‘Monster In A Barrel,’ And Other Haunting Ocean Drifters

Some predatory plankton appear innocent enough—until they go in for the kill.

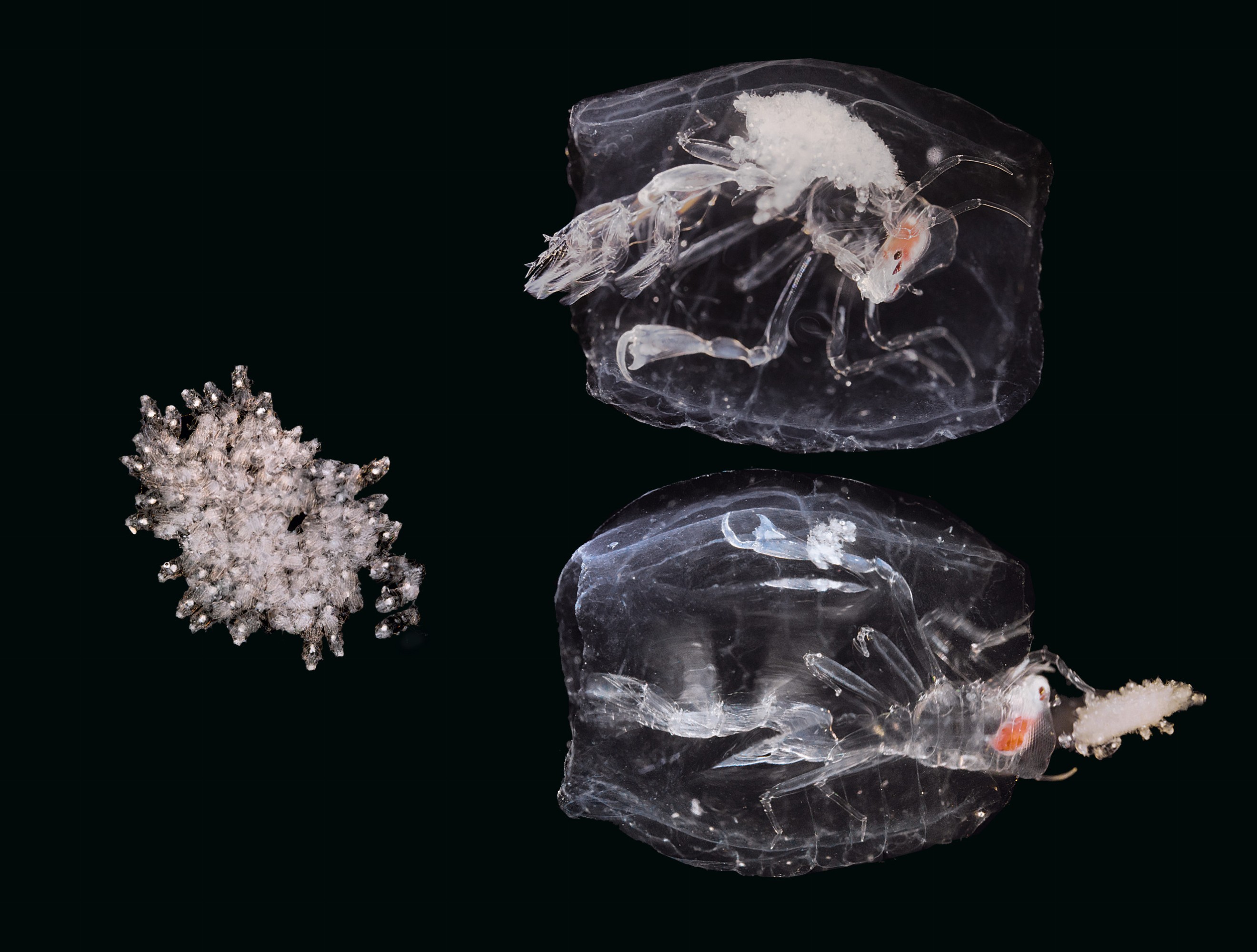

“Phronima sedentaria,” by Christian Sardet and Sarif Mirshak, CNRS. "P. sedentaria" has four compound eyes—and in this case, ruby-red retinas—that enable panoramic vision. Image courtesy of Tara Oceans, "Plankton: Wonders of the Drifting World"

In 1979, the cult classic sci-fi thriller Alien unleashed one of the most blood-chilling monsters in movie history. When it lurches from a dark spaceship vent (or a human chest), we feel Ripley’s fear.

The alien’s terrifying traits were inspired by an amalgam of sources, especially a type of parasitic wasp, according to Roger Luckhurst, author of a recent book about the flick. But there’s a striking physical resemblance between the extraterrestrial behemoth and another real-life organism mere millimeters in size: a transparent plankton species called Phronima sedentaria.* Coincidentally, the plankton’s carnivorous and parasitizing habits also parallel the alien’s.

Phronima sedentaria is a type of hyperiid amphipod, or small crustacean, that preys on gelatinous plankton, such as salps. The free-floating organism is equipped with claw-like appendages that slice open its victims, enabling the creature to crawl in and devour the soft tissues from the inside out. It then uses the leftover bits of the prey’s body to build a gelatinous protective home, or barrel, where females can deposit their young.

“[Phronima] has much more sophisticated behaviors than most crustaceans because it raises its young in a barrel, and it makes its barrels out of other creatures,” says Christian Sardet, the author and principal photographer of Plankton: Wonders of the Drifting World (University of Chicago Press, 2015), wherein he describes P. sedentaria as “a monster in a barrel.”

While Sardet, a cell and molecular biologist, has worked on other educational multimedia projects, including the film Exploring the Living Cell (2006), he’s best known for his work on the often-tiny organisms that drift with the current. His close friends and relatives refer to him as “Monsieur Plancton” and “Tonton Plancton” (Mr. Plankton and Uncle Plankton, respectively). “I don’t know,” laughs Sardet, who’s based in France. “They just made it up.”

Plankton: Wonders of the Drifting World (part of a larger project called Plankton Chronicles) abounds with pictures of more than 150 plankton species. Most of the photos were taken by Sardet when he was the research director of the French National Center for Scientific Research on the Villefranche-sur-mer Marine Station, as well as during a voyage on the Tara Oceans Expedition, an organization that studies climate and ecology out at sea.

“Having more people know about plankton was my main goal of the expedition,” Sardet says. “I was exposed to the different and beautiful behaviors of a lot of these organisms.”

“Over geologic time, the planktonic organisms have literally transformed the world as we know it,” says Mark Ohman, a biological oceanographer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, who wrote the prologue to the English edition of Sardet’s book. For instance, plankton oxygenated the ocean and atmosphere, making the world habitable for complex organisms. They also take in substantial amounts of carbon dioxide, created many of the oil and gas deposits in the ocean, and are fundamental to ocean food webs.

“It’s really a plankton-eat-plankton world out there,” says Ohman.

In the spirit of Halloween, here are a few other plankton species photographed by Sardet and colleagues. Their look and behavior, we think, could inspire the next big-screen monster.

*When asked if “Phronima sedentaria” was a model for the creature in “Alien,” Roger Luckhurst replied, “I hadn’t heard this story.” Some media sources, however, indicate that David Attenborough made the comparison in his Blue Planet series, noting that he compared “P. sedentaria” with the alien queen in the 1986 sequel, “Aliens.”

“A Medusa’s Feast,” by Christian Sardet, CNRS. Sardet was exploring Japan’s oceans when he spotted this scene of a juice-sucking jellyfish, Liriope tetraphylla, seizing a small fish in its proboscis. It took Sardet two hours to film this common species’ dining experience. Jellyfish are contact feeders. In these photos, the Liriope has captured a juvenile fish with one of its tentacles (a single tentacle can be studded with thousands of individual stinging cells called nemoatocysts). The Liriope then stretched its flexible mouth over the entire body, sucked the life from the fish, and spat out the dried corpse. Jellyfish are fierce predators, says Sardet. They can gobble up surprisingly large fish and crustaceans. Image courtesy of Tara Oceans, “Plankton: Wonders of the Drifting World.”

“Gymnosome.” Gymnosomes, more widely known as sea angels, were one of the first plankton to ever be described. Sea angels are shell-less snails that have a pair of fins that flutter like wings. “They are very graceful and beautiful,” says Sardet. But these angelic sea creatures have a mean bite (see below). Image courtesy of Tara Oceans

“A Gymnosome Devouring a Thecosome,” by Christian Sardet, CNRS. This gymnosome species, Pneumodermopsis paucidens, aggressively snags prey by extending a buccal cone. The buccal cone is somewhat like a tongue but with hardened, chitinous hooks that grasp parts of the prey, pulling it back towards the mouth and shredding it with the help of a rasp-like structure called a radula. Image courtesy of Tara Oceans, Plankton Chronicles

“Physalia, the Toxic Portuguese Man-of-War,” by Casey Dunn. Physalia is a kind of surface-floating siphonophore (an organism consisting of many smaller animals living in a colony in which members perform different functions) with alternating blue- and white-banded tentacles that can stretch down multiple feet into the ocean. These vibrant tentacles have a sting that’s dangerous to small fish and plankton, and injurious to humans. Mark Ohman remembers the large welts marring his skin after encountering a Physalia’s venom when he was swimming in the central tropical Pacific Ocean. “Physalia have a very virulent toxin,” he says. “In most cases, the attacks aren’t fatal, but there are some people that are hypersensitive to these particular toxins.” These plankton have a gas-filled float that allows them to bob just above the sea surface, making them appear like miniatures of the 18th-century Portuguese man-of-war vessels they’re named after. Certain members of the siphonophore are specialized for feeding, reproduction, flotation, and protection. Image courtesy of Brown University

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.