SciFri Extra: Picturing A Black Hole

The Event Horizon Telescope aims to take an image of a black hole. In this archival interview, astronomers describe the project’s methods and goals.

The Event Horizon Telescope is tackling one of the largest cosmological challenges ever undertaken: Take an image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, using a telescope the size of the Earth.

Now, the Event Horizon team has announced they have big news to share about those efforts. On Wednesday April 10th, it’s anticipated they will show a photo of the event horizon. Before they do, we wanted to share this 2016 conversation with Event Horizon project director Shep Doeleman and black hole expert Priya Natarajan, in which they discuss how you image an object as dark and elusive as a black hole.

These comments have been edited for clarity and length.

On seeing black holes.

Shep Doeleman: Black holes are by definition, something you can’t see. I like to imagine it as trying to take a picture of a dinosaur. We know dinosaurs exist. We see their footprints in clay. We see their bones, but no one’s ever seen one. And it’s the same with black holes.

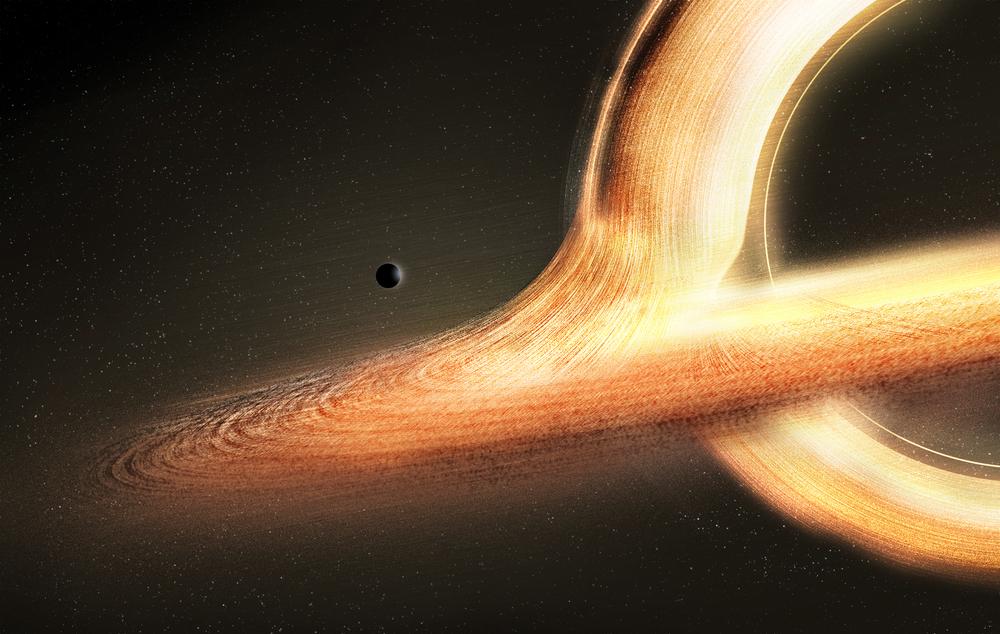

You can see light bend around them, but you can’t see them themselves. So you have to see find a way to build a telescope that has about 2,000 times the magnifying power of the Hubble Space Telescope, because these are the smallest things in the heavens that are predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity.

On the (tiny) size of black holes.

Shep Doeleman: They are the tiniest things you can imagine. They are the end result of gravity going haywire and collapsing a bunch of matter into a point source. But around that point is this wonderful membrane called the event horizon, and that’s the point where the gravity is so intense that even light can’t escape. So all this gas and dust around the black hole is madly trying to get into a very small volume. And in a cosmic traffic jam it heats up to billions of degrees. So black holes can be some of the brightest things that we see in the sky.

On what happens to matter after it crosses the event horizon.

Priyamvada Natarajan: Hawking had this interesting suggestion, which is, suppose you had an encyclopedia that was encased in a tight case. And you want to look up the capital of Rwanda. So you just go there. You look it up. You look at the page. Now you burn the encyclopedia. And all the ashes of the encyclopedia are still in that box. Nothing’s left of that book, right? It’s right in there.

So theoretically speaking, the information on the capital of Rwanda is still in there, it’s just that you don’t know how to access it and how to extract it any more. And I think that these are sort of the ways in which they’re starting to [think about] analogies for the event horizon to develop a quantum mechanical understanding, because that’s sort of what seems to be lacking.

On what we expect to see from the first image.

Shep Doeleman: As I like to say, it’s never a good idea to bet against Einstein. The idea is that, you should see this ring of light around the black hole. And the size and shape of that was predicted by Einstein. If we see some deviations from that, it doesn’t look round, if it’s not as large or it’s smaller than we think it should be, that would be an indication that either we’re not looking at a black hole—it could be something weird and exotic, like a boson star or something that would be very difficult to think about how we could even construct it. But it’s potentially possible. Or it would be, [as Priyamvada Natarajan has suggested], a change in general relativity—a change in Einstein’s equations.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.