Meet The People Of Cassini

From a singing group to specially brewed beer, the Cassini family recounts what it was like working on the nearly 20-year mission.

This article is part of our special coverage of Cassini. Listen to one of the interviews Science Friday conducted with the Cassini team and marvel at the astounding images the orbiter took of Saturn and its moons. Plus, did you know the Cassini team has their own choir?

The early morning sky was still a shade of dark plum when Linda Spilker and her family staked out a viewing spot of the launch pad at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. The Cassini orbiter was prepared for its journey to Saturn. There were three prior attempts to launch, until at 4:43 a.m. EDT on Oct. 15, 1997, Cassini’s rocket started to slowly lift off the ground. As the rocket soared up into a cloud, it brightened and the crowd gasped.

The early morning sky was still a shade of dark plum when Linda Spilker and her family staked out a viewing spot of the launch pad at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. The Cassini orbiter was prepared for its journey to Saturn. There were three prior attempts to launch, until at 4:43 a.m. EDT on Oct. 15, 1997, Cassini’s rocket started to slowly lift off the ground. As the rocket soared up into a cloud, it brightened and the crowd gasped.

“People were wondering, ‘OK, did the rocket explode? What happened?’” recalls Spilker, Cassini’s project scientist who has worked on the mission since its inception in 1988. “Then a few seconds later, Cassini came out of the top of the cloud, and we were on our way to Saturn.”

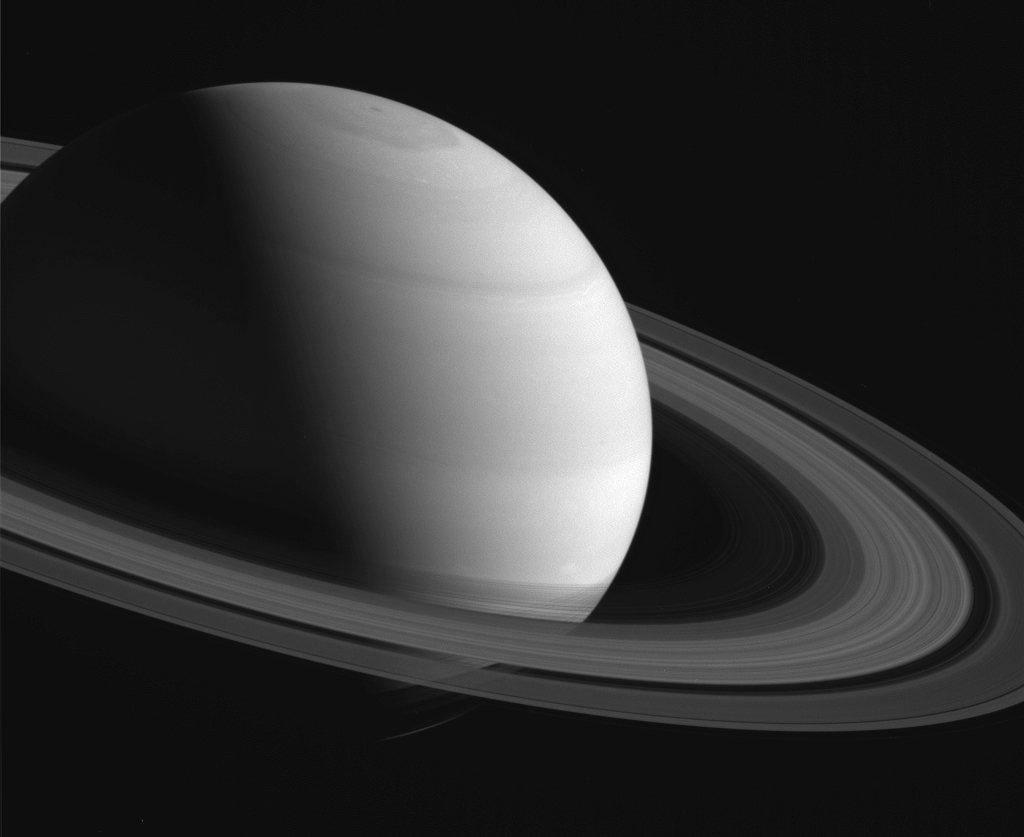

A view of Saturn from Cassini on March 19, 2016. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Like a sailing ship, Cassini cast off into the vast sea of space, Spilker says. The NASA spacecraft successfully entered Saturn’s orbit in 2004. Over the decades, it has beamed back hundreds of gigabytes of scientific data, captured stunning images, and provided strong hints that some of Saturn’s moons, like Titan and Enceladus, may have the potential to support life.

“It’s a beautiful, big robot,” Jeff Cuzzi, a scientist of rings and dust at NASA Ames Research Center, told Science Friday back in 2004 when Cassini first arrived at Saturn. “The hundreds of engineers here who have worked on this thing and made it function, and navigation and everything else—it’s terrific teamwork.”

On September 15, the nearly 20-year mission will come to a dramatic end. Planetary scientists, researchers, and engineers will bid farewell to Cassini as it plummets into Saturn—preventing Earth microbes from confusing any future search for life on the pristine moons. But the “beautiful, big robot” not only gave glimpses of our neighboring planets and explored uncharted pockets of our solar system; it created a family of scientists and engineers.

“It’s really a second family,” says Earl Maize, who started working on Cassini around 1992 and is now project manager for the mission. “We go out to eat together. A lot of time, we spend weekends and evenings together because of the asynchronous nature of operations.”

[The final year of the Cassini mission.]

At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, the Cassini members have gathered together for many “family” activities. They created a softball team, the Roving Marauders, pulled April Fools’ pranks on each other, and brewed special beers for milestones in Cassini’s life (“Earth Special Bitters” for the Earth swingby; “Saturn Pale Ale” for the Saturn orbit insertion). The team has even thrown big fests for Pi Day. Every year, Maize bakes a special Cassini-themed pumpkin pie.

“I make a little Saturn out of dough and put a little ring around it and plop that in the middle of the pumpkin [pie],” says Maize, who keeps a collection of empty beer bottles adorned with the special Cassini brew labels.

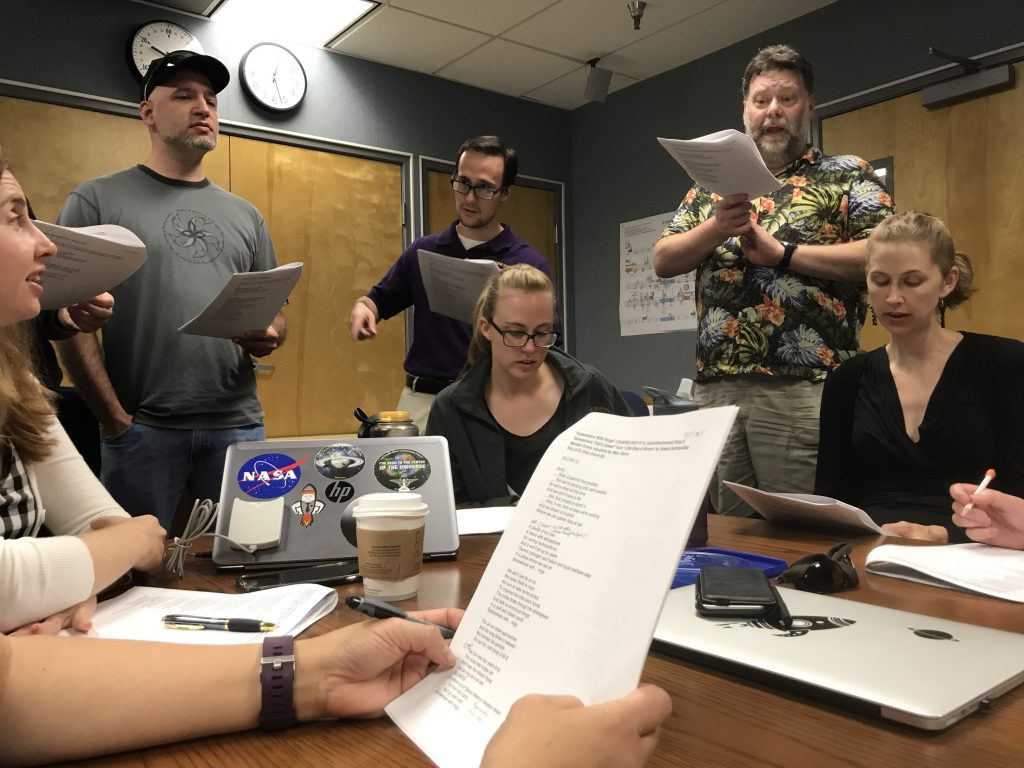

The Cassini team has gotten tight over the years. They even formed a group called the Cassini Virtual Singers. (It’s as cute as it sounds). pic.twitter.com/d82bk6JnBp

— Science Friday (@scifri) September 14, 2017

The Cassini family also formed a singing group in 1997, called the Cassini Virtual Singers, that perform parodies of popular songs at Pi Day, annual launch parties, and other special occasions. Each of the songs have a planetary twist. For instance, the song “Somewhere That’s Green” from the musical Little Shop Of Horrors has been adapted to “Somewhere With Rings.” The group is composed of everyone from software developers to engineers—all with varying levels of musical experience.

“We have some people who are absolutely fantastic musicians, and then we have people who have no singing ability. That would be me,” joked Trina Ray, a senior member of the technical staff on the Cassini mission at JPL.

Over long missions like Cassini, it’s common for the scientists to naturally grow close to each other. “There are many times when one of us will wave our hands, and the other one will say what we’re about to say,” says Maize.

In some cases, scientists’ children grow up together. Cassini is what Spilker calls a “multigenerational mission”—a project that was experienced by many of the team members’ children and real family members. Maize’s daughter grew up with Cassini and often visited JPL, while Spilker remembers bringing one of her daughters to the lab for a take your daughter to work day.

[Titan could have the right chemical conditions to create precursors to life.]

“We actually got the opportunity to put on these white jackets and caps and little booties, and go through the dust shower and we got our picture taken in front of the Cassini spacecraft as it was being built,” she says. “That was a very, very memorable moment.”

Members of the Cassini mission formed an intimate connection with the spacecraft, especially those who spent majority of their careers on the project. “I’m going to really miss this constant sort of burst of data from Cassini telling me something about Titan,” says Ray, who worked on Cassini for 21 years studying Titan.

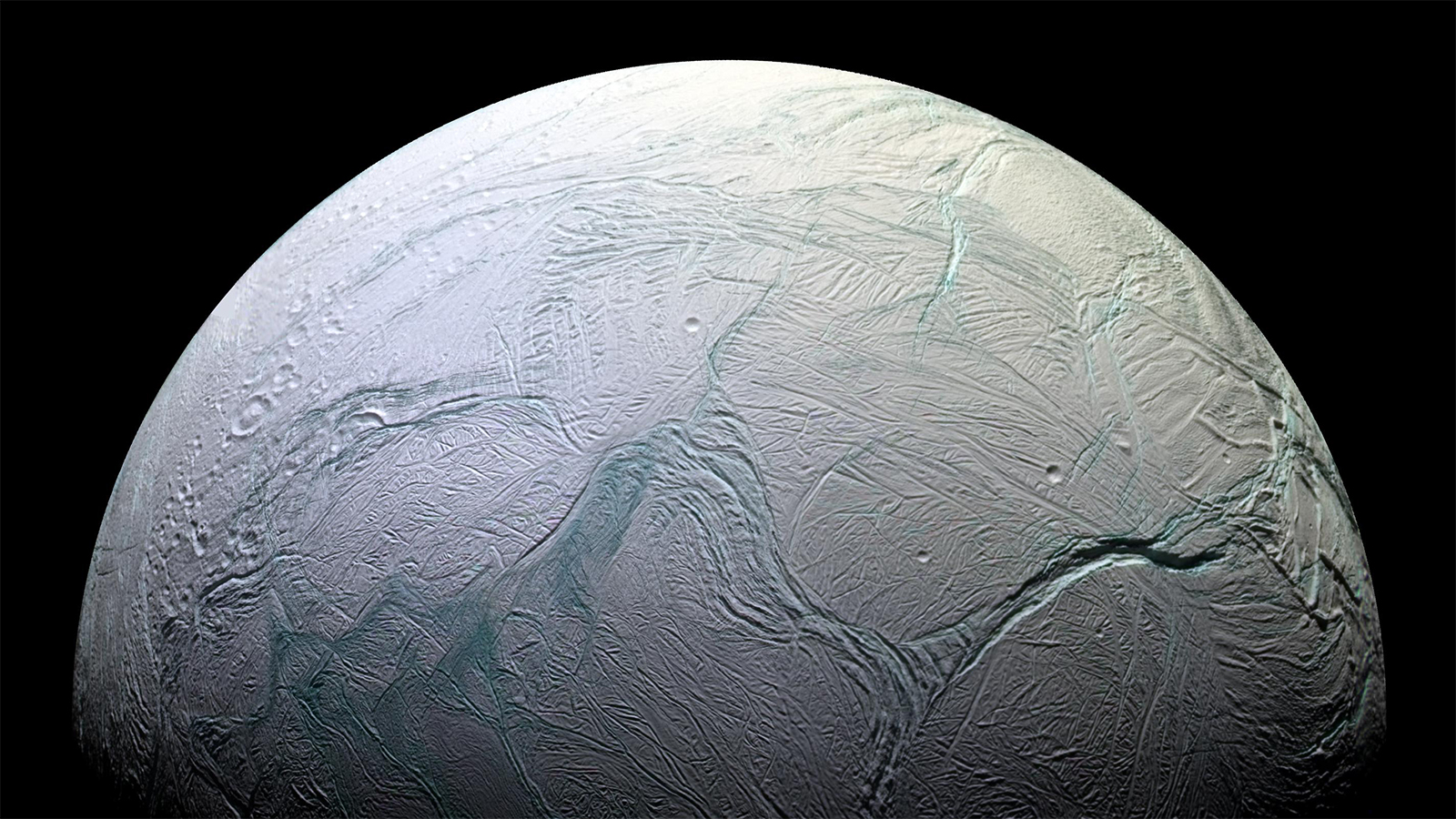

A colorized image of Enceladus' active south pole as viewed by the Cassini spacecraft on October 2008. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

The data analyzed from Cassini has had a profound impact on scientists’ understanding of Saturn and its moons. For example, in 2005, the spacecraft made a discovery about Enceladus—“the gem of the crown in the satellites of Saturn”—that had JPL planetary astronomer Bonnie Buratti reeling with excitement.

“We turned the instruments at Enceladus and took a very long exposure, and lo and behold we discovered active volcanoes,” she told SciFri in an interview on December 9, 2005. The plumes of ice particles spewing from these volcanoes contributes to the formation of Saturn’s second outermost ring, the E Ring, Buratti explained.

“The plumes on Enceladus are the greatest thing I’ve ever been involved in,” Buratti said.

[Enceladus becomes a top candidate for life.]

However, it may be years or even decades until a craft returns to the Saturn system for new data. There are currently proposals for future unmanned solar system exploration submitted to NASA’s New Frontiers program. While a Saturn probe is on the list, the destination has yet to be selected for the next mission.

“I don’t know when we’ll see a mission that’s that huge again,” Carolyn Porco, a planetary scientist and imaging team lead for the Cassini mission, told Science Friday in a recent interview. “It carried 12 instruments, and it also carried a probe that was deployed to enter the Titan atmosphere and land on its surface. That was landfall in the outer solar system. Cassini has accomplished so much, and we are about to bid that spacecraft goodbye.”

Some of the Cassini family have begun to transition to other missions, like the Europa Clipper, Mars 2020, and Juno missions, while others are planning on retirement. But for one last time, the Cassini scientists, engineers, and alumni will reunite for the orbiter’s final moments.

The Cassini alumni reunited for a group photo on June 21, 2017. Credit: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory-Caltech

Cassini’s fading signal will give scientists one last whisper of data before it disintegrates into Saturn’s atmosphere and becomes one with the planet it has so closely monitored. And the team of scientists who have worked intimately with Cassini will wait on bated breaths until the very end.

“It’s going to be a sad time,” says Spilker. However, Cassini leaves behind a legacy of planetary science discoveries and lifelong relationships.

“For Cassini, the final plunge is both an end and a beginning,” she says. “It’s kind of like a graduation. You have this group of people who have been together for a long time, and once you graduate—once the Cassini mission ends—everyone goes off onto new things.”

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.