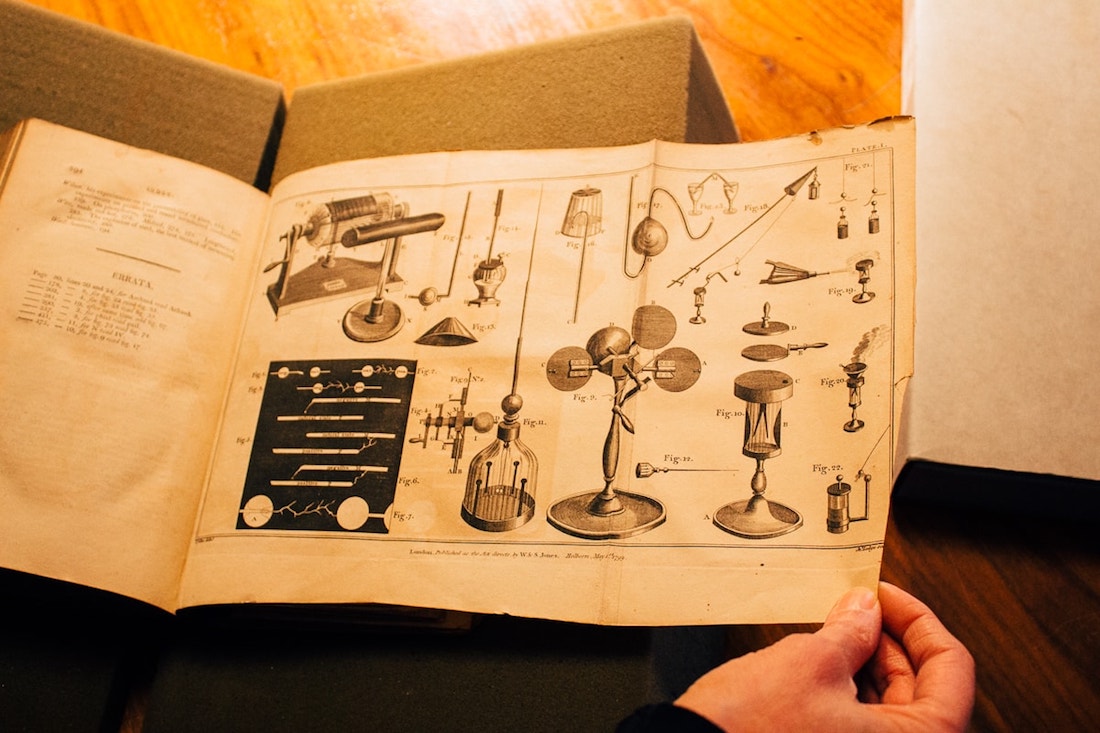

From “An Essay on Electricity, Explaining The Principles of that Useful Science; and Describing The Instruments” by George Adams, 1799. Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt.

Electricity was one of the hottest items of discussion throughout the 18th century. Scientists would hold public science shows and lectures at the Royal Society in London as a form of both entertainment and knowledge. “It was very fun for salons, parties, and tricks, and there were a lot of lecturers who would display very vivid phenomena of electricity,” says Thomas Broman. Often, a lecturer would make the hairs on a volunteer’s arm stand on end with electricity, he says. In the illustration above, a scientist demonstrates an electric experiment on a young girl.

From “An Essay on Electricity, Explaining The Principles of that Useful Science; and Describing The Instruments” by George Adams, 1799. Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt

Many medical texts often served dual purposes, containing both information on practices and treatments as well as a catalog of instruments for sale, explains Shaner. George Adam’s essays on electricity, for instance, includes various electrical instruments, from optical to chemical devices.

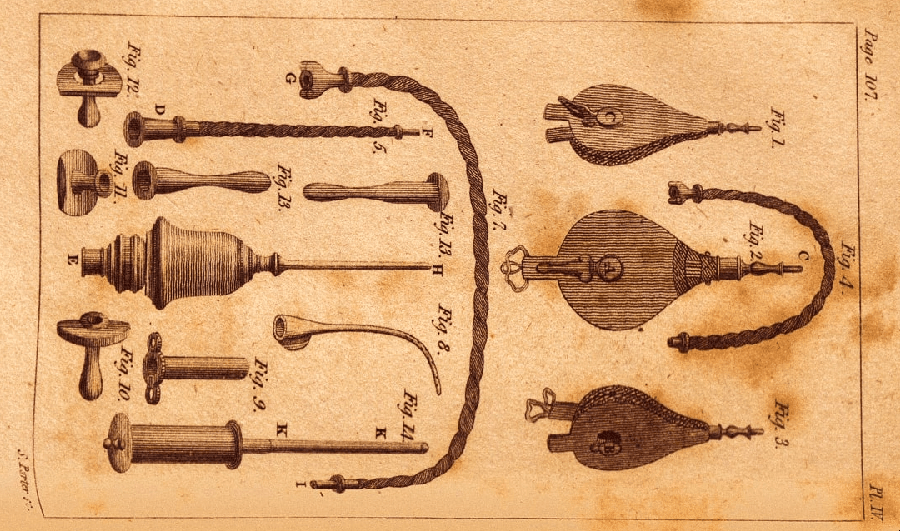

From “The accidents of human life : with hints for their prevention, or the removal of their consequences” by Newton Bosworth, 1813. Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine

In the same vein of searching for the force that powers life, scientists and society troubled over distinguishing states of life and death—especially in victims of drowning. Doctors published manuals on signs of human death, while societies popped up across Europe that disseminated information about how to resurrect those who drowned, such as the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned. A device such as the bellows and pipes depicted above were used for resuscitation.

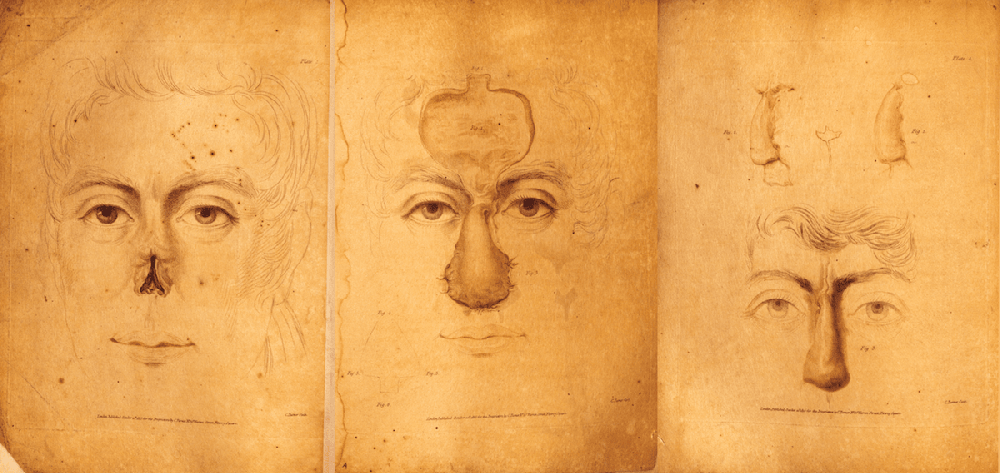

From “An account of two successful operations for restoring a lost nose from the integuments of the forehead, in the cases of two officers of His Majesty's Army; to which are prefixed, historical and physiological remarks on the nasal operation; including descriptions of the Indian and Italian methods” by J.C. Carpue, 1816. Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine

The illustrations above shows a kind of skin grafting, reconstruction procedure of a soldier who had lost his nose. Performed by English surgeon J.C. Carpue, skin from the forehead is sliced and turned down over the nose to restore the lost tissue. The three pages show the different steps and healing process of the operation.

A surgical medical kit from the 19th century. Some of the tools are actually similar to what might be found in today’s surgical rooms, says Arlene Shaner. Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt

In human anatomy, “more and more specific knowledge of the body’s structure was really beginning to inform the way that people were thinking of causes of disease,” says Thomas Broman. Doctors took notice to the “different pathological changes that the body could undergo when falling ill.” These ideas propelled modern medicine forward.

Credit: Daniel Peterschmidt

Special thanks to Arlene Shaner and the New York Academy of Medicine.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.