Pixel Art Conjures Nostalgia For A Screen Experience That Didn’t Exist

Crisply pixelated video games evoke nostalgia for decades past. But early games, played on boxy CRT televisions, just didn’t look like that.

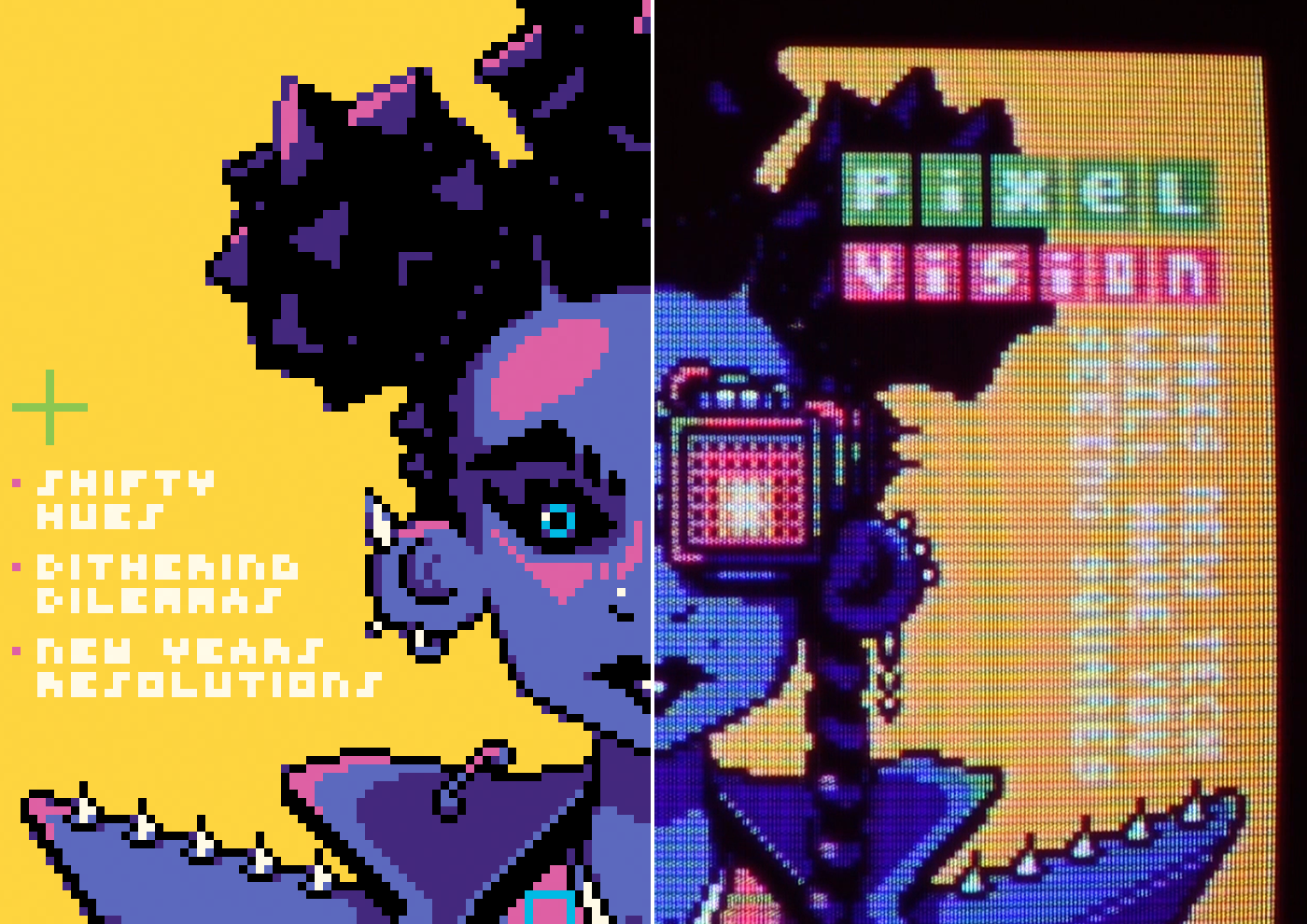

Left: Pixel art on a modern screen. Right: Pixel art on a CRT display. Illustration by Brandon James Greer

Pixel art has experienced a revival. In this type of digital illustration, reminiscent of early video games, images are pieced together mosaic-style using tiny blocks of color. Popular games like Stardew Valley feature sharp pixels, stair-stepping lines, and high-contrast colors, seeming to recapture the charm of old favorites.

Pixel art has experienced a revival. In this type of digital illustration, reminiscent of early video games, images are pieced together mosaic-style using tiny blocks of color. Popular games like Stardew Valley feature sharp pixels, stair-stepping lines, and high-contrast colors, seeming to recapture the charm of old favorites.

But modern pixel art is a curious example of how changes in technology blur our understanding of the past: Old console games never looked like that.

When digital artist Brandon Greer dug up an old Super Nintendo console and plugged it into his flatscreen TV, his heart sank. His favorite games looked more cartoonish, less fluid and lifelike. But his disappointment wasn’t just because Greer had lost the rose-colored glasses of childhood. Even though modern screens are objectively better now than they were in the 1990s, the game looked worse.

Dr. David Long, a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology who’s researched digital display systems for decades, says the discrepancy comes down to how TVs produce light and color. Cathode ray tube, or CRT, televisions—the big, boxy ones that Gen Z may not remember—were the only game in town before the flatscreen revolution in the early 2000s brought us crisp imaging on plasma, LED, LCD, and OLED displays. Back then, in the days of analog television, “you would never use the term ‘pixel.’ It didn’t exist,” Long says. “Instead, the patterns were formed by cathode ray tube physics.”

The inside surface of a CRT screen is coated with tiny clusters of phosphors, “materials that can provide a lingering light glow when excited by energy,” Long explains. Each cluster contains three colors of phosphors: red, blue, and green. At the back of the TV, three electron guns—one for each color—zaps each trio of phosphors in rapid succession, scanning from left to right, top to bottom, like a typewriter. As phosphors are excited, they emit their designated color.

Whereas in modern LCD displays the light emitted by each pixel effectively stays in its lane, the firefly glow from a CRT’s phosphor coating bleeds into the light created by its neighbors. The final image is a painterly blend with soft edges—no sharp corners or harsh bands of contrasting colors.

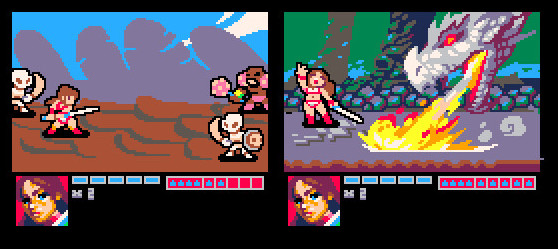

Clever game designers of yore were able to take the idiosyncrasies and limitations of the CRT displays and turn them to their advantage, according to modern pixel artist and indie game designer Christina-Antoinette Neofotistou. (Neofotistou currently works for Minecraft, the world-building game with the chunkiest 3D pixels of all.)

“Some of the tricks you could do because of the blurriness…of the CRT display are not doable [on a flatscreen]. You can’t see them anymore in the modern displays,” Neofotistou says. A prime example is “dithering,” which uses a checkerboard pattern of two colors to create a third intermediate color, as well as some impressive effects like the illusion of transparency.

Even so, Neofotistou says she prefers the clean aesthetic of modern pixel art—it’s more consistent and predictable. From a designer’s perspective, “all the complex, and flawed, interplay of photons and cathode rays and blended colors [of a CRT] isn’t part of the creation process, it’s an afterthought,” she explains.

Others like Greer, a professional pixel artist who shares tutorials and timelapses of his work with more than 200,000 YouTube subscribers, find beauty in the CRT chaos. At the end of each video, he displays his latest sprite or scene on an old CRT. “I generally think of it as degrading the image—like dirtying it up in a way that I think has a kind of charm to it,” he explains. “There’s a quality you’re gaining that you couldn’t necessarily prepare….It’s beyond your control.”

Elizabeth Anne Brown is an award-winning freelance journalist with bylines in top national magazines and newspapers. She’s based in Copenhagen, Denmark.