#ObserveEverything…Including the Cat

In the book “Lost Cat,” two feline fans reveal how methodical observation and GPS technology helped solve a kitty mystery.

Over the past month, the SciFri Science Club has challenged you to #ObserveEverything. Methodical observation can be a key step in scientific discovery. In the case of Caroline Paul and Wendy MacNaughton, it also helped solve a feline mystery.

In 2009, author Caroline Paul was confined to bed, recovering from a serious accident, when her beloved cat Tibby ran away. With help from her girlfriend, illustrator Wendy MacNaughton, Paul staged an all-out effort at kitty rescue: She enlisted friends to stuff her neighbors’ mailboxes with fliers, visited the pound every three days, and plaintively called Tibby’s name out her back door each night. Finally, after five weeks, she figured Tibby was gone for good.

And then Tibby returned. “He came back, and he was fine, but also he had gotten fat,” MacNaughton recalls. “Caroline’s first response was ‘Yay!’ and then, ‘Where the hell have you been?’”

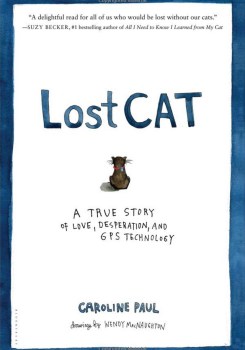

As Paul recalls in her book Lost Cat: A True Story of Love, Desperation, and GPS Technology (illustrated by MacNaughton), after he returned, Tibby stopped eating at home—the most obvious clue that he was continuing to visit a secret food source. With a bandaged head, arm, and reconstructed ankle, Paul knew she couldn’t follow Tibby to his “den of iniquity” (as she took to calling his secret hideout). But she thought GPS technology might do the trick.

“Operation Chasing Tibby” officially kicked off when Paul purchased the “Cat Track I,” a GPS unit specially manufactured for cats by a lone German inventor working in his garage. Only slightly bigger than a mini bar of Halloween chocolate, the Cat Track clipped directly onto Tibby’s collar. “When the cat came back, we had to take off the GPS, plug it in, and it would download a map that would show everywhere that Tibby had been” as a pink, computer-generated line, MacNaughton remembers.

Paul held out hope that the pink line would lead straight to Tibby’s hideout. Instead, what she got after a day’s worth of kitty roaming was this image, superimposed over a Google Maps snapshot of their neighborhood:

Instead of an orderly path, Paul saw a kindergartner’s pink crayon scribble. “I had no idea how to read this riot of feline footsteps,” she writes in Lost Cat. “Should I follow the lines that went westward across the street? Should I concentrate on the nucleus that seemed to stay within our block?” Twenty-two maps—recorded over 22 days—each showed a similarly confusing pink tangle.

Paul began to wonder if anomalies in the GPS readings were contaminating her data. She knew that satellite signals could bounce off tall buildings, alleyways, trees—even Tibby’s own chin. Abandoning the Cat Track, she and MacNaughton sought out what they hoped might be a more reliable method for making their observations. But a “Cat-Cam” attached to Tibby’s collar and programmed to snap a photo a minute produced only pictures of their yard, tabletop flower arrangements, and Tibby’s own whiskers. A cat video device proved even worse. “The video camera literally went from some shots and then to pure darkness as his chest hair covered up the lens,” Paul remembers.

Running out of alternatives, Paul and MacNaughton took a second look at their 22 GPS printouts. That’s when MacNaughton—with her artist’s eye—thought of a different approach to interpreting the Cat Track’s pink thicket of lines. First, MacNaughton used Photoshop to make each GPS map translucent. Then, she layered groups of four or six translucent maps (one map per day) on top of one another. Finally, she dropped a blue dot on the spots where the greatest number of pink lines overlapped. At the end of the process, MacNaughton and Paul had one master map, with dots corresponding to the areas Tibby had frequented most over time.

The meandering that Paul had compared to a riot of pink crayon suddenly made sense. Tibby had been repeatedly visiting a “suspicious area” a mere 10 houses away. In the end, a tip from a neighbor solved Paul and MacNaughton’s kitty mystery (which we won’t give away here).

Their tracking odyssey taught Paul and MacNaughton some valuable lessons about observation that apply to more than just tracing felines. For citizen scientists interested in “observing everything,” they have a few words of wisdom:

Tip number one, says Paul, is to be aware of your own biases. “I was really fast to dismiss things that, as a cat owner, I couldn’t believe [Tibby] would possibly do,” she admits. Rather than face the possibility that her cat of 13 years had ignored her repeated calls to return home, Paul decided he must be far, far away.

MacNaughton adds that data analysis need not be a solo endeavor. If you’re stuck, ask for help, and cast a wide net when searching for potential experts, she advises. For example, when Paul was stymied trying to figure out which pink lines were GPS anomalies and which were Tibby tracks, she reached out to Stanford University’s GPS lab. “That’s a fantastic thing to do,” MacNaughton says. “Absolutely reach out to the experts.”

And if Stanford doesn’t have the answer? “It might be a good idea to just talk to your neighbors and people who are looking at the same thing you’re looking at,” she says. “They might have some ideas, too”—perhaps even the final piece of the puzzle.

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.